CHAPTER ONE

The Role of Context in Children’s Learning from Objects and Experiences

Lynn D.Dierking

Institute for Learning Innovation

We went on a bus to the Glens of Antrim at Glenarrif (sic) forest park. Our guide was called Penny McBride. Penny took us for a walk and the first things we saw were phesants. We saw bamboo shoots. Then we went over a bridge and it was made of wood and log. Then we walked along the footpath. Then we saw the Redwood tree and it had a spongy bark. The tree came from America. [I]n America the Redwood is 300 feet tall. The redwood tree was 130 years old. Penny picked garlic leaves and let us smell them. Then we walked on the footpath and we saw a dead bird. Then we saw a squirrell (sic) going around a tree. We saw lots of beautiful waterfuls (sic). The water had foam and bubbles in it. There were platis bottle[s in] the water. We saw a wooden hut and the windows were all steamed up. We climbed up steep, steep hills and steps. Shaw dropped his money on the footpath. There were trunks there. We had our lunch at the picnic table. We tidied up the rubbish that was lying around. We went to the beach in Balleygalley. We played games like chasing Miss Armstrong a[nd] paddled in the water. We explored the rock pools. And we had a treasure hunt. At 3 o’clock we went home and we where (sic) very tired and happy. THE END.

—Sarah Jane Minford, seven-year-old Irish schoolgirl1

This actual post-field-trip account of a school trip to a nature center in Northern Ireland points out both the wonder and challenge of understanding children’s learning from objects and experiences. Clearly, this trip was memorable, and clearly objects and experiences played a tremendous role in making it so. Sarah’s rich descriptions of walking along a footpath; seeing pheasants, bamboo shoots, a bridge made of wood and log, a redwood tree, a dead bird, a squirrel, waterfalls, and a wooden hut; smelling garlic leaves; climbing hills and steps, eating a picnic lunch, playing games and exploring rock pools, all attest to the richness of this experience.2 At the same time, though, this rich account also demonstrates the challenges of understanding the meaning that children make of such objects and experiences, for how does one tease out the essential threads of learning from such a description? Did Sarah actually learn from this experience?

I argue that she did, but documenting this requires stepping back and thinking about learning from objects and experiences more broadly than is typically done; traditional models of learning, such as the transmission-absorption model (Hein, 1998; Hein & Alexander, 1998; Roschelle, 1995), do not account for or explain the highly interactive learning that results from such experiences and encounters with objects. An important missing ingredient is the role that context plays in facilitating learning from objects and experiences.

Traditional models of learning do not account for the richness and complexity of learning from objects and experiences, particularly not its rich contextual nature. Much of the traditional research has focused on learning in and from classrooms or laboratories, where much of the learning is decontextualized from direct experience with objects. The notion that objects and experience, with their inherent physical and sociocultural natures, might actually play an essential role in learning, and that these processes encompass much more than learning about facts and concepts but also include changes in attitudes, beliefs, aesthetic understandings, identity, etc., has been missing. Such models of learning do not work well when attempting to document the decontextualized learning in and from schools and laboratories; when these models are applied to the real object- and experience-centered world, they are seriously deficient.

This chapter describes a framework, the Contextual Model of Learning, that Falk and I have conceptualized to deal with the complexity and richness of learning and meaning-making from objects and experiences (Falk & Dierking, 2000). I then use the model to tease out and discuss some of the potential factors that might influence Sarah’s learning and meaning-making from her school trip to the forest park, utilizing research done by Falk and myself and others.

The Contextual Model of Learning starts from the premise that all learning is situated, a dialogue between the individual and his or her environment. It is not some abstract experience that can be isolated in a test tube or laboratory, but an organic, integrated experience that happens in the real world with real objects (Ceci & Roazzi, 1994; Lewin, 1951; Mead, 1934; Shweder, 1990). In other words, learning is a contextually driven effort to find meaning in the real world. The model advocates thinking more holistically about learning as a series of related and overlapping processes that accommodate the complexity and ephemeral nature of learning and meaning-making from objects and experiences, learning that we call free-choice learning.3

THE CONTEXTUAL MODEL OF LEARNING

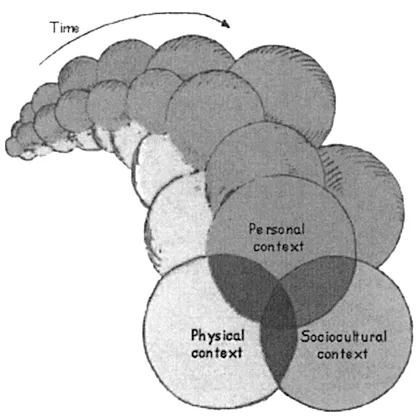

The Contextual Model of Learning (Falk & Dierking, 2000) grew out of a framework we developed 10 years ago that, at the time, we called the Interactive Experience Model (Falk & Dierking, 1992). In the last year we have built on and refined this model, recasting it as the Contextual Model of Learning. The Contextual Model suggests that three overlapping contexts contribute to and influence the interactions and experiences that children have with objects and the consequent learning and meaning-making—the personal context, the sociocultural context, and the physical context. Learning is the process/product of the interactions between these three contexts and is more descriptive than predictive. The power of the Contextual Model is not that it attempts to reduce complexity to one or two simple rules, but rather that it embraces and organizes complexity into a manageable and comprehensible whole.

The personal context refers to all that the learners bring to the learning situation, their interest and motivations, their preferences for learning modalities, their prior knowledge and experience. Four important lessons are at the heart of the personal context: (a) learning flows from appropriate motivational and emotional cues; (b) learning is facilitated by personal interest; (c) “new” knowledge is constructed from a foundation of prior experience and knowledge; and (d) learning is expressed within appropriate contexts.

The sociocultural context encompasses factors that recognize that learning is both an individual and a group experience. What someone learns, let alone why and how someone learns, is inextricably bound to the cultural and historical context in which that learning occurred. At one level, learning is distributed meaning-making. Knowledge, rather than being within the domain of the individual, is a shared process, and learning and meaning-making take place within often delimited communities of learners. In other words, there exist a myriad number of communities of learners, defined by the boundaries of shared knowledge and experience. Interestingly, not only is learning a sociocultural process in the here and now, but the historical and cultural modes of communicating ideas are also sociocultural in nature. This helps to account for the fact that universally, people respond well and better remember information if it is recounted to them in a story or narrative form, an ancient sociocultural vehicle for sharing information.

The third context, the physical context, accounts for the fact that learning does not occur isolated from the objects and experiences of the real world. The physical context includes the architecture and “feel” of the situation—in other words, the sights, sounds, and smells, as well as the design features of the experience. Our research and that of others suggests that when people are asked to recall their experiences in free-choice settings, like Glens of Antrim Forest Park, whether a day or two later or after 20 or 30 years, the most frequently recalled and persistent aspects relate to these physical context factors—memories of what an individual saw, what they did, and how they felt about those experiences.4

The model also includes a fourth and very important dimension—time. Looking at free-choice learning as a snapshot in time, even a long snapshot (e.g., the time Sarah spent exploring the forest park with her classmates and teacher) is woefully inadequate. One needs to pan the camera back in time and space so that one can see the learner across a larger swath of his or her life, and can view the experience within the larger context of the community and society in which he or she lives. A convenient, though admittedly artificial, way to think about this model is to consider learning as being constructed over time as people move through their sociocultural and physical worlds; over time, meaning is built up, layer upon layer. However, even this model does not quite capture the true dynamism of the process because even the layers themselves, once laid down, are not static or necessarily even permanent. All the layers, particularly those laid down earliest, interact and directly influence the shape and form of future layers; the learners both form and are formed by their environments. For convenience, we have distinguished three separate contexts, but it is important to keep in mind that these contexts are not really separate, or even separable.

FIG. 1.1. The Contextual Model of Learning. (Falk & Dierking, 2000).

Western science in general, and psychology in particular, are strongly tied to ideas of permanence—the brain is a constant, the environment is a given, memories are permanent. None of this appears to be, in fact, reality. None of the three contexts —personal, sociocultural, or physical—is ever stable or constant. Learning, as well as its constituent pieces, is ephemeral, always changing. Ultimately then, learning can be viewed as the never-ending integration and interaction of these three contexts over time. A valiant effort at depicting this model is shown in Fig. 1.1, appreciating that it really should be depicted in three dimensions and animated, so that both the temporal and interactive nature of learning could be captured.

The Contextual Model of Learning provides the large-scale framework within which to organize information about learning from objects and experience; the details vary depending on the specific context of the learner. After considering findings from hundreds of research studies, 10 key factors—or, more accurately, suites of factors —emerged as particularly fundamental to experiences with and from objects.5

Personal Context Factors

Motivation and Expectations. People have experiences with objects for many reasons and possess predetermined expectations for what those objects and experiences will hold. For example, children visiting a park like Glens of Antrim Forest Park expect to have a direct encounter with the outdoors, with plants and animals. These motivations and expectations directly affect what children do and what they learn from these objects and experiences. When expectations are fulfilled, learning is facilitated. When expectations are unmet, learning can suffer. Intrinsically motivated learners tend to be more successful learners than those who learn because they feel they have to. Learning situations are effective when they attract and reinforce intrinsically motivated individuals.

Interest. Based on prior interest, learners self-select what objects and experiences with which to interact, for example, what to see and do while exploring Glens of Antrim Forest Park. The term interest refers to a psychological construct that includes attention, persistence in a task, and continued curiosity, all important factors when one wants to understand what might motivate someone to become fully engaged and perhaps to learn something (Hidi, 1990). In research about free-choice learning, interest emerges as an important variable that greatly influences later learning (Dierking & Pollock, 1998; Falk & Dierking, 2000), directly affecting what people do and what they learn from objects and experiences such as encountered in a place like Glens of Antrim Forest Park. For this reason, learning is always highly personal.

Prior Knowledge and Experience. Prior knowledge and experience are fundamental factors contributing to learning (Roschelle, 1995). They play an important role in encounters that children have with objects and experiences in real world places like Glenarrif Forest Park. This prior knowledge and experience directly affects what children do and what they learn. The meaning that is made of objects and experiences is always framed within and constrained by prior knowledge and experience.

Choice and Control. Learning is facilitated when individuals can exercise choice over what and when they learn, and feel in control of their own learning. This is certainly the case for children. Real world settings, such as the outdoors, are quintessential free-choice learning settings and afford children abundant opportunity for both. Research suggests that children are very sensitive to these issues, often preferring to encounter objects in real-world settings with their families rather than with school groups for the very reason that they feel they have more choice and control over the experience (Griffin, 1998; Griffin & Dierking, 1999; Jensen, 1994). Consequently, effective learning situations afford learners abundant opportunity for both choice and control.

Sociocultural Context

Within-Group Sociocultural Mediation. Children are inherently social creatures. They learn and make meaning as part of social groups—groups with histories, groups that separately and collectively form communities of learners, such as Sarah’s class. Peers build social bonds through shared experiences and knowledge. All social groups in settings like Glens of Antrim Forest Park utilize each other as vehicles for deciphering information, for reinforcing shared beliefs, for making meaning. Such settings create unique milieus for such collaborative learning to occur. Children have experiences with objects with their peers and familiar adults, such as parents or teachers, and this collaborative learning greatly influences the meaning they make.

Facilitated Mediation by Others. Socially mediated learning does not only occur within one’s own social group. Powerful socially mediated learning occurs with other people perceived to be knowledgeable such as teachers, parents, and other facilitators. Such learning has long evolutionary and cultural antecedents. Interactions with other people can either enhance or inhibit a child’s object-based learning experience. When skillful, the staff of a free-choice learning setting can significantly facilitate visitor learning.

Physical Context Factors

Advance Preparation. Study after study has shown that people, particularly children, learn better when they feel secure in their surroundings and know what is expected of them, that is, when they have received advance organizers and orientation for the experience. Real-world settings, such as the outdoors, tend to be large, visually and aurally novel settings. When people feel disoriented, it directly affects their ability to focus on anything else; certainly this is the case for children. When people feel oriented, some novelty can enhance learning. Similarly, providing conceptual advance organizers significantly improves people’s ability to construct meaning from experiences. When children feel oriented and are provided conceptual advance organizers, this advance preparation enhances their object-based learning.

Setting. Whatever the learning experience, learning and meaningmaking are influenced by setting, that is, the ambiance, feel, and comfort of the place or situation. When children feel comfortable in a learning setting or situation, learning is enhanced. This is certainly important in real-world settings like the outdoors.

Design. Whatever the learning experience, learning and meaning-making are influenced by design, that is, the specific design elements of that experience. In real-world settings children see and experience authentic, real objects, within appropriate environments. Appropriately designed learning experiences that capitalize on the elements of the real world are compelling learning tools.

Subsequent Reinforcing Events and Experiences. Learning does not respect institutional boundaries. Children learn by accumulating understanding over time, from many sources in many different ways. Subsequent reinforcing events and experiences are as critical to learning from objects and experiences as are their immediate interactions. In a very real sense, the knowledge and experience gained from any one experience is incomplete; it requires enabling contexts to become whole. More often than not, these enabling contexts occur in other places—weeks, months, and often years later. These subsequent reinforcing events and experiences are as critical to learning from objects and experiences as are the initial encounters.

Individually and collectively, these 10 factors significantly contribute to the quality of a learning experience and inf luence the learning and meaning-making that results; thus, we can utilize this framework as a concrete model for understanding and facilitating children’s learning from objects and experiences. We can use Sarah’s experience at the forest park as a case study, to actually consider a very specific set of factors that might have influenced her learning from that experience.

SARAH’S EXPERIENCE

Clearly, personal context factors influenced her experience, evident as one reads Sarah’s account, written 2 weeks after the visit. Although this was a school trip with her teacher, Miss Armstrong, her very vivid description suggests she was highly motivated and interested and paid tremendous attention to details as the trip unfolded, remembering many of those details 2 weeks later. As I said earlier, I have visited this park myself and can attest to the accuracy of her description. Clearly, she and her classmates also had expectations for what the trip would hold. For example, Shaw had brought money along, perhaps to buy a special lunch or souvenir of the trip.

Sarah’s specific interests also are clear—she seemed most interested in all aspects of the natural world she was observing, in particular, the plants she encountered. She was able to describe in great detail her experience with a redwood tree, including the texture of its bark, ...