![]()

1

Protected Areas: Linking Environment and Well-being

Stolton Sue

Just offshore from Hiroshima, the island of Itsukushima in the Seto Inland Sea is one of the holiest places in Japan, a shrine to Shintoism since the 6th century. Today it is also recognized as a World Heritage site. Its huge, red-painted temple gate uniquely stands offshore in the shallow waters of the bay, making a famous backdrop to wedding photographs and, on the day we visit, a home for a couple of kites whose forked tails are clearly visible as they fly leisurely around the pillars. Magnificent though the temple is, we are actually as interested in the forests that cover the rest of the island. Virtually all of Japan’s lowland forests disappeared centuries ago under villages and rice paddies and today the only really old trees are found on land owned by the Buddhist and Shinto authorities. Being wooden, Japan’s temples need periodic renewal and so the sacred forests have been protected, sometimes for millennia, partly to provide the occasional piece of high quality timber. In the process, the authorities have created one of the earliest forms of protected area in the world, providing irreplaceable habitats for plants and animals that have disappeared elsewhere.

Sue Stolton

Linking People and Their Environment

Individual countries or communities have consciously managed the natural environment for millennia, but it was only after the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment recognized that ‘The protection and improvement of the human environment is a major issue which affects the well-being of peoples and economic development throughout the world’ that substantial global policies emerged linking natural assets to human existence (UN, 1972). Since then, the relationship between conservation and well-being has been a cause of much discussion and research, sparking a debate which intensified following the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

In the last 50 years humans have transformed the planet more radically than at any other point in our history. Extinction rates are thought to be a thousand times higher than expected under natural conditions (CBD, 2006). As we destroy and degrade entire ecosystems we also lose the benefits that these ecosystems provide. Vital goods and services like pure drinking water, fertile agricultural soils and medicinal plants all come from a healthy environment. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment estimates that around 60 per cent of the world’s ecosystem services (including 70 per cent of regulating and cultural services) are being degraded or used unsustainably (MEA, 2005).

The Role of Protected Areas

Protected areas aim to maintain the benefits provided by natural ecosystems, or in some cases long-established manipulated ecosystems, which cannot be replicated in intensively managed landscapes. Human societies have protected land and water from long before the start of recorded history – to protect grazing pasture, maintain timber supplies, stop avalanches, provide game for hunting or allow secure places for fish to breed. People have also protected places for less tangible reasons: because they were considered sacred or simply because they were recognized as aesthetically beautiful.

The modern concept of a ‘protected area’ – known variously as national park, wilderness area, game reserve, etc. – developed in the late 19th century as a response to rapid changes brought to lands in former European colonies and concern at the loss of ‘wilderness’. Protection was sometimes driven by a desire to stop species disappearing, as is the case with some of the colonially established parks in India, but also because colonizers were trying to retain remnants of the landscape that existed when they arrived. They often incorrectly assumed this to be in an untouched state, although in most cases ecology had been influenced by human activity for millennia. A handful of national parks in Africa, Asia and North America heralded a flood of protection that spread to Europe and Latin America and gathered momentum throughout the 20th century, and the number of protected areas continues to increase today. Most protected areas have been officially gazetted in the last 50 years – many even more recently – and the science and practice of management are both still at a relatively early stage.

The term ‘protected area’ embraces a wealth of variety, ranging from huge areas that show few signs of human influence to tiny culturally defined patches; and from areas so fragile that no visitation is allowed to living landscapes containing settled human communities. Although there are a growing number of protected areas near or within towns and cities, most are in rural areas. Early efforts often centred on preserving impressive landscapes, such as Yosemite National Park or the Grand Canyon in the US. More recently, recognition of extinction risk has switched the emphasis towards maintenance of species and ecosystems, and increasing efforts are made to identify new protected areas to fill ‘gaps’ in national conservation policies (Dudley and Parrish, 2006). The ecological repercussions of climate change are adding urgency to attempts to conserve what we can of the planet’s diversity.

The earliest protected areas were generally imposed on the original inhabitants by the colonial powers, in much the same way that the rest of the land and water was divided up, and communities were often forcibly relocated from land that had in some cases been their traditional homelands for centuries. The practice of ‘top-down’ decision-making about protection carried on in many newly independent states in the tropics. Today, efforts by human-rights lobbyists and leadership from the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), set up following the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, are gradually resulting in greater democratic controls on the selection and agreement of protected areas, although the net costs and benefits are often still not evenly distributed.

Costs and Benefits of Protected Areas

Protected areas are the cornerstones of national and international conservation strategies. They act as refuges for species and ecological processes and provide space for natural evolution and future ecological restoration, for example, by maintaining species until management elsewhere is modified to allow their existence in the wider landscape or seascape.

Today protected areas are increasingly also expected to deliver a wide range of social and economic benefits. Assurances that protected areas will provide such benefits are often crucial to attracting the support needed for their creation, but delivering on these promises is seldom easy. In some cases it may mean broadening the scope of benefits delivered without undermining what protected areas were set up for in the first place, which is no simple task. However, if we do not understand and publicize the full range of benefits from protected areas we risk not only reducing the chances of new protected areas being established but even of seeing some existing protected areas being degazetted and their values lost.

It has been estimated that the cost of buying all of the world’s biodiversity hotspots (i.e. the parts of the world with the highest diversity of plants and animals) outright is around US$100 billion – the equivalent of less than five years’ expenditure on soft drinks in the US (Buckley, 2009). We are not suggesting this strategy but such comparisons help put conservation in context. In parallel with the problem that much important biodiversity remains unprotected, many areas that are protected are underfunded, poorly managed and, as a result, losing values. It has been estimated that the world spends around US$6.5 billion (2000 values) each year on the management of the existing protected area network; an amount considered to be woefully inadequate. To manage the existing terrestrial protected areas effectively, about 11 per cent of total land area, and expand the network to about 15 per cent of land area (bearing in mind the expanded network required by the CBD) has been estimated to require between US$20 and US$28 billion annually. In addition adequately protected marine reserves, covering some 30 per cent of total area, would cost at most around US$23 billion per year in recurrent costs, plus some US$6 billion per year (over 30 years) in start-up costs (Balmford et al., 2002).

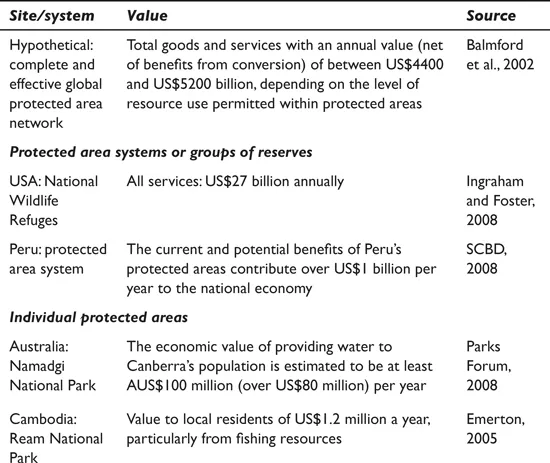

Although these figures seem immense at first sight, the role protected areas play in providing us with multiple benefits should be an argument that this type of investment is necessary. As shown in Table 1.1, there are beginning to be attempts to work out the economic value of protected areas. Although different methodologies are used and different benefits valued in the table (the complexities of valuation are noted, but not discussed here), the indication is that the benefits of protection are likely to far outweigh the costs.

Table 1.1 Protected area economic values

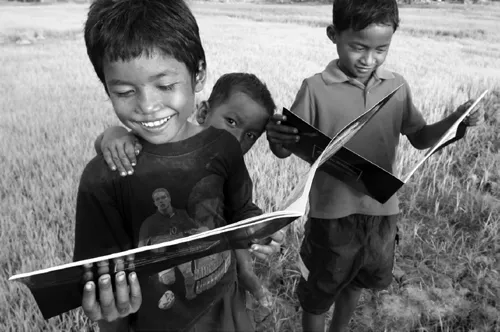

Figure 1.1 Three Khmer boys reading a book on fish conservation on the banks of the Tonle Sap River, Cambodia

Source: © WWF-Canon/Zeb Hogan

Making the Case for Protected Areas

This book is based on the premise that ethical or emotional arguments about saving biodiversity are not enough to persuade governments or communities of the necessity to set aside large areas – or large enough areas – of land and water from development in perpetuity. To maintain and, where necessary, expand the protected area network we need to demonstrate its wider uses and appeal. Further, it is generally not enough to simply show that these values exist; they need to stack up economically and socially as well.

We take this approach with some caution. Sceptics argue that too much emphasis on ecosystem services and market-based conservation is a risky strategy, because if these do not prove to be as important as we hope, then we have lost the justification for protection (e.g. McCauley, 2006). We recognize these risks, but at the same time we believe that the risks of pinning all the hopes of conservation’s most powerful tool on a fashion for saving wild species are even greater.

Conservation organizations tend to celebrate the creation of a protected area as a permanent victory for ‘nature’. Over the past few years, between the two of us we have spoken to senior officials in eight different countries who have said openly that they regard their protected area designations as temporary and the list of degazetted protected areas continues to grow. The stimulus for the book, and the associated WWF Arguments for Protection project, is a conviction that we have a relatively brief window of opportunity to persuade governments and the public that commitments to protected areas, often made hurriedly to satisfy donors or even cynically to tie-up land that can be exploited later, have real value and are worth committing to and supporting over time.

This book thus aims to demonstrate that protected areas have a wide range of values, not always only economic, which provide a string of practical, cultural and spiritual benefits that cannot easily be met through other means. We are convinced that to identify, manage and promote these benefits is vital for the continued survival of protected areas.

We should mention an important caveat; not all protected areas will provide every kind of value. Failure to provide multiple benefits is not a sign that the protected area is a failure and, for example, an overemphasis on social values may detract from the primary reason that society sets aside protected areas. However, the underlying concept of multiple values remains extremely powerful.

Defining Protected Areas

IUCN defines a protected area as: ‘A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.’ (Dudley, 2008) The primary aim is to achieve the long-term conservation of nature, but achievement of this goal brings with it many associated ecosystem services and cultural values.

Protected areas exist under literally dozens of names and management models. To provide some structure, IUCN has agreed a set of six categories for protected areas, based on management objectives (Dudley, 2008). Like all artificial definitions these are imprecise and the distinction between them sometimes blurred, but they provide a succinct overview of the multiplicity of protected area types:

- Category I: strict protection (Ia Strict Nature Reserve and Ib Wilderness Area);

- Category II: ecosystem conservation and recreation (National Park);

- Category III: conservation of natural features (Natural Monument or Feature);

- Category IV: conservation of habitats and species (Habitat/Species Management Area);

- Category V: landscape/seascape conservation and recreation (Protected Landscape/Seascape);

- Category VI: sustainable use of natural resources (Protected Area with Sustainable Use of Natural Resources).

It would be fair to say that the precise boundaries of what is permitted inside a protected area are still being debated. Many older protected areas, which originally excluded people, have relaxed their rules in the face of protests or because managers recognized that the restrictions were unnecessary: Nyika National Park in Malawi, for example, once again permits local communities access to four traditional sacred sites for raindance ceremonies. The balance between use and protection, various trade-offs and the long-term maintenance of a protected area’s values are seldom fixed at the time of the first management plan but rather evolve over years. It is a sensitive subject, with some NGOs reacting strongly against attempts to ‘open up’ protected areas and others arguin...