![]()

1

Introduction—Bienvenidos

Berta Rosa Berriz, Amanda Claudia Wager and Vivian Maria Poey

Figure 1.1 Playing with Friends

“My friends here and at home are good. Some of them speak English, some Spanish and some both. Some of us like to play the same things. Some of us are all Puerto Rican and Americans.”

—Third grader in Berta’s doctoral dissertation: The Emergent Cultural Identity of Puerto Rican and Dominican Third-grade Students and Its Relation to Academic Performance

—( Berriz, 2005)

The picture in Figure 1.1 is but one example of how we, the three editors, and the many inspirational contributors to this volume have connected to students’ funds of knowledge while utilizing the arts for language learning with emergent bilingual (EB) students, families, and communities (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2006). Knowing who our emergent bilingual students are and honoring their voices is essential to the development of their academic identities. In this introductory chapter, we begin by introducing ourselves, so that you immediately know our positionalities—who we are and the lens we see the world through—to make visible why this work is so close to our hearts. We proceed by contextualizing the work with demographic information regarding emergent bilingual learners, followed by the theoretical foundations and connections among the three disciplines represented: the arts, literacies, and language acquisition. Along the way, we provide rich examples from within this volume, using the arts as a way of talking, and conclude with an invitation to read onwards as we briefly describe the heart of each chapter within Art as a Way of Talking.

Our Journeys: Multilingual Students, Artists, Activists, Teachers, Researchers, and Scholars

The three of us—Berta, Vivian, and Amanda—come from distinct walks of life, with overlaps and similarities. We have been teachers, specializing in one of the three areas of arts, literacies, and language acquisition; however, we view these distinct areas as interwoven within the education of emergent bilingual learners. We continually seek to further educate ourselves, each other, and reach out to a broader community in these realms. This drive led us to form our collaborative and to seek out other voices in the field. In order to understand the lens that we bring to this text, we provide our histories and lived experiences as an entry point.

Berta’s Story

Recently, as I searched for documents of our move to the United States, I came across this poem stitching my identity in my passion for dance, the land I left behind, as well as the constant presence of mi Abuelita, America. Abuelita is my spirit guide as I move through new contexts, challenges, and landscapes. I wrote this poem as a dancer taking a leap into the world of public education. In my view, artists were the original teachers. We are the ones who observed nature (scientists) and created ritual celebrations (philosophers). Artists documented everyday life experiences in drawings, stories, song, and costumes (historians). Storytellers captured traditions, values, advice, and humor and passed them on to communities (healers).

a dancer

all that she could

bring to the night

dance

was a dress

she stitched

for time

in preparation

carefully

in again out

with her

Grandmother’s own needle

she stitched

appliqués

of people

rich red

brown earth

under their feet

their skin

next to sun blue air

working

tending to one another

familia

hermana

compadre

on silk she painted

creatures weaving

days and nights

spiders

humming birds

star fish

alacrán

the earth life weave

bonded with the heavens

rivers flowing

marshes sucking moisture

fish flipping

in the nets

gathering

flechas

lanzas

machetes

maracas

marimba

tambor

renewing in the weapons

her own firmness

reliving the soft song

reworking the tools

massing seeds

pounding the dough

casabe

enmeshed

in a thick

knotted border

a tight thread

encircled

still spinning

flaring

to meet the night dance

I still have my Abuelita’s needles.

I moved to this country from Cuba at the age of eight. As a third grader, I was compelled to give up my country, my language, and my name. In many ways, I am my students; I have felt their confusion, embarrassment, and anger firsthand. I understand how the imposition of a new language and culture can profoundly affect the process of identity-formation, self-esteem, and the capacity for learning of a young child. My immigration story motivates my activism as an artist and educator. My journey as a bilingual teacher has included dual language and native language literacy settings, including African American students as well as Latinx students in transitional bilingual and special education programs in severely segregated public school contexts. Critical awareness of socio-structural impositions and limitations placed on my students required that I discard standardized curriculum in favor of engaging my learning community in a critical analysis of their own potential to excel and make their mark in a changing world. My teaching experience necessitated a deeper look at the relationship between my students’ identities and their academic progress.

Stepping out of my classroom into the world of research at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, I searched for answers regarding the persistent racial and ethnic disparities among third-grade students’ academic achievement (BPS Office of Assessment and Evaluation, 2003). I was both lifted and led by pioneers in the anthropology of education, George Spindler and Carola Suárez-Orozco, who focus on the psycho-social impact of immigration on those called “other” in school (Suárez-Orozco, 2004). Children’s drawings centered interviews exploring the relationship between the cultural identity and academic performance of these emergent bilingual youth. Voices from my doctoral studies at Harvard stay with me. Families are the foundation of a sense of belonging for my students that define their engagement with mainstream society. As Pedro, a third grader in my study put it, “family is part of the heart.” Language is an important part of staying close to family. Toña, another student, visited her grandmother in the Dominican Republic and spoke to her in Spanish, “I love it there.” Pedro describes how he thinks about language, “Yo le hablo en inglés a mis amigos y a los que no saben inglés, yo le hablo en español.” (I speak English with my friends and I speak Spanish with those who do not speak English). Pedro also gives us insight to the importance of Spanish in his life. “We speak Spanish because in my family, my parents do not speak English. My mom wants me to speak Spanish and it feels good to speak Spanish” (Berriz, 2005).

Keeping this history close to heart, my hope for Art as a Way of Talking is to empower teachers, families, and communities with a guide for subverting the limit situations, which are barriers imposed on the oppressed that prevent them from being humanized and that can be effectively eliminated by using an arts-based problem posing method of education (Freire, 1970). The arts encourage our emergent bilingual scholars to use their imaginations as a way of linking their lived experiences to solve academic problems (Brice-Heath & Roach, 1999). It is our intention that Art as a Way of Talking broadens possibilities for young scholars of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Vivian: an Artist’s Journey Through her Family History

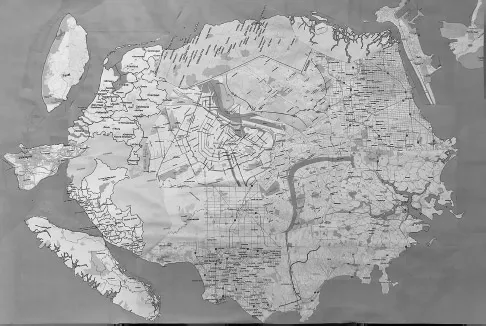

As Berta describes earlier, history shapes who we are. Nearly every generation, as far as I can trace in my father’s family, has spent time in exile. This image (Figure 1.2) represents my grandfather’s trajectory. He was born in Tampa in 1900 as my great-grandfather was in exile during the Cuban War of Independence (known in the US as the Spanish American War). The faint pencil lines show his trajectory from his birth in Tampa to Havana followed by his exile in Mexico City and finally Miami, Florida, where he settled until his death. I have included this as part of my own history by layering an image of my feet in the ocean at Varadero, Cuba—a place described in family stories as a paradise where “la arena es como el azúcar y el agua tan transparente que puedes ver hasta la mugre de las uñas” (the sand is like sugar and the water so clear that you can see the dirt under your nails).

I was 14 and in ninth grade when I moved to the United States. Before moving to Miami, I had lived in three different countries, sang three national anthems, and learned three different versions of history with varying historical figures and geographic regions. Everything I knew seemed irrelevant to my education in this country. It was not until I took a photography class in community college that I began to understand that my own experience was relevant, and that I could explore and share it though my artwork. While looking at contemporary photographers I began to feel connected. I was inspired by the work of Latin American artists, such as Graciela Iturbide and Manuel Alvarez Bravo, to look deeper into my own experiences and further my learning—not just about photography but about everything. Photography provided both a thirst for knowledge and a language to make meaning of the world. Later, I began to connect with the work of other artists, such as Fred Wilson, who created an alternate historical narrative by reorganizing and re-presenting the collection of the Maryland Historical Museum; Mary Beth Meehan, who photographed the bedrooms of immigrants, bringing an intimate view of a silent community; and Gustavo Perez Firmat, whose bilingual poetry says more than even two languages can speak.

Figure 1.2 Aguirre exile 1898

Through my work I have been investigating my family history and its place in the larger history of Cuba, tracking my father’s family history and creating a visual biography of past generations, leading up to my daughter who is a trace, a document, of Cuban, Haitian, and American history (www.lesley.edu/stories/vivian-poey). This work led me to do historical research, to read news archives, and to unearth family stories. Trying to connect to and represent places that are far away and stories that happened long ago, I researched maps during the time of my ancestors. I went back as far as the 1700s when my great-great-great-grandfather moved from France to Cuba. Creating these photographs forced me to connect to the details of my ancestor’s lives. The times and places became real and alive, and the stories I learned made visible how those who came before me shaped my present context. These stories, both extraordinary and in some ways shameful, create personal connections across time and space that resonate in ways that are still relevant today.

I have been working in this historical research vein since my graduate thesis On Fictional Ground and Culinary Maps (https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/jppp/vol2/iss3/5/), where I investigated the intertwined ideas of authenticity and assimilation. Working through the arts with these ideas about investigating and communicating our worlds translated into invaluable learning about my own students. As a photography mentor with teens from every public high school in Pittsburgh and later as an artist teacher in Washington DC with a young student body representing multiple countries from Africa and Latin America, I listened to my students’ voices as they developed eloquent multimodal artwork that spoke to the personal and academic alike.

Amanda: Playing with Languages and Places

Connecting to Vivian’s use of maps to tell her history, my “Life Map” collage (Figure 1.3) is the accumulation of the many different places I have lived; reflecting the space of displacement—of neither being here nor there, from this place or that place—that I often feel. My family history, through various moves and displaced moments in time, has made me adapt to new locations and languages quickly. Being a White, cisgender able-bodied English-speaking woman from the middle class, I come to this space of displacement with a great deal of privilege.

My name is Amanda Claudia Wager. My late father is Peter Polland Wager of Chicago and my mother is Marilyn Dee Pincus of Los Angeles. Both sides of my biological family stem from Jewish Ashkenazi ancestry. In the beginning of the 20th century, my great-grandparents came to the United States from Poland/Russia—the borders were constantly shifting—fleeing the Jewish genocide of the Russian Red Army. My grandparents spoke English and Yiddish, and we spoke English and eventually Dutch in our house. My stepfather Paul Logchies, from Amsterdam in the Netherlands, raised me from age 12 onwards. Growing up in Amsterdam, a small global city surrounded by countries that speak many other languages, we learned and heard languages everywhere. We played with languages by moving in and out of one on to another. Language learning and teaching was an art form in itself and has led me to where I am now, with a passion for teaching languages and literacies via the arts.

Figure 1.3 Amanda Life Map

Growing up in Los Angeles, I learned Spanish in school and I was often surrounded by it in friend’s homes and on the streets. When I was 5 years old my family moved to London for a year, where I was told my first day of school to “Queue ...