![]()

IV

Developing a Protocol

![]()

Chapter 10

The “Nonfiction Photographic Environment”

A Range of Implied Authenticity

The integrity of each photo is critical. You can’t compromise one without raising a question about all.

—Alex MacLeod, The Seattle Times1

The digital age presents us with challenges at once profound and exhilarating. How can we apply limitless image-processing technologies in creative and commercial ways—without fracturing the credibility that is the foundation of our profession? Is it even possible? Or will we Photoshop ourselves out of a job? In a media environment awash in false yet photorealistic imagery, can journalists maintain a fortress of credibility around real images, isolating them in the public mind from “photo-illustrations” and other contrivances?

Part III examined principles of journalistic ethics, as well as the conventions of taking, processing, and publishing photographs. We can now draw upon those traditions in formulating guidelines for the responsible, credibility-preserving implementation of digital image processing. Part IV, the essence of this book, is intended to sharpen our focus and to assist in protocol development, not by providing all the answers but by proposing a method of asking questions:

• First, this chapter outlines the nonfiction photographic environment, a category broader than “photojournalism” or “hard news,” and one that embraces a range of implied authenticity.

• The following chapters offer various tests that reveal whether a photo meets the reader’s “Qualified Expectation of Reality,” or “QER,” offered here as the essential standard for identifying “photofiction.”

• The text goes on to address appropriate disclosure of photofiction, and the implications of “cosmetic” retouching.

• Chapter 18 explains how to apply the guidelines in a brief list of questions and steps, and the book concludes with an exploration of the future of journalistic photography in Chapters 19 and 20.

Taken together, these chapters offer an approach to assessing the ethics of an altered mass-media photograph. At every step, choices must be made and judgments rendered. Where students or professionals draw the line will depend upon their own perceptions of their responsibilities.

RE-CATEGORIZING IMAGES

It is an uncertain environment of ubiquitous image manipulation, diminished faith in mass media, and justifiable viewer skepticism that visual journalists face as they attempt to preserve their credibility. How can they do it? One preliminary step is to better define the category of mass-media images that carry implications of authenticity. This chapter argues that photocredi-bility’s survival requires applying ethical standards to a category broader than “photojournalism” or “hard news.”2

This chapter also suggests that for ethical purposes, distinctions between newspapers, magazines, and other media have begun to outlive their usefulness. In an age in which the forms and structures of nonfiction communication diverge and recombine into innumerable permutations, why should ethical guidelines turn on details such as paper stock, binding methods, or publication frequency? It makes more sense to examine a medium’s substance, its context, and especially its implications of veracity.

FIRST OF ALL, WHAT IS A PHOTOGRAPH?

As quoted in Chapter 3, one professional said: “I don’t consider a photograph to be a photograph anymore. It’s something to work with.” Indeed, once a photo’s elements have been fragmented, recolored, repositioned, and combined with elements from other photos or even other media altogether, is it still a “photograph”?

Here, the short answer is yes. If a published image is photo-based, looks like a photo, and contains no clear visual clues that it has been manipulated (recast as a photo-montage, for example), we will treat it as a photograph if for no other reason than the public is likely to do the same; in fact, we will treat it as a photograph for precisely that reason. (Note: In its photography alteration protocol, National Geographic defines photography as “any image captured through the use of an optical lens device and stored on any chemical, optical or electronic media.”)

PHOTOJOURNALISM: EYEWITNESS TO HISTORY

No one argues that journalistic principles should apply to visual fiction invented for comic or fantastic effect. After all, readers do not expect the same correspondence to reality from an image of a 200-foot-tall beer bottle in a magazine advertisement and a front-page photo in The Washington Post. But what about the vast middle ground in between these extremes? How do we sort out tricky questions such as whether identical standards should apply to news magazines versus general interest magazines; “features” versus “articles”; magazine covers versus interior photos; or print versus online media?

Let us start with the kind of photography for which we might expect the strictest standards of all: photojournalism. Conventional definitions of “photojournalism,” like those of journalism itself, are typically tied to the dissemination of news. The word often evokes the kind of photography enshrined for decades in National Geographic and Life. It is thought to provide a window on the world, an “eyewitness to history,” as Peter Arnett wrote in Flash! The Associated Press Covers the World?3 In the public mind, photojournalism is slice-of-life documentation, charged with a you-are-there immediacy and weighty with journalistic authority. In short, it is serious business.

Arnett asserts that “one of the stanchions of American democracy” is the notion that photojournalism provides viewers with “a firm basis of facts by which to form their own judgment.” He adds, “If democracy is the voice of the people, then the AP is its stenographer.” This stenographic or reporto-rial aspect of Associated Press photographers and other professionals is at the heart of our notions of photojournalism. We admire its practitioners for their competence, their persistence, their recognition of what is compelling or newsworthy, and sometimes their bravery. Their work may shed new light on a subject, or change our perceptions of society or nature. It may even rise to the level of art, but in any case it does not mislead. Photojour-nalistic images may be harrowing or soothing, extraordinary or mundane, artful or appalling, but above all they are, in a word, real.

Let us not dwell on the philosophical question of the ages: What is real? As we saw in Chapter 1, private citizens and media professionals alike regularly use the words “real” and “reality” in drawing ethical distinctions in visual media. Throughout this book we explore photography’s objectivity, or lack of it. For now, let us simply acknowledge that photojournalism, as its name makes obvious, is a kind of journalism.

DO WE STILL KNOW WHAT JOURNALISM IS?

The problem is that “journalism” itself is so vaguely defined. If anything, its parameters are blurrier than ever, given the news media’s adoption of entertainment values, the much-discussed convergence of media technologies, and the blending of previously discrete practices or disciplines. One example:The New York Times in 1998 referred to “one of the hottest fashions in the media industry: the melding of journalism and Hollywood.”4 Several major magazines have sold stories to movie makers. For example, Vanity Fair writer Marie Brenner’s article on a tobacco industry whistle blower was optioned by Disney. Brenner admitted that the Hollywood connection might affect content: “Are you doing an article because it might sell, or because it is journalistically sound?”5

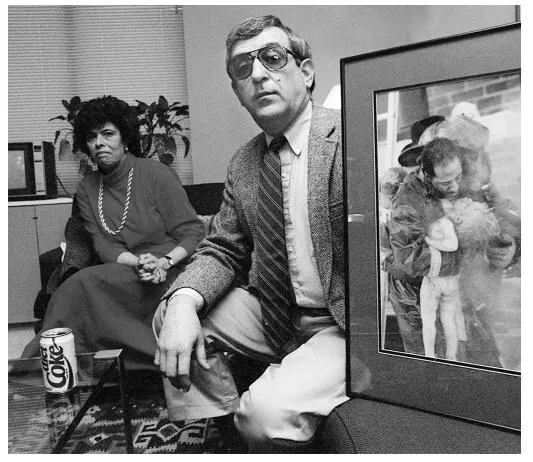

FIGURE 10.1 More than a decade after the St. Louis Post-Dispatch removed a soda can from this news photo, professionals still debate the ethics of the decision. Says the paper’s Larry Coyne: “It was a mistake; it would never happen here again.”

Another vague distinction is the line between drama and documentary. The ostensibly nonfiction television programs 20/20, Unsolved Mysteries, America’s Most Wanted, Saturday Evening with Connie Chung, and A Current Affair have all mixed actual news footage with staged re-enactments.6

To appreciate how many barriers have been breached, consider all the hybrid terms and concepts entering the lexicon in recent years: advertorial, infomercial, infotainment, docudrama, net ‘zines, “reality-based” entertainment, “magazine”-format television shows...