This is a test

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

There are many challenges facing educators in the field of sustainability. This text aims to analyze the state of the art in teaching business sustainability worldwide, and what teaching practices and tools are achieving successful results.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Teaching Business Sustainability by Chris Galea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part 1

Theory, critique and ideas

1

Mental models @ work

Implications for teaching sustainability

John Adams

Saybrook Graduate School, USA

Saybrook Graduate School, USA

1.1 Background: what we say and what we do

Human activity during the second half of the 20th century produced huge challenges that are only now becoming evident to significant numbers of people. The engines driving gains in wealth, technology and the production of goods are using up ever-increasing amounts of non-renewable resources and generating unprecedented amounts of waste. New diseases more complex than any encountered before have appeared and have spread globally. Unprecedented numbers of people are left out of the positive advances of 'Western science' and are living in abject poverty—creating a skewed distribution of a few 'haves' and a majority of 'have nots'. The population of the planet has tripled in the past 50 years, and more than half of the people who have ever lived are alive today.

A higher proportion of the population is involved in warfare (civil and ethnic wars are just as deadly as the global kind) now than at any other time in history. As a result of population pressures, growing aspirations and local warfare, unprecedented numbers of people are migrating to the less densely populated countries of the world. Grain and fish production both peaked in the 1980s and have been level or declining ever since. Meat consumption has become a symbol of affluence, and its production makes huge demands on grain harvests and water supplies. Arable lands are turning into deserts, and aquifers are becoming salty as we try to feed the global population.

Since the 1990s, significant attention has been devoted to what it will take to address conditions such as these and to bequeath a high-quality and equitable future to succeeding generations. Ecologists, economists, population experts, business leaders, academics, psychologists and spiritual leaders have all weighed in with their suggestions. Most predict a less than rosy future if we do not make significant changes quickly; some say it is already too late.

Now we have entered a new century, and so far there is no indication that any of these problems has abated. In fact, some of the trends (e.g. emission of greenhouse gases) are growing even faster than was predicted at the beginning of the 1990s. The various global environmental challenges we are facing are well documented and widely reported by the media. More and more people are expressing alarm and are agreeing that 'something should be done'.

As is often the case, however, what people espouse and what they actually do are frequently quite different (for a more comprehensive development of espoused and behaved values, see Argyris and Schön 1978). Widespread changes in consumption patterns and resource usage have not happened. In this chapter I argue that people have to become aware of and question widely shared collective thinking patterns, or mental models, before they can act in new ways.

1.2 Why attention to prevailing mental models is essential

Whatever outcomes we realise in describing and implementing sustainable practices, it is clear that the future quality of life will be dictated by human behaviour, which is driven by human thought. We have no choice about whether we will play a role in creating the future. Our only choice is whether to create the future consciously or unconsciously!

The relevance of generating awareness and choice about mental models in teaching sustainability can be summarised by the following three statements. The first is from Marilyn Ferguson:

If I continue to believe as I have always believed, I will continue to act as I have always acted. If I continue to act as I have always acted, I will continue to get what I have always gotten.1

This statement supports the notion that how we think strongly influences how we act, and our actions, in turn, influence the results we get. Trying to get different results (e.g. more sustainable management practices) while continuing to think in the 'same old ways' is not likely to lead to much change. Our mental models tend to be self-reinforcing and self-fulfilling.

The second statement is a paraphrase of an idea often expressed by Albert Einstein:

You cannot expect to be able to solve a complex problem using the same manner of thinking that created the problem.

Einstein's famous statement reminds us that if we do not adopt new mental models we will at best only be able to put short-term band aids on symptoms arising from unsustainable human activities.

Ferguson tells us that our thinking influences the results we get, and Einstein reminds us that a different consciousness will be needed, but the real challenge to teaching sustainability is represented by an observation from R.D. Laing, who suggested:

The range of what we think and do is limited by what we fail to notice. And because we fail to notice that we fail to notice, there is little we can do to change; until we notice how failing to notice shapes our thoughts and deeds

(Abrams and Zweig 1991: xix).

This third statement places the others within the reality that we are generally unaware of the mental models we use. So, an early priority in any sustainability education programme must be to raise awareness of the mental models being used and then to encourage responsible and conscious choice for adopting more appropriate mental models. If our attempts to teach sustainability in academic and corporate classrooms are to lead to significant action, we must help learners to understand and address their own default mental models and then show them how to diagnose and nurture versatility in the thinking of those they seek to influence.

A further implication for teaching sustainability is that the agent of change moving towards increased sustainability, whether she or he is an employee or a consultant, needs to be able to vary her or his mental models to exert successful influence. For example, if her or his opening message comes from mental models similar to those of the receiver, then less defensiveness is generated. Once discussion is under way, the agent of change can gradually shift her or his mental models and those of the person being influenced towards outlooks more appropriate to generating sustainable practices.

Mental models are with us from the very beginning. Owing to continual, normal repetitions and reinforcements, each of us gradually develops persistent ways of thinking that are assumed tacitly to be accurate reflections of reality and that operate, for the most part, unconsciously. Let us turn our attention now to some of the most prevailing collectively held mental models.

1.3 Prevailing mental models in North American organisations

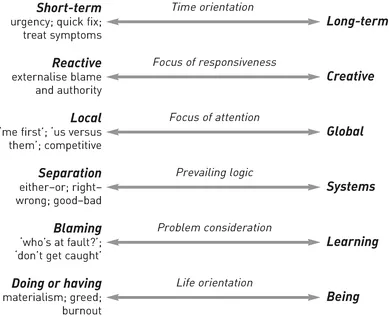

Over the past several years, I have regularly asked people in my graduate courses and in private corporate workshops to brainstorm about their experiences of the commonly held mental models in their organisations, asking them to use adjectives to describe the widespread norms and outlooks. After collecting dozens of these lists and thousands of descriptive adjectives and then sorting the items into themes, I have found that most of the items fall near the left extreme of the six dimensions portrayed in Figure 1.1. Please note, I do not think that these six dimensions provide a complete description of the consciousness needed for a truly sustainable future, but they certainly give us a running start.

Figure 1.1 Six key dimensions of a sustainable consciousness

Unanimously across every one of my classes and workshops, people have located the present default mental models in business at or near the left-hand side of these dimensions, with a rather narrow 'zone of comfort' around each. When asked what sort of scenario we will create in 20 years if these defaults continue unchanged, the responses are always gloomy—and decidedly unsustainable. When asked if these default mental models are driving the major ecological challenges and economic disparities that exist around the world, there is a unanimous 'Yes!' Although we already know what is needed, the autopilot nature of our prevailing default mental models is very persistent.

What would happen if we were able to shift the defaults significantly to the right, and generate wider 'zones of comfort'? Would we not be better able to create the kind of future we really want? For that matter, would we not also be able to bring our own lives into better balance today if we made these changes?

The challenge is that our mental models have a way of protecting themselves from change and usually operate like an autopilot. As far as we know, we are the only species on Earth that has the capacity to think about how we think. Most of the time, however, we do not engage this capacity. We reinforce our outlooks by repeating the same thoughts day after day. To take responsibility, we must move from autopilot to choice. In this respect, we have done a reasonably good job of preparing for the future technologically, but we have a long way to go psychologically and emotionally Box 1.2, at the end of this chapter, lists some of the success factors needed to bring about real change in deeply ingrained habit patterns such as mental models.

In the workplace, we often find that plans are created but not followed. We are constantly faced with examples of low integrity and questionable ethics in the arenas of business, finance, government and even childcare. When it comes to the environment, relatively few—although their numbers are growing—organisations voluntarily restrict themselves with regard to toxic emissions and solid waste disposal and, where regulations exist, minimum compliance—or finding loop-holes—unfortunately still prevails.

At the individual level, it seems too few people feel personally responsible for their lot in life. The act of taking personal responsibility for other than personal economic gain, although increasing, is still not widespread. Not enough of us recognise how small and endangered the Earth has become, and even fewer of us realise the many things we can do locally to address, even in a small way, some of the larger challenges.

Are people by nature self-destructive? Do people generally not care if they degrade the environment until vast tracts become uninhabitable? Are people unconcerned about the legacy they appear to be leaving for their grandchildren? Do people really think that their lifestyle habits will not have any consequences? Do wealthy Westerners really feel that it is appropriate for four billion fellow humans to live on less than US$2 per day? For most people, the answer is 'No!' to each of these questions, and yet the problems continue to grow.

I think the reason for this contradiction lies in our way of thinking. But mental models are not immutable. With conscious choice they can become more appropriately flexible. Versatility in consciousness is a key concept that needs to be introduced into the educational process at all levels if we are to address rising worldwide sustainability issues effectively. I believe that versatility in consciousness is essential for ongoing individual learning and that the only sustainable consciousness is a continual learning consciousness.

Any 'reprogramming' of the autopilot will require the same processes that established the present mental models in the first place—repetitions of messages and experiences. The reiterations of new ideas and intentions must be carried out consciously. Often, to get beyond the status quo maintenance efforts of the old autopilot it is necessary to create structures or mechanisms that require new repetitions be carried out.

It is easiest to change one default message at a time. Wholesale changes of one's consciousness, a complete personal transformation, is possible and sometimes happens, but step-by-step change is likely to be a lot easier for most people to assimilate.

1.4 Implementing the s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: Theory, critique and ideas

- Part 2: Learning from current practice

- Part 3: Tools, methods and approaches

- List of abbreviations

- Author biographies

- Index