![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

The industrialization and de-industrialization of agriculture

Farming: The practice of agriculture.

Agriculture: The science or art of cultivating the soil, harvesting crops, and raising livestock.

Polarization: A sharp division, as of a population or group, into opposing factions.

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, unabridged (Gove, 2002)

There are no gains without pains.

Benjamin Franklin, The Way to Wealth (1758)

Introduction

The growth of agriculture – in many ways, one of the greatest success stories in all of human history – has resulted in criticism, opposition, and increasing divisiveness in many issues in the food and agricultural sectors. Farming is not only the most important, but also the oldest continuously operating industry on Earth. For uncounted millennia, early homo sapiens depended on hunting and gathering for their food and for the materials needed for protection against adverse weather and other aspects of the environment. During this time, early peoples undoubtedly noticed the cycles of plant and animal growth and perhaps noted that, within limits, rearranging the growth characteristics of plants and animals could yield more uniform and more satisfying products. This was the beginning of agriculture. Little additional knowledge about those beginnings survives. Informed study suggests, however, that approximately 10,000 years ago – the exact year or era is not certain – humans began to exert some control over the production of their food and the manufacture of their clothing. Gaining this control, or even partial control, was not an easy task. It required knowledge of the plants and animals, their growing habits, the environment, and the means of preparing edible food and protective clothing from unprocessed plant and animal materials. Each step in the path from raw material to finished product may have taken years or even decades to perfect. These endeavors allowed important changes in human societies and behaviors. Relieved of the constant need to hunt and gather, and assured of at least a minimally adequate supply of food and clothing, humans could spend time in pursuits that made life fuller and helped expand their knowledge of the world.

It is not clear where farming began. Quite likely, the control of animals and crops began in several places at about the same time. Climate undoubtedly played a part, as did the traditions and superstitions of the people themselves. There may have been some random attempts at selective breeding of plants and animals, but most systematic progress in plant and animal development did not begin until agriculture embraced the methods of science during and after the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. From that time to the present, science, coupled with experience, imagination, and inventiveness, took over and generated a constant stream of changes that improved the ability of humans to produce food and fiber that was superior in production and superior in use. Producing food became more efficient, fiber became stronger and more durable, and animals converted fewer and fewer quantities of feedstuff’s into greater quantities of useful products: meat, eggs, milk, hides, and the like. After the beginning of scientific, or well-disciplined farming, populations of humans the world over began to enjoy a constant stream of progress and improvement in the world’s agricultural systems.

BOX 1.1: THE BEGINNING OF AGRICULTURE

Agriculture likely began about 10,000 years ago. Surely, before that time, some primitive farming activities were taking place in Africa, the Middle East, and in Asia. By that time, potato cultivation had begun in the South American Andes, and maize production stemming from its ancestor, teosinte, began soon after in mid-America. Even with these scattered hints regarding the development of agriculture, the major continuous development of human involvement with the production of food and fiber appears to have occurred in the Middle East’s Fertile Crescent. This crescent is a vast area that runs from the mouth of the Nile River to the eastern edge of the Mediterranean Sea then continues north and east before turning south to follow the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers to the Persian Gulf. In earlier centuries, the region had fertile soil and sufficient moisture to grow edible plants that eventually became cultivated crops.

The area was home to seven crops important to the development of early agriculture: emmer wheat, einkorn, barley, flax, chickpeas, peas, and lentils. Additionally, four important species of domesticated farm animals – cows, goats, sheep, and pigs – lived in or near the crescent. The area was highly productive and, although many crops grown there also grew in other places, the Fertile Crescent is the region in which agriculture, or farming, likely acquired a measure of discipline, and farmers began to flourish.

Global agriculture

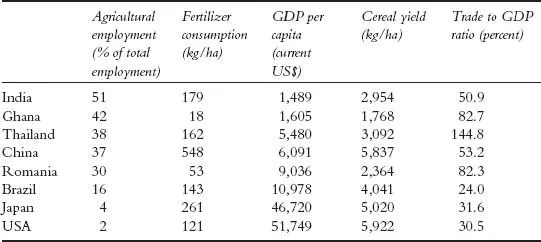

Agricultural growth and increased food production allowed early societies to expand their activities into nonfarm pursuits, leading to a decrease in agriculture’s share in the total economy. This trend continued, unabated, as economies grew and incomes rose. This universal trend is illustrated in Table 1.1, where the 2010 share of agricultural employment for eight diverse nations is shown, together with per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP, a measure of output per person), and cereal yield, a measure of agricultural productivity.

A clear and striking relationship is evident: wealthier nations have smaller agricultural labor forces relative to the rest of their economies. The transition from agricultural to nonfarm economies receives detailed treatment in Chapter 4. Table 1.1 also demonstrates that nations with higher levels of agricultural productivity (as measured by cereal yields) also have higher levels of output per capita. While the trend is strong and obvious, it is less clear whether agricultural productivity causes economic growth, or vice versa. Interestingly, economic growth requires the movement of workers out of agriculture: if every individual were a farmer, society would produce only food. As agricultural productivity increases, an economy becomes capable of producing consumer goods including houses, automobiles, more comfortable clothes, and a host of electronic devices that make living easier, more efficient, and more entertaining. The availability of these goods requires workers to migrate out of agriculture and into nonfarm pursuits.

The fundamental relationship between income growth and agricultural change is an underlying characteristic of many, if not most, of the polarizing issues in food and agriculture: progress and growth require change. The book’s primary thesis can be summarized as follows:

• Progress requires change.

• Change can be disruptive, difficult, and it produces winners and losers.

• Therefore, progress can be polarizing.

TABLE 1.1 Global agriculture summary statistics for eight representative nations, 2010

Sources: World Bank Data data.worldbank.org, 2014 (columns 1–4); World Trade Organization. Statistics Database, stat.wto.org, 2014 (column 5).

The remaining chapters of this book evaluate the causes, consequences, and possible solutions of polarized issues in food and agriculture. Progress in agricultural productivity is often a cause of polarization. Scientific discoveries and practical enhancements in agricultural production methods can be controversial. Some groups such as the Amish in the United States (US) do not use electricity or mechanical power, relying instead on horses to provide the power needed for agricultural fieldwork. There are numerous ways to produce food and fiber. Table 1.1 shows a great disparity in fertilizer use across the eight representative nations in 2010. Fertilizer and chemicals used to enhance food and fiber production have both benefits and costs: increased yields (benefits) can come at the expense of environmental quality (costs). Tradeoffs that occur with each production technique will have proponents, opponents, advocates, and detractors. This is true for countless agricultural techniques, whether they be pesticides sprayed on crops to eliminate weeds, insects, or fungi, growth hormones and antibiotics used in meat production, or genetic modification of crop seeds to capture productivity-enhancing attributes and traits. Advocacy for or against these techniques is often determined by self-interest, or the economic impact of the technique or method on an individual or group. The book highlights the economic motivation behind advocates and activists on both sides of each issue.

Some economic motivations are straightforward, such as the desire of many producers to adopt and use cost-saving or output-enhancing technologies such as Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), chemicals, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, or large-scale animal production facilities. In other situations, motivations are more complex. In interactions between affected parties, the actions of one group may affect the well-being of other groups. For example, if local food becomes popular, it could reduce the returns to conventional and organic food produced at some distance from consumers. Game theory, or the analysis of strategic interactions, is described in Chapter 10, and used to derive potential solutions to polarized issues.

International trade of agricultural products has become more important over the past several decades, as technological advances in transportation and communication have reduced the costs of moving food across national borders. The ratio of trade to a nation’s GDP indicates the importance of trade to a nation (Table 1.1). The share of trade is large for all of the eight selected nations, indicating the universal significance of trade. This theme is further investigated in Chapter 9. Disputes in agriculture have occurred since the advent of progress, because technological advance is the foundation of disruption and change.

Polarization and agriculture

The extent and diversity of early agriculture in human society caused the industry and its supporting industries to influence all except the most reclusive of the world’s residents. This interconnectedness brought with it typical human behaviors: it caused factions and animosities as well as alignments and realignments of trust and opinion relating to how farmers in all their diversity, and consumers in all of theirs, should react to each other. For example, should nations in Sub-Saharan Africa seek self-sufficiency in food by producing all of their caloric and nutrient needs, or would it be better for them to specialize in high-value exportable crops, and rely on less expensively produced food imports from other nations? Should European nations subsidize food production to become self-sufficient food exporters, or purchase food at lower cost from other nations?

How should ranchers who want to graze cattle on the vast acreages of the US Northern Plains react to farmers who want the same land divided into small “family” farms? How should bankers relate to farmers who have only a vague hope of being able to pay off the loans needed to purchase land? How should the US railroad magnates decide whether to lay rails through a northern pass (and instantly bring wealth to the towns along this route) or through a southern pass and thus condemn the northern towns to poverty or oblivion? Should farmers use agricultural chemicals to eliminate pests such as insects, crop diseases, and weeds? Should meat producers enhance productivity with growth hormones, antibiotics, growth promoters, and other pharmaceutical products? Should highly productive nations send their food surpluses to food-short nations, or will this result in dependencies and reduce incentives for domestic food production? Should farmers in the European Union (EU) adopt and grow genetically modified seeds to enhance food production, or avoid genetically engineered foods due to a host of uncertain and untested risks to the environment and long-term human health? The coming chapters discuss some of the complexities, and possible consequences of disputes and differences among farmers and between farmers and other groups. The narrative also describes some of the effects that these situations have had on farms, farm people, the broader industry, and food.

The Green Revolution, a term used to describe intensive research and development of food production during the 1940s to 1960s, provides an example of a major application of science to reducing human misery and hunger. It is also controversial because of a number of unintended consequences, highlighted below. Similarly, genetic modification of seeds used to produce food has provided what is perhaps the single most important contribution to increasing food production in the history of agriculture. Even so, many nations – rich and poor – ban genetically modified food because of the real or imagined risks that surround their use.

Neither agriculture nor economics has a word that suitably describes the problems engendered by the disputes and “uncomfortable situations” that develop when people interested in the same (or similar) goals choose to take incompatible paths toward reaching them. For that reason, the discussions here borrow from contemporary sociologists and political scientists who use the word “polarization” to describe the division of opinion. Two examples help convey this use of the word. Both examples have intelligent, reasonable, and caring individuals on each side of the issue.

Example 1: polarization in the beef industry

In the early years of the twenty-first century, nutritionists and other research scientists reported that eating beef could be harmful to human health. At approximately the same time, groups in many parts of the world questioned beef production because of the environmental damage done by beef animals trampling native pastures as well as discharging large volumes of intestinal gas and other body wastes that eventually contributed to global warming and other environmental problems. During the same time, animal rights advocates opposed the use of confined feeding facilities as an inhumane way to fatten beef animals. As if this were not enough, groups worrying about the adequacy of the world’s food supply made strong arguments that beef animals are inefficient producers of calories – the same resources used to support the animals could produce significantly more calories (and other nutrients) if used to produce food grains, fruits, and vegetables – especially beans, peas, lentils, and other legumes.

Beef producers, processors, and beef industry organizations felt obligated to respond. These groups mounted their own research efforts and used print, radio, and electronic media to assure the beef-eating public that beef is nutritious and has a worthwhile place in human diets. Such strong disagreements between nutritionists, food producers, processors, and consumers are increasingly public and increasingly acrimonious. The arguments and the positions taken by the participants in these disputes have polarized conversations across the entire industry. These contrasting views require large amounts of societal resources from both sides of the issue; resources that could be used to produce goods and services.

The conflicts and confusion apparent in the above paragraphs go well beyond beef to include a more general category of meat or animal-based food supplies.1 The existence of the conflicts begs a serious question: How did things get the way they are? One response says simply that food production (and consumption) has always brought contention, jealousy, envy, and enmity among those who are involved in the processes. Answering this question in a reasoned and complete way requires scrutiny of perhaps 10,000 years of human history – the time during which homo sapiens emerged from their millennia of hunting and gathering, domesticated plants and animals, and learned to exert some control over the production of foods and fibers (Mazoyer and Roudart, 2006).

It has not always been this way. A commonly held, nostalgic, and romantic view has the yeoman farmer “doing God’s work” earning a livelihood by tilling the land and caring for the animals. Similarly, the idea of a family farm carries a strong emotional impact even today, when a small percentage of the population in high-income nations lives and works on farms (Table 1.1). The one feature of agriculture that has remained constant is continuous change: enormous productivity growth and changes in the production, processing, and consumption of food.

Example 2: the Green Revolution in India

Since the 1960s and 1970s, the “Green Revolution” has referred to the development and adoption of high-yielding seed varieties in agricultural nations. After World War II, international agricultural research centers were founded and funded primarily through private American institutions, including the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. The Green Revolution enhanced agricultural productivity enormously in many Asian and Latin American nations, but less so in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Green Revolution allowed India, food-short for decades, to become self-sufficient in food grains: wheat and rice. After ...