![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Situating smart cities

Andrew Karvonen, Federico Cugurullo and Federico Caprotti

Introduction

The era of the smart city has arrived. Only a decade ago, the promise of improving and optimising urban services through the application of information and communication technologies (ICT) was largely a techno-utopian fantasy. Today, smart urbanisation is part and parcel of thousands of urban projects around the world. Canonical examples of smart cities such as Songdo, Masdar City, PlanIT and Rio de Janeiro (Halpern et al. 2013, Carvalho 2015, Cugurullo 2016, Luque-Ayala and Marvin 2016, Pinna et al. 2017, Wu et al. 2018, Datta forthcoming) have given way to ‘the actually existing smart city’ (Shelton et al. 2015) where ICT is rapidly being woven into new and existing urban policies, agendas, narratives and aspirations. March and Ribera-Fumaz (2016: 816) note that ‘every city wants to be a Smart City nowadays’. And, more importantly, a plethora of cities are gradually turning the rhetoric into reality: they are becoming smart cities.

This collection responds to recent appeals for empirical and comparative accounts of contemporary smart cities (Kitchin 2015, Shelton et al. 2015, Wiig and Wyly 2016). While the smart city is being realised in tangible and ordinary locales, there is scant evidence and critical reflection on how this is taking place. From an empirical perspective, this is understandable as the smart city is difficult to pin down and assess when compared with the more tangible elements of contemporary cities such as skyscrapers, reinforced concrete and sewer networks. The sensors and datahubs of smart urbanisation are largely invisible and tend to lurk in the background. However, they have fundamental implications for how cities will operate and how they will be experienced by residents in the future. Thus, there is a need to get inside smart cities to reveal the influence of digitalisation on broader urban dynamics.

The contributions in this volume provide real-world evidence on how the notion of smart urbanism is rapidly being interpreted and applied in 23 cities across the globe. Drawing upon theories from urban geography and planning, innovation studies, science and technology studies and related disciplines, the contributors reveal how the digitalisation agenda is being situated in particular political, social and material contexts. The chapters span the Global North and Global South; involve projects and initiatives with both high and low profiles; describe combinations of mundane and cutting-edge technologies; and reveal how consortia of local and non-local actors from the public, private and third sectors (as well as urban residents) are grappling with the rapidly emerging smart city in its various forms.

The empirical findings reflect the diversity of contemporary applications of smart urbanisation, shifting the focus of smart city scholarship from its technological promise to its real-world application. It is important to stress that innovation is not only technological. Instead, it involves a series of changes that are economic, sociocultural, architectural, ecological and political. These different forms of innovation collectively feed into the larger dynamics of urban planning, development and operation (McFarlane and Söderström 2017, Cugurullo 2018). Moreover, these innovation processes are recursive: smart changes cities and cities change smart through iterative processes of situating, embedding and learning (Carvalho 2015, Kong and Woods 2018).

In the following sections, we briefly summarise the rapid evolution in smart urbanisation from aspiration to application. We then summarise the contributions in this volume, using a thematic framework to characterise the situating of smart as processes of grounding and contextualising, integrating and aligning, contradicting and challenging, and experiencing and encountering. As a whole, the chapters illustrate how urban innovation is being negotiated and interpreted in a wide range of contexts, while also raising more fundamental questions about the rapidly evolving relationship between society and ICT. As such, this is a fundamentally socio-technical perspective on contemporary cities that explores both the positive and negative implications of smart urbanisation. The findings are relevant to academics, policymakers, practitioners and other urban stakeholders who are grappling with the present and future implications of smart cities.

Smart cities: from aspiration to application

Smart urbanisation is an increasingly common way for cities to innovate in the twenty-first century. Smart technologies are frequently promoted as universal, rational and apolitical solutions to address the myriad problems of contemporary cities (Shelton et al. 2015). Proponents suggest that ICT can simultaneously address issues of resource efficiency, surveillance and security, citizenship and participation, evidence-based policy making, behavioural change and social cohesion, and more. For example, a recurring mantra of smart cities’ advocates is that integrated ICT deployment is the key to realising the knowledge economies of the twenty-first century (Martin et al. 2018). However, beyond these vague ideas about innovation and collective urban services, there is little agreement on a single definition of smart cities, because of the numerous ways that it is being interpreted and applied. Various authors have characterised the notion of smart cities as ‘ambiguous’ (Vanolo 2014: 883), ‘elusive’ (Carvalho 2015: 45), ‘chaotic’ (Glasmeier and Christopherson 2015: 5) and ‘unstable’ (McFarlane and Söderström 2017: 315).

Haarstad (2016) contends that the smart city label is an empty signifier (similar to sustainability), and suggests that the definition is much less important than what smart cities achieve in practice. When considering what smart cities actually ‘do’ rather than how they are defined and promoted, it is clear that there is common drive to rationalise cities to make them more efficient, resulting in significant long-term cost savings. As Goodspeed notes, ‘The city is a system to be optimised or run efficiently’ (2015: 83, emphasis in original). The modern notion of rationalising the city through cutting-edge technologies and effective governance has been around for centuries (Graham and Marvin 2001). Ubiquitous infrastructure networks, comprehensive urban planning and municipal governance, capitalist expansion plans and sustainable urban development agendas have all promised to tame the unruly city. Today’s smart city advocates proclaim that ICT will finally integrate the various functions of cities into manageable and coherent wholes (Allwinkle and Cruickshank 2011, Luque-Ayala and Marvin 2015). This suggests that smart is much more than an opportunity for technology developers to position cities as primary marketplaces for their products. Instead, smart is being promoted as the fundamental ethos to manage and govern cities of the future.

For many urban stakeholders, the promise of rationalising cities and optimising collective services through innovation is an alluring proposition. Today, one-third of UK cities with populations over 100,000 have smart city ambitions (Caprotti et al. 2016) while two-thirds of US cities are investing in some form of smart technology (NLC 2017). The national governments of India, China and Singapore are promoting smart cities through competitions, funding programmes, policy agendas and pilot projects with support from transnational organisations (e.g., Joint Programming Initiative Urban Europe, Bloomberg Philanthropies) and technology providers (IBM, Cisco, Google). The European Union (EU) has been a particularly strong proponent of smart cities through the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme on Smart Cities and Communities, and has funded a network of over 50 ‘Lighthouse’ and ‘Follower’ cities since 2014 (Vanolo 2014, 2016, Haarstad 2016).

Municipalities are keen to use the enthusiasm for smart cities to reinforce and extend their existing development ambitions while enhancing their global rankings (Vanolo 2014). Innovation districts, urban laboratories, platforms and specialised districts serve as publicly visible showcases to provide tangible evidence that local authorities are forward-thinking and proactive urban actors (Karvonen and van Heur 2014, Goodspeed 2015, Evans et al. 2016). As Glasmeier and Christopherson (2015: 4) note, ‘The race to get on the bandwagon and become a smart city has encouraged city policymakers to endogenise the process of technology-led growth, directing municipal budgets toward investments that bestow smart city status.’ It is through smart urbanisation that cities can develop their global reputations as progressive (at least in techno-economic terms) and liveable places where companies and residents can thrive. In this way, ‘smart urbanism has become a normative aspiration for the urban future’ (Kong and Woods 2018: 681).

Of course, the ‘smartification’ of cities has also attracted significant criticism, largely from academics in the social sciences (e.g., Hollands 2008, 2015, Sennett 2012, Greenfield 2013, Söderström et al. 2014, Vanolo 2014, 2016, Viitanen and Kingston 2014, Kitchin 2015, Luque-Ayala and Marvin 2015, McFarlane and Söderström 2017). These authors argue that smart city visions and practices amplify and extend the contemporary neoliberal economic agendas of cities. They critique smart cities for their singular focus on efficiency and economic development through technological innovation. While the focus on problem solving and solutionism has obvious economic benefits to technology providers and urban authorities, it often fails to address the issues that are central to everyday life (Glasmeier and Nebiolo 2016, Saiu 2017, Cardullo and Kitchin 2018).

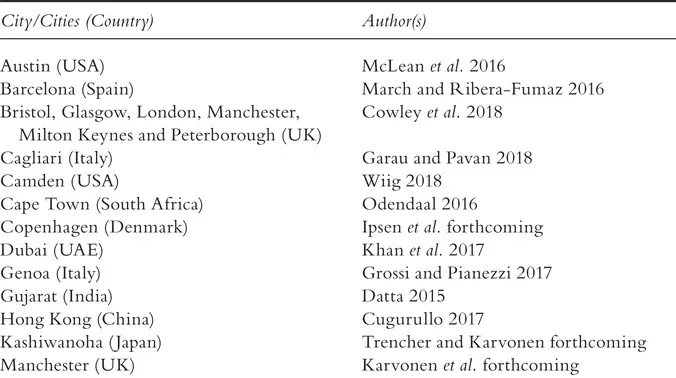

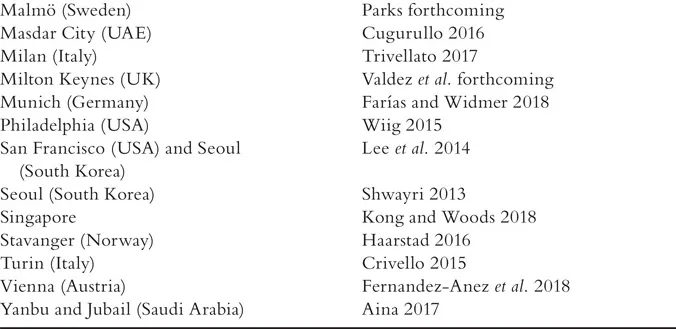

More recent scholarship on smart cities has moved beyond critique to observe and assess the processes and outcomes of those activities that are currently unfolding on the ground (Table 1.1). This shifts the smart city research agenda to focus on the situated characteristics of smart cities, bringing the urban qualities of the smart city into sharp focus (Wiig and Wyly 2016, McFarlane and Söderström 2017). Smart urbanisation becomes one of many influential drivers of urban development as it becomes embroiled in debates about politics, culture and society in ‘ordinary’ cities (Amin and Graham 1997, Robinson 2006). Corporations continue to play a significant role in the roll-out of smart city functions; but they have been joined by other stakeholders, including local governments, utility providers, small and medium enterprises, and civil society organisations. In this way, smart loses some of its novel and utopian character while becoming more relevant and applicable to the existing dynamics of urban development.

Situating smart cities

The contributions in this volume provide empirical evidence on how smart is being interpreted and embedded in particular material and social contexts. These are not comprehensive accounts, but instead serve as snapshots to illustrate the various activities that constitute contemporary smart urbanisation. They reflect a wide diversity of technologies and actors, and demonstrate how broader processes of urban development are being conceptualised, funded, designed and realised under the banner of ‘smart’. In other words, the contributors show how ‘smart’ is doing different work in different places (McFarlane and Söderström 2017).

TABLE 1.1 Examples of empirical studies of smart cities

The challenge with empirical accounts of actually existing smart cities (and cities more generally) is that they are unavoidably complex and multifaceted. We have tentatively divided this volume into four thematic sections to highlight the prominent urban dynamics being addressed in each chapter: 1) grounding and contextualising; 2) integrating and aligning; 3) contradicting and challenging; and 4) experiencing and encountering. We characterise these categories as ‘tentative’ rather than definitive or absolute because the findings in each city resist discrete categorisation and address all of these themes to some extent. Thus, the themes serve as a heuristic tool to organise the contributions, while readers will undoubtedly identify other crosscutting themes of smart urbanisation.

Grounding and contextualising

Smart urbanisation does not occur in a vacuum. Cities are messy, diverse and heterogeneous. Therefore, smart technologies cannot be implemented and applied universally to the urban landscape. Instead, they need to be translated and configured to fit within their specific contextual conditions. Shelton and colleagues (2015: 14) note that ‘smart city interventions are always the outcomes of, and awkwardly integrated into, existing social and spatial constellations of urban governance and the built environment’. This requires a move away from a one-size-fits-all approach and towards piecemeal retrofitting through activities of tailoring and customising (Carvalho 2015, Glasmeier and Christopherson 2015, Kitchin 2015, Eames et al. 2018). Here, the smart technologies are less important than how they are applied in particular places. This also suggests that smart urbanisation is producing highly variegated urban landscapes with different levels of and approaches to service provision (Graham and Marvin 2001, Kong and Woods 2018).

The chapters in the first section of the book are organised under the theme of grounding and contextualis...