![]()

1 Istanbul

Nighttime Illumination in Istanbul

İpek Türeli

In his 1839 account of Constantinople, English architect Thomas Allom (1804–1872) observed that there were

no lamps to illuminate the city by night; no shops blazing with the glare of gas; no companies flocking to or from balls; or parties or public assemblies, of any kind, thronging the streets after night fall, and making them as popular as at noon-day … At sunset all the shops are shut up, and their owners hurry to their respective residences; and when the evening closes in, the streets are as dark and as silent as the grave.

(Allom, 2006, p. 116)

Italian novelist Edmondo de Amicis (1846–1908) echoes Allom in his 1871 travelogue: “Constantinople is by day the most splendid and by night the darkest city in Europe” (de Amicis, 1888, p. 130). Nighttime Constantinople is typically portrayed by European travelers as a dark city where most of the city’s inhabitants went to bed after the evening call to prayer, with exceptions that included the nights of the holy month of Ramadan, religious festivals, holy days, and other special occasions.1

During the month of Ramadan, practicing Muslims adhered in their daily habits to a different schedule from in the rest of the year. They abstained from food and drink from dawn to sunset each day. After the first meal of the night, the fast-breaking dinner, both men and women socialized. Religious shrine and mosque visits for prayer or sightseeing were coupled with nighttime feasts, house visits, promenades, street entertainment that could continue until the pre-dawn supper, sahur, only after which the city would sleep (Göktas, 1993–1995; Kadioglu, 1993–1995). Even government offices observed this schedule (Beydilli, 1988, p. 517). Religious observance was communal, social, and entertaining.

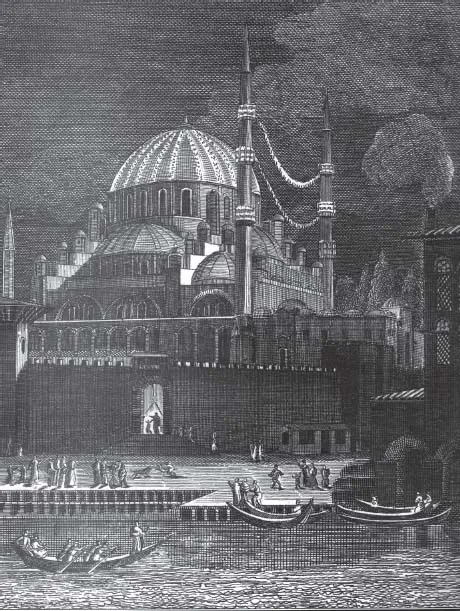

Of the two religious festivals, the Ramadan (Eid al-Fitr) takes place over several days to celebrate the end of the holy month. And roughly two months and ten days later, on the tenth day of the twelfth and final month in the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the Kurban (sacrifice, Eid al-Adha) festival takes place in memory of the ram sacrificed by Abraham in place of his son. Religious nights—Mevlid, Ragaip, Mirac, Berat, and Kadir—are also celebrated by Muslims around the world.2 On these nights, mosques and important shrines are open to the public, sometimes with special programs. The names of these holy nights (except Kadir Night) have been supplanted in Ottoman-Turkish with kandil (e.g., Berat Kandili), after the Ottomans adopted, in the latter part of the sixteenth century, the tradition of using kandil—an illumination device with oil and wick; which probably derives from Latin, “candle”—to light up the minarets of mosques. In the early seventeenth century, this practice was expanded from holy days to Ramadan nights, and a new practice of hanging illuminations between minarets of sultan mosques was developed. These hanging illuminations, which featured religious words and phrases, were called mahya. During Ramadan and other holy nights, streets would be informally lit with lanterns hung by shops and coffee houses some of which would be open until dawn. With individuals carrying their own lights on their way to sultan mosques and shrines, or simply promenading, the crowd on the streets would resemble a convoy of “fireflies” (Adivar, 2009, p. 57).

Figure 1.1 “A mosque” by S. N. Glinka, 1996, Gravürlerle Türkiye, Türkiye in Gravures, V1, Ankara: T.C. Kültür Bakanlği, Yayimlar Dairesi Başkanliği. p. 30; reproduced from Obozrenie vnutrennosto Turtsii Evropeyskoy, pocerpnutoe iz’ drevih’I novih… by S. N. Glinka, 1829, pp. 4–5

The association of artificial light with religion is a shared theme in the region. Byzantines lit wax candles in churches and cemeteries. After the Ottoman takeover of the city (1453), Muslims adopted some of the local traditions such as lighting candles in shrines with tombs (Kuban, 1993–1995). Candles continued to be the main method of nighttime illumination. Beeswax, animal fat and, later in the nineteenth century, imported whale fat were favored materials. In residential buildings, they were used in candleholders, made of materials such as wood, metal, ceramic, and glass. Gas lamps were adopted in wealthier households in the nineteenth century because they provided a brighter, stronger light. In mosques, which were not only religious but also public spaces, two kinds of light sources were used: large candleholders to the sides of the mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) and large chandeliers hung from the ceiling to illuminate the central space of the mosque. Finally, outside, on the streets, torches or lanterns were carried by night watchmen and ordinary citizens.

Beyond these exceptions, nighttime was heavily monitored. Occasionally sultans imposed curfews; it was forbidden to be outside without a lantern after the evening prayer during the reign of Murad IV (1623–1640) (Toprak, 1993–1995, p. 476). The regulation of nighttime was intimately connected to the regulation of public space and the dominant model of sovereignty.

After the takeover of Constantinople by Sultan Mehmed II, Ottoman sultans adopted a protocol of seclusion. Everyday life was controlled in each autonomous administrative unit (Işın, 2001). Unlike Orientalist depictions, women were not constrained to the harem or interiors, they could be seen out and about. However, the use of public spaces was highly gendered. Coffee houses and courtyards of mosques were the domain of men; women could access bazaars, market places, religious shrines, and fountains. Picnic grounds outside the city proper provided opportunities for collective recreation.

Starting in the early eighteenth century, Ottoman rule forged a new image for itself, based on visibility. The royal family returned to Constantinople after a forty-year absence, spent in Edirne, started restoring old palaces and their gardens, and commissioned new ones (Hamadeh, 2008). Ahmed III who ascended the throne in 1703 was interested in kiosks and summer palaces outside the confines of the older and architecturally sterner Topkapi Palace. His and his retinue’s promenades were sightseeing opportunities for the general public. Frequent entertainments, including nighttime ones, were held in the new locations.

The nighttime festivities held in the gardens typically decorated by tulip beds featured burning lights under every tulip; and tortoises were seen meandering with candles on their shells—referred to by Osman Hamdi in his famous painting, “The Turtle Trainer” (1906) (Mélikoff, 2011). Barges carried the general public near these palaces, the gardens of which were visible and audible but not physically accessible. Complementing exclusive palace gardens, the sultan, members of his extended household and high-ranking officers sponsored new fountains and gardens for the public (2008). Pleasure gardens of Ahmed III would incite violent opposition and the famed Sadabad Palace and gardens (in today’s Kagithane) were burned down after his deposition in 1730. This period, dubbed the “Tulip Period,” after the tulip obsession among Ottoman court society, is seen in conservative histories of the Ottoman Empire as the beginning of the “Stagnation Period,” or invariably as the beginning of “Westernization.”

Nighttime Illumination as Municipal Service

In 1855, a municipality was established in Constantinople to centrally provide modern urban amenities (Arnaud, 2008, pp. 953–976, 1399–1408). The first contract of 1864 dealt with the installation of street lighting that used petroleum imported from the United States, where large quantities of the material were discovered and put to use as a popular fuel (Toprak, 1993–1995, p. 476). Petroleum storages in Constantinople were kept outside the city, in depots, for fear of conflagration. Coal-gas was introduced in the Dolmabahçe Palace, during the reign of Sultan Abdülaziz (1839–1861). A gazhane, gas production plant, was constructed to provide the new palace—the excess from this facility then supplied Istiklal Avenue (Rue de Pera) and Galip Dede Street in today’s Beyoglu neighborhood (Akbulut & Sorguc, 1993–1995, pp. 377–378). The historic peninsula was illuminated with street lighting later with the establishment of the Yedikule plant in the 1880s.

The regularization of the urban fabric and the accompanying institutionalization of street lighting in Constantinople were considerably late compared to other European capitals. London begun using coal-gas for street lighting in 1810, and Paris adapted coal-gas in 1820 and electricity in 1878 (Toprak, 1993–1995).3 For fear of earthquakes, the Ottoman state had encouraged wooden construction in the historic peninsula, but the prominence of that material made the city particularly susceptible to large fires (Zwierlein, 2012). As far as the Ottoman Empire is concerned, the adoption of electricity in the capital city arrived later than in its provincial Arab capitals. It was during the Second Constitutional Era (1908–1918), when the Young Turks seized power from the sultan and restored constitutional monarchy, that the city’s first coal-powered electricity production plant, Silahtaraga, was commissioned to a Budapest-based company.4 Silahtaraga remained the sole provider of the city until 1952 when it was connected to the newly established national grid. It was decommissioned in 1983 and has been converted to the privately-owned Bilgi University in the past decade as part of a culture-led revitalization effort around the Golden Horn, the city’s former industrial zone (Türeli, 2010). Although Silahtaraga was operational by 1914, it provided mainly the tramlines, and a limited network of street lights with power. By the 1920s, only primary and some secondary streets were lit with electricity. The Republican years (1923–1950) focused on industrialization; electricity production and access were prioritized. But it was not until the 1980s when city authorities decided to de-industrialize the central city to make space for cultural tourism that they began thinking about how the city was lit or what kind of image it projected. Creative architectural and city lighting schemes are highly sought after by the city administration.

The Ottoman Art of Urban Lighting: Mahya

Mahya is a specifically Ottoman tradition and originated in the city. It is viewed as a traditional art, “gradually flickering” (Zaman, 2007). Eccentric collector-writer, artist, and medical doctor, professor Süheyl Ünver (1898–1986) wrote, in 1932, an authoritative article on mahya (Ünver, 1932, 1996).5 He reports mahya began to be used in all sultan mosques only in the Tulip Period (Quartet, 2005, p. 167). Many of the secondary sources cite German traveler Salomon Schweigger’s account and illustration of mahya in Constantinople in 1578 (Schweigger, 1619, p. 193).6 The illustration is of utmost importance but it may be partially fictive. First, a mahya cord is strung between the minarets of two different mosques, which is unrealistic (Kara, 2013, p. 22). Second, there is no religious inscription; the drawn kandils seem to make up geometric figures. Ahmed Rasim’s account is used to date the invention of mahya to Hafiz Kefevi, the kandilci of Fatih Mosque, who, according to the much repeated story, presented to the sultan a version, and the sultan agreed to him setting up a mahya featuring a calligraphic inscription from the holy book, between the minarets of Sultan Ahmed (Blue) Mosque as part of the inauguration festivities of that mosque in 1616 (2013).

The word mahya derives from mah (moon) in Persian; with the Arabic suffix of “iyye,” to mean “specific to the month” (of Ramadan)—since Muslims used the lunar calendar, moon means month in Turkish (Bozkurt, 1988, pp. 396–398).7 Another Arabic word transliterated similarly is mahyâ. The two have different meanings but are nevertheless connected. Mahyâ shares the same root with “life” (hayat), and was used to refer to the zikr (chanting of the greatness of Allah) assemblies (1988). The Ottomans’ innovation in the development of mahy...