![]()

1 Topographic surface

In this chapter we explore the potential of digital technologies for designing topography. We begin with a discussion of design explorations and theoretical writing emerging in architecture during the late twentieth century. At first glance, this might seem odd for a chapter focusing on topography. However, as will soon become apparent, the transformative moments in architecture in the 1990s, form an important foundation for understanding concepts and techniques now being adopted in landscape architecture. Throughout this chapter these new cross-disciplinary concepts will be explained and contextualised within landscape architecture. This discussion should also be considered in conjunction with the time line of ideas and technological developments featured in the Introduction.

The work of Ivan Sutherland was a major catalyst for what has become known as computer aided design (CAD). In 1963, Sutherland developed the Sketchpad computer program (also described as Robot Draftsmen) as part of his Ph.D. studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). His work highlighted the potential of computer graphics to be used for both technical and design purposes, while also proposing a unique method of human–computer interaction. Importantly, Sutherland’s work can be considered the first example of parametric software, a concept which will be introduced in more detail further in this chapter.1

Following Sutherland’s influential lead, developments in CAD evolved in two key directions; first, in the ambition to develop a computer graphics system for interactive drawing, and, second, in the exploration of the computer’s potential to inform methods of design more directly. In the first case, computer graphic systems were sufficiently developed to be released into industry by the early 1980s – ArchiCAD became available in 1982 (considered the first CAD product for use on a personal computer, the Apple Macintosh), followed by AutoCAD in the same year. These two systems were adopted as industry standards for 2D and 3D drafting and technical drawings across architecture, engineering and landscape architecture throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. However the application of computer graphic systems by most designers remained limited to the translation of established representational conventions such as plans, sections and elevations into digital files; essentially drawing through a digital means.

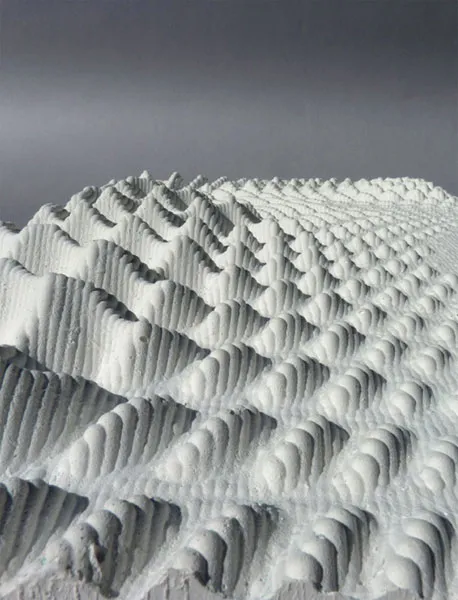

1.1

Knob land form, Fall Foundational Studio 2013, University of Virginia.

In contrast to simply replicating the pen with the mouse, the second approach sought to explore the computer’s ability to influence design generation. This work focused initially on the concept of object-based architectural grammars and spatial allocation techniques for rationalising approaches to design, popular during the 1970s and 1980s. This emphasis on the ‘computability of design’ in many ways mirrored the rationale approaches proposed by GIS which was unfolding in the same period. The work of Architecture Machine Group established in 1968 at MIT, which evolved into the Media Laboratory, was significant. Director William J. Mitchell produced two seminal texts Computer-Aided Architectural Design in 1977 and The Logic of Architecture: Design, Computation and Cognition in 1990. Building on the influence of geometry in determining architectural form, Mitchell conceived of architecture as a series of formal grammars that could be modified through the application of grammatical rules.

While these early object-driven design explorations had limited application to landscape architecture, this was to alter in the 1990s when architects became interested in the potential of non-Euclidean geometries, which had first emerged in mathematics during the early nineteenth century. During this period, mathematicians developed geometric alternatives to Greek mathematician Euclid’s planar and solid geometries described in his treatise Elements. Euclid’s fifth postulate proposed ‘that for any given infinite line and point off that line, there is one and only one line through that point that is parallel’.2 The publication of elliptical (or Riemannian) geometry and hyperbolic geometry challenged this postulate, and it was the possibilities of these new geometries as 3D surfaces that captivated the imagination of architects towards the end of the twentieth century.

This interest in the new potential of continuous surface combined with the emergence of a theoretical terrain aimed at addressing the tensions inherent between the two competing ideologies of Postmodernism; that of Contextualism and Deconstructivism, inspired a transformative move towards what could be considered an architectural ‘digital design practice’. The writing of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze was particularly influential. His essay ‘The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque’, which was translated into English for the first time in 1992, provoked spatial possibilities for envisaging concepts of complexity and contradiction, both pivotal Postmodern framings featured prominently in the work of the Deconstructionist-inspired architects.

Peter Eisenman was one of the first to explore Deleuze’s essay ‘The Fold’ in relationship to architecture. He was pivotal in articulating ‘a new category of objects defined not by what they are, but by the way they change and by the laws that describe their continuous variation’.3 For Eisenman, the notion of the fold offered an exciting alternative to gridded space of the Cartesian order, challenging the binary distinctions of the interior–exterior and the figure–ground. The exploration of these ideas was continued by Greg Lynn who, informed by Deleuze’s definition of smoothness ‘as continuous variation’, proposed new ways for conceptualising spatial complexities. His essay ‘Folding Architecture’, published as the keynote essay of a special themed issue of Architectural Design (AD) in 1993 is considered a turning point in the history of Deconstructivism in relationship to design. Lynn defined ‘smooth transformation’ as ‘the intensive integration of differences within a continuous yet heterogeneous system’ and identified the concept’s value in resolving the tensions inherent between the pursuit of Contextualism, order and composition versus Deconstructivism’s alternative focus on opposition, fragmentation and disjunction.4 Significantly, smoothness could be understood as a ‘mathematical function derived from standard differential of calculus’.5

Technological developments in hardware and software emerging in parallel provided the opportunity for architects to explore these theoretical ideas through space and form. The application of spline (understood most simply as a line that describes a curve) modellers in architecture sourced from the aviation and automobile industry was one of the most influential advancements, offering designers faster and more intuitive means for exploring calculus-based forms. These technological advancements fundamentally altered the designer’s relationship to the design process, blurring the boundary between software design and the designer through a series of new generational techniques such as parametric modelling, simulating and scripting.6

This moment of late twentieth-century architectural design history exemplifies the intrinsic relationship between technological opportunity and theoretical ambition, with both necessary for innovative outcome. The writings of Eisenman, Lynn, Stan Allen and Bernard Cache, together with design explorations by firms such as Foreign Office Architects and Frank Gehry offered compelling demonstrations of the potential of this theoretical terrain to inspire novel architectural form. This capacity was made possible through the innovative software and hardware developments, emerging from outside the architecture professions. Mario Carpo explains further:

So we see how an original quest for formal continuity in architecture, born in part as a reaction against the deconstructivist cult of the fracture, ran into the computer revolution of the mid-nineties and turned into a theory of mathematical continuity … Without this preexisting pursuit of continuity in architectural forms and processes, of which the causes must be found in cultural and societal desires, computers in the nineties would most likely not have inspired any new geometry of form.7

Throughout the 1990s the British journal AD formed a critical avenue for disseminating these design approaches and ideas (and continues to be a leading avenue for advancing a digital design practice). This period can best be summarised as a move from ‘the representational as the dominant logical and operative mode of formal generation’ to a focus on performative and material investigations of topological geometries.8 Accordingly, core design concepts such as ‘representation, precedent-based design and typologies’ are replaced by a new interest in ‘generation, animation, performance-based design and materialization’.9

Defining theoretical concepts

By the beginning of the new millennium, theories of architectural digital design practice were becoming more articulated, distilling into defined theoretical concepts. Frédéric Migayrou’s symposium Non-Standard Architecture held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2003 is recognised as a defining moment, along with the influence of discourse emerging from the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2000 and 2004.10 The three concepts of topology, parametric design and performance emerge, and are commonly acknowledged as foundational to a digital design practice. These concepts are introduced in the following section, and will be revisited in more detail in following chapters.

Topology

The concept of topology has its origins in mathematics and is understood as the study of geometrical properties and spatial relations which remain unaffected by changes in size and shape. For example a topological map (as distinct from a topographic map) is a simplified diagram that may be developed without scale, but still maintains the relationship to points. The London Underground map is an example where the map remains useful despite the fact that its representation shares little resemblance to a scaled plan of the Underground.11

Topology therefore offers a non-geometric manner in which to conceive space premised on the geometry of position.12 Topology departs from an understanding of space as Cartesian (where each point is identifiable by fixed coordinates) to instead embrace topological properties of space that encompass surfaces and volumes. A topological approach, often described as ‘rubber sheet’ geometry, evolves from the application of pressure on the outside of surfaces through modifying algorithms. The resultant surface-driven architectural forms became known as BLOB or Binary Large Objects Shapes, defined as the development of a mass without form or consistency. Within this framing ‘formation precedes form’ with design generation emerging through the logic of the algorithm, ‘independent from formal and linguistic models of form generation’.13 This shifts design thinking from a visual or compositional judgement to a focus on relational structures represented within codes, algorithms and scripts.

Parametric modelling

The adoption of algorithms in form making introduces a parametric approach to design, which is considered the dominant mode of digital design today. Algorithms define a specific process which offers sufficient detail for the instructions to be followed. They are also known as script, code, procedure or program, terms which are often used interchangeably. Similarly, parametric modelling can also be referred to as associative geometry, procedural design, flexible modelling or algorithmic design. In this book we adopt the term parametric modelling. So how is parametric modelling applied in the design of the built environment?

Traditionally, design emerges through the making and erasure of marks, which are linked together by conventions. But within parametric modelling the marks of design ‘relate and change together in a coordinated way’.14 Rob Woodbury notes that:

No longer must designers simply add and erase. T...