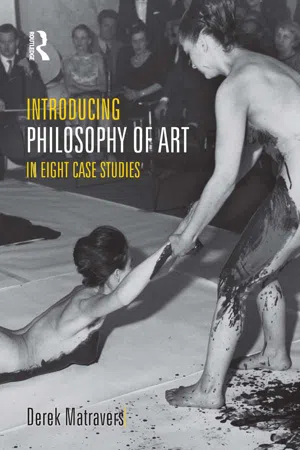

On a clear night in March [1960] at ten pm sharp a crowd of one hundred people, all dressed in black tie attire, came to the Galerie International d’Art Contemporain in Paris. The event was the first conceptual piece to be shown at this gallery by their new artist Mr. Yves Klein. The gallery was one of the finest in Paris.

Mr. Klein in a black dinner jacket proceeded to conduct a ten piece orchestra in his personal composition of The Monotone Symphony, which he had written in 1949. This symphony consisted of one note.

Three models appeared, all with very beautiful naked bodies. They were then conducted as was the full orchestra by Mr. Klein. The music began. The models then rolled themselves in the blue paint that had been placed on giant pieces of artist paper – the paper had been carefully placed on one side of the gallery’s wall and floor area – opposite the full orchestra. Everything was composed so breathtakingly beautifully. The spectacle was surely a metaphysical and spiritual event for all. This went on for twenty minutes. When the symphony stopped it was followed by a strict twenty minutes of silence, in which everyone in the room willingly froze themselves in their own private meditation space.

At the end of Yves’ piece everyone in the audience was fully aware they had been in the presence of a genius at work, the piece was a huge success! Mr. Klein triumphed. It would be his greatest moment in art history, a total success.

(Lewis 1960)

Above is a contemporary description of an event organized by the French artist Yves Klein (1928–62). After rolling around in the paint, the models pressed themselves against the paper, forming an impression of their bodies. Klein dubbed such works Anthropometries (“Anthropometry” is the measurement of the human body with a view to determining characteristics such as the average dimensions and so on). Let us leave aside for the moment the question of what exactly the purported work of art is – is it the event itself or the resulting impressions of the models’ bodies? – and ask ourselves the obvious question. Rolling beautiful naked bodies in paint and pushing them against giant pieces of paper while dressed in a dinner jacket sounds marvellously good fun, but is it art? Indeed, we can polarize the debate. Let us call those who think that this is not art but some kind of elaborate con that has now been going on for far too long “traditionalists”, and those who think that Klein’s work is art, “radicals”.

If two people are faced with an object and one says it is not a camel and the other says it is a camel, they will be able to sort out their disagreement only if they both know what a camel is. Similarly, we will be able to sort out the disagreement between traditionalists and radicals only if we are clear as to the nature of the disagreement. In short, before we can make any progress on whether Klein’s work is art we need to work out what it is for an object to be a work of art. The traditionalist thinks he or she knows what art is, and is pretty sure Klein’s work is not art. The radical also thinks he or she knows what art is, and is pretty sure Klein’s work is art. It looks as if we have an unproductive stand-off.

The Cambridge philosopher Frank Ramsey held that it is a good rule of thumb that, in the face of apparently intractable arguments, one should look to see if there is something on which both sides agree that might be false. The obvious thing on which both sides agree in our case is that there is only one clear definition of “art”. Where they differ is that each thinks they have the correct definition and the other side does not. The traditionalist thinks that art is something like this: it takes skill to produce, it has to be worthwhile to experience, it has to be beautiful, and (possibly) it has to look like something. The radical will probably grant that what the traditionalist thinks is art is in fact art, but argue for a much broader definition: that something can be art if it challenges us, if it extends the boundaries of art or, at the limit, if someone who is an artist says that it is art. It is no wonder they do not agree. It would be as if one side of the argument said that a camel was a beast of burden that had humps for storing water and the other side said that while that was true, being a camel also encompassed anything that had wheels.

Who, then, is right – the traditionalist or the radical? How are we going to answer this question? One thing is clear: neither side is simply allowed to make definitions up. The person who believes that anything that has wheels is a camel is wrong. Such a definition would do nothing to clarify our thoughts about camels. So how do we find out what the word “art” means? Where do we get our definition of “art” from? Perhaps surprisingly, when we start to probe the answer to this question we find that the presupposition on which the traditionalist and the radical agree is indeed suspect: it is not obvious that there is only one clear definition of “art”. To see this, we need to take a good look at both definitions, in particular, the circumstances in which the traditionalist’s and the radical’s concepts of art arose.

The traditionalist’s concept of art is basically the concept of “fine art”, which encompasses music, poetry, painting, sculpture and dance. Some other art forms, particularly architecture, are somewhere on the margins and literature (as I mentioned in the Introduction) is best left to one side. In the 1950s, the formidable art historian Paul Kristeller argued that the concept of the fine arts had not always been with us but in fact is a fairly recent innovation. Hence, it is not like concepts such as “person” and “object”, which have, I suppose, been around since we could first think, and more like concepts such as “death certificate” and “human resources development manager”, which turned up when the time was right for them to turn up, and will fade away if we no longer need them. Kristeller surveyed a vast amount of writing on the arts from the past and came up with some surprising conclusions. The ancients, he says, “left no systems or elaborate concepts of an aesthetic nature, but merely a number of scattered notions and suggestions” (Kristeller 1951: 506). In medieval times, “the fine arts are not grouped together or singled out … but scattered among various sciences, crafts, and other human activities of a quite disparate nature” (ibid.: 509). It is only in the eighteenth century (1746, to be precise) that a French philosopher, Charles Batteaux, finally gave us the grouping that the traditionalist favours today (Kristeller 1952: 20). He listed music, poetry, painting, sculpture and dance together, claiming that they all evoked pleasure and also all imitated beautiful nature.

As a definition this needs some work. Let us start with the notion of “evoking pleasure”. This is undoubtedly part of the rewards of art: it is enjoyable to look at paintings or listen to music. “Pleasure” and “enjoyment” are words that cover a wide variety of cases, however. Activities such as sitting in the sun or chewing a toffee give us pleasure, but is that the same kind of pleasure that we get from a work of art? It might be the same for some art, but if all we took from art was the same as that which we took from sitting in the sun or sucking toffees then it would be difficult to see why we think art more valuable than sitting in the sun or sucking toffees. I am not going to argue that art is more valuable here; I shall say some more about that matter in the next chapter. What I want to do here is allow for the possibility that some works of art provoke states of mind that go beyond these simple pleasures. The term that is generally used here to describe those states of mind is “the aesthetic experience”.

What exactly counts as an aesthetic experience has been much discussed without that discussion resulting in any very precise conclusion. According to Baumgarten, it is the experience of beauty. It would not be very helpful for us to take this as a definition because, when we ask what “beauty” is, the obvious answer is that it is whatever it is that provokes the aesthetic experience; the two terms are defined in terms of each other. However, we are not left totally without resources for a definition. We can take the aesthetic experience to be a particularly valuable form of pleasure: value that does not only involve our feelings but also involves our minds. Looking at art (at least, looking at worthwhile art) is not a simple pleasure like sitting in the sun or sucking a toffee, but is an experience that involves thinking, feeling free from the humdrum concerns of everyday existence, and other such worthwhile satisfactions (Beardsley 1982).

The second clause of the definition concerns “imitating beautiful nature”. This might seem unduly restrictive. After all, “imitating beautiful nature” does not apply across the disciplines Batteaux listed. There is very little music that imitates nature, and it often sounds a bit silly when it tries (on the other hand, an extreme traditionalist might want painting to imitate nature in the sense that paintings ought to look like what they are paintings of). However, we weaken the definition significantly if we drop the second clause, for doing so would leave us unable to distinguish between art and nature. The first clause of our purported definition would include many natural objects because there are flowers, birds and landscapes that provoke the aesthetic experience. These are excluded from the definition by the second clause because these things do not imitate beautiful nature: they are beautiful nature. The most plausible way out of these problems is to find another way of excluding nature. We could say that a work of art was something that was made with the intention that it should provide an aesthetic experience (this is similar to the definition offered in Beardsley 2004). This would exclude nature because nature was not made by anyone and so not intended to be a certain way by anyone.

Drawing all this together, we get the thought that the concept of art that we inherit from the eighteenth century, which is the traditionalist’s concept of art, is that works of art are those objects which are made with the intention that they provide an aesthetic experience. Given this definition, the traditionalist will reject much of the art of the past one hundred or so years because much of this work was clearly not made with the intention of providing an aesthetic experience. Included among these will be some of the controversial works of modern art: the urinal signed and exhibited by Marcel Duchamp as Fountain (1917); Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966; a number of fire bricks laid out horizontally on the floor); and contemporary examples such as Jake and Dinos Chapman’s mutilated mannequins of children. These do not fall under the traditionalist’s definition and therefore, according to the traditionalist, are not art. That is, the traditionalist can happily keep the definition narrow; if it excludes some things that other people call “art”, then so much the worse for those things and those people.

Although narrow in some respects, the traditionalist’s definition looks too wide in others. There are plenty of things that appear to be intended to provide an aesthetic experience that nobody thinks are art. Indeed, most things that are made for human beings to use are designed to provide some kind of aesthetic experience, from Dualit toasters to Ducati motorbikes. If this is right, then all products of good design would seem to be art by the traditionalist’s definition. How could the traditionalist reply to this? One option would be to bite the bullet; to allow that all products of good design are art. After all, it is easy to imagine our admiring a beautiful motorbike and saying “that is a work of art”. This, however, seems a desperate measure. We do say of motorbikes that they are works of art, but we also say this of cakes and pantomime costumes. In such cases we do not mean that these things are literally works of art; rather, we are using the word metaphorically or as hyperbolic praise (as we might call a favourite niece “a princess” or a worthy neighbour “a giant among men”). If the traditionalist allowed in all products of good design their definition would be very wide indeed. A second option would be to change the definition so that works of art are objects where the primary intention is to provoke an aesthetic experience. The primary intention behind toasters is to toast, and that behind motorbikes is to get from one place to another. Hence, by this revised definition, they would not count as art. This might help exclude some things but not others. The appearance of a toaster is not intended to toast and various bits of a motorbike have little or no engineering function. Would those things be art? Also, this revision looks in danger of making the definition too narrow: architecture would cease to be an art as the primary intention behind buildings is not that they provoke an aesthetic experience. A third option would be to refine the notion of the aesthetic experience to capture only those states of mind provoked by what we pre-theoretically think of as art, and not what we pre-theoretically think of as design. That seems even more desperate; is the state of mind of looking at a beautiful work a different kind of state of mind from that of looking at a beautiful piece of design?

Let us put aside until later this problem for the traditionalist’s theory. It is easy to see that anyone who has this definition is going to be suspicious of Yves Klein’s work. It seems like a joke: in what way does Klein’s work belong to the category that includes such pieces as Mozart’s Requiem, Rembrandt’s The Night Watch and Michelangelo’s David? Listening to a piece of music that is simply a single note for twenty minutes does not provide an aesthetic experience; it simply exasperates. Furthermore, what aesthetic reward is to be taken from seeing the impression of a paint-smeared human body on paper, which is, after all, only a larger scale version of finger-painting?

The key question, which throws light on the dispute between traditionalist and radical, is that if the concept of art can be “invented” once, why can’t it be “invented” twice? It was not an accident that the traditionalist concept of art appeared when it did; that great upheaval in human thought, the Enlightenment, was in full swing. It was as if people had suddenly rediscovered leisure and intellectual enquiry; the arts and philosophy were flourishing, and the first novels (by Defoe and Richardson) had all been published within thirty years of Batteaux’ grouping. The prevailing cultural mood was ripe for just such conceptual innovation. Simplifying somewhat, there was leisure time to be had, so there was space for the notion of something to be enjoyed simply for the sake of enjoying it. The key point, and the clue as to why we might have more than one concept of art, is that the Enlightenment has not been the only great upheaval in human thought. There has been another more recently, and it goes under the name “modernism”.

In the visual arts, modernism is usually taken to start around the 1860s with the work of Manet. There is some dispute about when it ends, but the majority view is sometime in the 1960s. Let us begin with a plausible story. The end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth saw huge social and political change: there was mass industrialization, the rise of a self-conscious working class, wars in Europe, the shattering of social mores and much else besides. Virginia Woolf remarked (with some exaggeration) that “on or about December 1910 human character changed” (Woolf 1924). Art, or at least the visual arts, were under pressure from two sides. First, as had happened in the eighteenth century, art was not immune from the rest of society; it needed to respond to events. Second, there was a more particular concern. According to Batteaux, as we have seen, part of what makes the arts arts is that they “imitate beautiful nature”: one of the functions of paintings is to capture the way the world looks. The Night Watch captured the appearance of the night watch. The more particular concern was that this function was now being taken over by seemingly more efficient and accurate technologies. The first mass-produced camera – the Kodak Brownie – was marketed in 1900, and the Lumière brothers started projecting films in 1895. Art, or at least visual art, had lost the role Batteaux had found for it.

According to at least one form of modernism, this crisis of confidence in the arts brought with it its own solution. Deprived of the role of capturing the way the world looked, art was forced to look in on itself: to conduct a thorough investigation of its own nature. In the words of the distinguished modernist theorist Clement Greenberg, “The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence” (Greenberg 1992: 308). Before the end of the nineteenth century, art had explored its nature as something that captured appearances and could be enjoyed for its own sake. However, now the search needed to broaden; the content of art, what individual works of art were about, was the nature of art itself. In 1748, Batteaux had given us the traditionalist concept of art; in or around 1914, artists such as Marcel Duchamp gave us a different concept of art – the modernist concept of art.

What is this concept? Batteaux, as we have seen, gave us a two-pronged definition: art could be enjoyed for its own sake and imitated beautiful nature. What is the modernist definition? Let us jump forwards fifty years and consider a famous work of art that became a famous philosophical example: Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964). A Brillo box (that is, the “mere real thing” not the work of art) is a plywood box with a design on it that was used to store and transport Brillo Pads (a household cleaning product). Warhol made some plywood boxes to the exact size and screenprinted the designs on the side. What he produced were boxes that were visually indistinguishable from the mere real thing.

When the philosopher Arthur Danto saw these exhibited at the Stable Gallery in New York he had a revelation. Here were objects that were art that were visually indiscernible from objects that were not art. This prompted him to ask the question: what is it for the one set of objects to be art and the other set of objects not to be art? If we had asked the question of a traditional work of art, the answer would have been ...