eBook - ePub

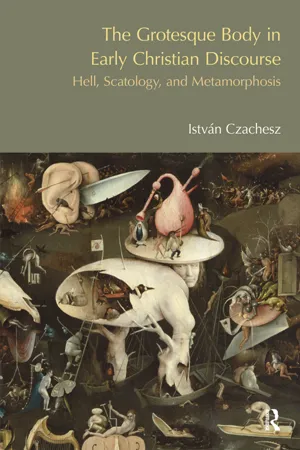

The Grotesque Body in Early Christian Discourse

Hell, Scatology and Metamorphosis

This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Early Christian apocryphal and conical documents present us with grotesque images of the human body, often combining the playful and humorous with the repulsive, and fearful. First to third century Christian literature was shaped by the discourse around and imagery of the human body. This study analyses how the iconography of bodily cruelty and visceral morality was produced and refined from the very start of Christian history. The sources range across Greek comedy, Roman and Jewish demonology, and metamorphosis traditions. The study reveals how these images originated, were adopted, and were shaped to the service of a doctrinally and psychologically persuasive Christian message.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Grotesque Body in Early Christian Discourse by Istvan Czachesz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

HELL

Chapter 1

GROTESQUE BODIES IN THE CHRISTIAN UNDERWORLD

“Didymon the flute-player, on being convicted of adultery, was hanged by his namesake.” This ancient Greek joke is quoted as an example of a chreia in Aelius Theon’s Progymnasmata.1 It makes use of at least two correspondences. On one hand, two different meanings of the word δíδuμoς are involved. First, it is the flute player’s name, meaning “twin brother” (as with Jesus’ disciple “Thomas called Didymus”);2 the second half of the joke evokes the plural of the word in the meaning of “testicles.”3 On the other hand, the flute player’s punishment corresponds to the sin that he committed. Beyond these primary and obvious sources of humor, the anecdote implies several other levels of meaning. For example, it can be interpreted in the framework of widespread associations of flute players with gaiety: “[aulos] was an instrument that produced bawdy music and deformed the face and so was not proper for free women, or even citizen men. Plato (Republic I.399d) banned it from his ideal city, and according to Aristotle (Politics 1341), citizens could listen to it, but should not learn to play it for it was not considered a ‘moral’ instrument.”4 Our text adds an unexpected twist to the popular image of flute players: whereas in most literary references they appear as instruments or objects of ecstasy and lust,5 the Didymon joke characterizes its protagonist as the originator of sexual transgression. Thus the text confirms as well as generates prejudice.

The point involved in the punishment itself, the comical position of hanging upside down from one’s testicles, affects the listener in a different way. Whereas the puns and intertextual references generate satisfaction, the indication of the punishment brings about a certain ambivalent inconvenience, rather than relief. Although it can be seen as humorous, it is better called grotesque. The image of the human body evoked in the joke is surprising, distorted, and disturbing.6

The sorrowful fate of Didymon is not unparalleled in Jewish and Christian literature, where it normally belongs to the scenario of hell. In Jewish Apocalypses, men and women are often hanged by their genitals or nipples.7 In these sources, however, the punishment is meant dead earnest rather than humorous. Hanging by the genitals also appears as a punishment for adultery in the underworld of Lucian’s True Story. Cinyras, one of Lucian’s traveling companions, abducts the wife of another member of the crew. The adulterer is whipped with mallow, bound by the genitals, and taken off to the abode of the wicked, where he is later seen “wreathed in smoke and suspended by the testicles.”8 Comparing the occurrences of the same motif in Lucian’s hell and the Jewish Apocalypses shows that whereas the former exploited the humorous aspects of grotesque body images, the latter used them to horrify the readers.

A similar punishment is found in the first Christian description of hell, which is contained in the Apocalypse of Peter (ApPt), where it occurs in the euphemistic variant of “hanged by the feet” (Ethiopic: “thighs”).9 This punishment is far from being the only example of grotesque imagery in the ApPt. In this early Christian apocalyptic source, images of the grotesque body fill the infernal landscape. In this chapter, I will undertake a literary analysis of the grotesque body in the ApPt, asking about the connection between sins and punishments, the relation of the punishments with each other and the overall structure of hell, as well as the relation of the description of hell to the narrative frame of the text. In Chapter 2, I will return to this writing as I investigate the sources of the punishments in the ApPt and the Apocalypse of Paul (Visio Pauli), including the question of whether they can reflect the actual sufferings of Christians, or punishments used otherwise in the ancient world.

Sins and Punishments

The Apocalypse of Peter was written in the first half of the second century.10 The text has been preserved in two different versions: the Greek text of the Apocalypse was excavated in Upper Egypt in 1886–87, near the city of Akhmim;11 the Ethiopic text, which is longer than the Greek, was published in 1910 and soon thereafter identified as a witness of the Apocalypse of Peter.12 For the interpretation of the text I will proceed from the longer version, following the practice of contemporary scholarship.13

The narrative frame, constituting the first major division of the extant text of the ApPt, is contained in the Ethiopic text (E).14 On the Mount of Olives, the disciples approach Jesus and ask him to tell them about the signs of the last days and the end of the world. Most of Jesus’ answer (chs 1–2 E) echoes eschatological passages from Matthew 24.15 In the next part of the Ethiopic text (chs 3–6 E), Jesus shows Peter “in his right hand…and on the palm of his right” everything that shall be fulfilled on the last day: resurrection, Jesus’ coming with glory on the clouds, and the final judgment. This is followed by the second main unit, dealing with sins and punishments. In this part of the book, the Ethiopic (chs 7–13 E) and the Akhmim text (chs 31–4 A) run basically in parallel, the Ethiopic version being somewhat longer. The third main unit deals with the fate of the righteous, largely resembling the synoptic transfiguration scene.16 This section is found at the end of the Ethiopic version (chs 14–7 E), but it is placed before the description of hell in the Akhmim text (chs 1–20 A).

After this quick overview of the composition of the extant parts of the book, let us take stock of the sins and punishments found in the ApPt.17

First of all, we can observe that the punishments of the ApPt present a distorted picture of the whole body. The head is in the mud; hair is used to hang up women by it; eyes are burned; there is a burning flame in the mouth; people bite their tongues and are hanged up by them. Innards are eaten by worms; flames burn people waist-high; men are hanged up by their thighs – a euphemism for genitals.18 Legs are also involved when the rich ones dance on sharp pebbles. The whole body is dressed in rags, roasted on flames, and often hanged upside down. These images can be compared with the appearance of the righteous (as well as of Moses and Elijah in the Akhmim text), where many of the body parts (hair, faces, shoulders, also clothing) are described as beautiful and harmonic (6–20 A; 15–6 E). The beautiful bodies of the saints are contrasted with the distorted bodies of the condemned.

Sin | Punishment |

Blaspheming the way of righteousness. (22 A; 7.1–2 E) | Hanged from the tongue, fire. |

Turning away from righteousness. (23; 7.3–4) | Pool of burning mud. |

Women who beautified themselves for adultery. (24a; 7.5–6) | Hanged from the hair over bubbling mud. |

Men who committed adultery with those women. (24b; 7.7–8) | Hanged from the legs, head in the mud, crying, “We did not believe that we would come to this place” |

Murderers and their accessaries. (25; 7.9–11) | Tormented by reptiles and insects, their victims watching them and saying, “O God, righteous is thy judgment.” |

Women who conceived children outside marriage19 and procured abortion. (26; 8.1–4) | Sit in a pool of discharge and excrement, with eyes burned by flames coming from their children. |

Infanticide. (8.5–10 E) | Flesh-eating animals come forth from the mothers’ rotten milk and torment the parents. |

Persecuting and giving over the righteous ones. (27; 9.1–2) | Sit in a dark place, burned waist-high, tortured by evil spirits, innards eaten by worms. |

Blaspheming and speaking ill of the way of righteousness. (28; 9.3) | Biting one’s lips, getting fiery rods in the eyes. |

False witnesses. (29; 9.4) | Biting one’s tongue, having burning flames in the mouth. |

Those who trusted their riches, did not have mercy on the orphans and widows, and were ignorant of God’s commandments. (30; 9.5–7) | Wearing rags and driven (dancing) on sharp and fiery stones. |

Lending money and taking interest on the interest. (31; 10.1) | Standing in a pool of blood, pus and bubbling mud. |

Men behaving like women, women having intercourse with each other. (32; 10.2–4)20 | Endlessly throwing themselves into an abyss. |

Those who made idols in place of God. (33a; 10.5–6) | Standing in a place filled with great fire. |

??? (33b A)21 | Man and women hitting each other with fiery rods. |

Those who abandoned the ways of God. (34; 10.7) | Burned, turned around and roasted. |

Those who did not obey their parents. (11.1–5 E) | Slip down from a fiery place repeatedly.22 Hanged and tormented by flesh-eating birds. |

The whole body is at the same time dissected. As the Ethiopic text writes of the fallen maidens, “Their flesh will be torn in pieces.” Whereas hell is described as a horrendous place in general, and the entire body is subjected to punishment, most of the time, typically by immersion or hanging, we can also observe a focus on particular members of the body in each case. Can we identify an underlying logic that determines how different sins are connected to particular punishments and body parts? According to the most widespread view, the underlying logic of sins and punishments in the ApPt can be compared to the law of retribution (lex talionis) in the Torah.23 The famous principle of talion is read in Exodus 21: “You are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, bruise for bruise.”24 However, if we take a closer look at the tortures, we find that the order of sins and punishment in the ApPt is similar to but not quite identical with the lex talionis. The principle of measure for measure retribution is realized in its proper sense only in two cases in the ApPt: (1) the persecutors of Christianity are burned on fire and eaten by worms; (2) victims are watching their murderers being eaten by reptiles and insects. Even in these passages some interpretation is required to clearly identify the principle of talion.

It is possible to tweak the principle of talion so that it explains more sins and punishments in the text.25 In a more general sense, the principle of talion means that some punishment is fitting the crime or commensurate with it. Yet the logic of the ApPt seems to be more rigid and not too concerned with actual legal hermeneutics. As it explains so little in our text, it is better to abandon the concept of talion altogether. Instead of proceeding from the eye-for-an-eye principle of the Pentateuch (and other ancient traditions), I suggest that the punishments of the ApPt follow a principle that is formulated in a well-known passage of the Sermon on the Mount (Mt. 5:29–30):

If your right eye causes you to sin, gouge it out and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of body than for your whole body to go into hell.

The concept behind this utterance is that certain crimes are committed by certain parts of the body. The idea occurs also in rabbinical Judaism: “Those bodily members which commit transgression are ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I – Hell

- Part II – Scatology

- Part III – Metamorphoses

- Bibliography

- Index of Ancient References

- Index of Authors

- Index of Subjects