eBook - ePub

Inclusive Design

Implementation and Evaluation

- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inclusive Design

Implementation and Evaluation

About this book

As part of the PocketArchitecture Series, this volume focuses on inclusive design and its allied fields—ergonomics, accessibility, and participatory design. This book aims for the direct application of inclusive design concepts and technical information into architectural and interior design practices, construction, facilities management, and property development. A central goal is to illustrate the aesthetic, experiential, qualitative, and economic consequences of design decisions and methods. The book is intended to be a 'first-source' reference—at the desk or in the field—for design professionals, contractors and builders, developers, and building owners.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

chapter 1

Pre-design

Pre-design, the stage when funding is available and before design begins, is a crucial phase for those in inclusive building practices. While typical pre-design focuses on project vision and goals, programming, site and building analyses, project cost and feasibility, and a review of planning and zoning regulations, inclusive design gives precedence to some of these areas over others. In addition to standard practices, inclusive pre-design involves establishing a diverse project team and making certain that clients and neighborhood communities collaborate with the design team, especially in the planning process. As well, an inclusive designer will spend more time discussing with the client the needs of everyone who will use the space; these include current as well as future needs that engage a wider range of people and circumstances. Furthermore, inclusive designers will devote considerable attention to site and space analysis to ensure ease of site access, seamless circulation, and entry. Focusing on this up front usually results in more integrative solutions that are less expensive. Finally, the environmental, social, political, technological, and economic conditions related to each project require extra planning to guarantee not only inclusive results, but inclusive processes as well. This early investment brings about improved building quality, reduced operational costs, and increased satisfaction among the stakeholders over the life span of the building.

Strategy 1.1 Getting started

At the start of a project, explore and define four elements: (1) the makeup of the project team, (2) the range of potential users and stakeholders and their relationships to one another, (3) the research and site analyses that are most important, and (4) the contextual, yet potentially hidden, factors that might facilitate or impede success.

Who are the stakeholders, what are their roles, and how can they be organized?

Financiers

The financiers of building projects vary depending on the scale and type of development. This group can consist of sponsors; lenders; financial, technical, and legal advisors; equity investors; regulatory agencies; and multilateral agencies. Their primary role is to develop a preliminary assessment of funding options to determine the viability and risks of a project. This assessment most often includes budget, draw-down facilities, approvals and consents, taxes, grants, loan size and term, land value, building costs, end-valuation, stage payments, planning risks, profit on cost, and collateral. Financiers who are backing an inclusively designed project need to clearly understand its vision and goals, how the building will perform differently from conventional buildings, and understand the financial implications of the inclusive design process (i.e., where investments need to be increased, where costs can be saved, and the long-range value of utilizing inclusive design principles).

Building owners and developers

Inclusive design provides building owners and developers with ways to maximize their buildings’ responsiveness to an increasingly diverse marketplace. Buildings that are not usable by everyone are becoming more marginalized and, consequently, tend to lose their relative value. Inclusive design has become a cost-effective strategy for maintaining or even enhancing the profitability of building inventories.

Building construction, renovation, and maintenance costs are more readily justified when all people benefit. Consequently, building owners and managers, who embrace the goals of inclusive design, are less likely to see their decision making during construction, renovation, and maintenance projects become the targets of “penny wise and pound foolish” criticisms following their completion.

Architects

Inclusive design is a rapidly expanding area of practice in architecture. The growing need to design buildings that are usable by everyone regardless of their intellectual, functional, or sensory abilities is a demographic fact of life. Inclusive architects contribute to the socially and ethically responsible design of buildings. They promote replacement of discriminatory exclusive designs with affirming inclusive designs. They understand life cycle requirements and work to enhance the quality of life for every individual through high-performing and aesthetically pleasing spaces that are affordable for all. And, inclusive architects do this without prescriptive standards that might stifle creativity. The benefits of inclusive design are best achieved by reinforcing design innovation rather than design imitation.

General contractors and construction managers

Inclusive design guidelines can help contractors and construction managers develop efficient strategies for responding to both short-term and longer-term conditions encountered during the construction process. More important, the examples and guidelines provide a broad understanding of how application of the principles of inclusive design at a construction site can ensure the realization of a building that is truly usable by everyone – and, typically, at a cost that is competitive with conventional design and construction methods. Contractors and construction managers require specialized knowledge of inclusive construction practices such as how to install French drains at no-step entrances and dropped shower floor pans in roll-in showers. They are responsible for ensuring that the infrastructure for future inclusive features (e.g., blocking for grab bars and stacked closets with reinforced walls for eventual elevators) is included as part of standard building construction.

Facility managers

A well-functioning built environment requires integration of people, places, processes, and technology. Inclusive integration of these elements necessitates a deeper understanding of the potential ways that marginalized groups interact with the environment. While all facility managers organize and oversee buildings and their premises, inclusive practitioners place special focus on human factors; multisensory communication; emergency preparedness for all occupants, especially those with disabilities; accessible space planning; environmental health and safety; and administering essential inclusive services (reception, security, maintenance, cleaning, recycling, etc.). Their management at both the strategic planning and day-to-day operation levels requires specific goals developed in concert with building occupants followed by regular evaluation of progress.

Above all, inclusive facility managers need to consider lasting solutions to complex problems even though they might take longer to develop. Anticipating the unintended consequences of building operations requires input from all people who use the building; that way, causes of problems are favored over treating mere symptoms.

Building servicers

Most building servicers are responsible for the installation, management, and monitoring of the systems required for the safe, comfortable, and sustainable operation of buildings. Inclusive servicers differ in that they seek regular feedback from building superintendents and occupants to ensure that the integrated systems are working smoothly at all times. In addition, they use inclusive design principles and goals both to determine the best systems and recurrently evaluate them once installed. Comfortable spaces and temperature, clean air, ample lighting, efficient communication and power capabilities, high-quality sanitation, accessible pathways and vertical circulation, and protection of life and property are the primary foci of inclusive servicers.

Clients

Regardless of whether clients are purchasing office buildings or a single-family home, they want to customize spaces to meet current and future needs. The spatial configurations, features, materials, and products they choose can further this goal. Understanding the principles and goals of inclusive design can help clients make thoughtful decisions that accommodate occupants’ changing requirements. Educated clients purchase inclusively designed elements that are integrated and virtually invisible. An essential part of their charge involves in-depth planning that considers all potential users and uses for the space. This calls for more work up front, but raises the quality of choices and, thus, the performance and efficiency of the built environment.

End users

Inclusive living is the responsibility of all who are part of a building’s life cycle. End users play a critical role in ensuring the best possible environment. However, to actively participate, most need education in inclusive design practices. Occupants require accurate, up-to-date information on the benefits of inclusive living, including aspects for which they have direct control such as placement of freestanding furniture, task lighting, and handheld objects; elimination of toxic chemicals and allergens; and setup of multisensory functions on communication devices. Empowering end users by making them aware of specific actions they can take to improve the functions of the building provides consistent, on-site attention. As part of the team who reports building-related inclusive design inefficiencies to building management, occupants assume stewardship of their environment.

How does research in preparation for an inclusive project differ from traditional research processes?

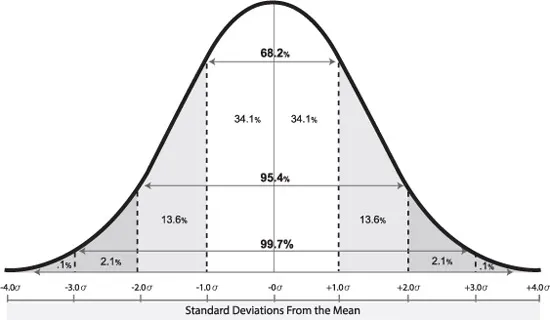

Research is an integral part of any design process. Evidence-based design is a growing field in planning, the design professions, and construction, where credible research is used to influence design decisions. Designers, builders, and developers use available information from a variety of resources, including precedent studies, user input, project evaluations, and targeted research studies to improve efficacy and performance outcomes such as safety, usability, and cost. Evidence-based design has become commonplace for health care facilities and other projects that tend to be high in cost, that require specialized knowledge and consultants, and where design oversights possess catastrophic consequences. When preparing for any project, at minimum, research needs to incorporate findings from similar projects and include data on the specific users of the building. For an inclusive project, research must also include data from diverse stakeholder groups; a successful inclusive project gathers information on a wide spectrum of users, including those individuals at the extremes of the “bell curve.”

Anthropometric dimensions taken from a large enough population will distribute themselves in a normal distribution or bell curve (see Figure 1.1). Most people will fall in the middle part of the curve (within two standard deviations from the mean), with very few at either of the extremes. The rationale for not accommodating everyone’s needs in a design project is usually that it is not cost effective to do so because most people will fall in the middle part of the curve; clearly, this general rule does not address the Goals of Universal Design. The first objective of any design project should be to try and accommodate everyone. When design for the extremes is not feasible, a more realistic target is addressing the needs of the 5th–95th percentiles. When it is apparent that some people will have to be excluded, the 5th–95th rule can be applied to the population group that is most likely to be excluded by a design. For example, enough space can be allocated to accommodate the 95th percentile of maneuvering abilities for wheeled mobility device users. If their needs are met, it is likely that all ambulatory individuals will have enough space as well.1

1.1 Normal distribution bell curve

Rarely does an individual fit within the same range for every characteristic or ability. A person with a long trunk may have short arms, or a person with short stature may have large hands. Since two different dimensions taken from the same person may represent different percentile values within the population, there is no such thing as a person who can serve as a model user for the 5th or 95th percentile. Each design has to be addressed separately using research data on the related anthropometric parameter from a representative sample of the end user population, if that information is available.

Precedent studies

When embarking on a new project, designers, builders, and other stakeholders may benefit from researching and referencing precedents. Precedent studies are earlier occurrences of similar projects that can serve as examples for guiding design decisions. For example, they can help identify both successful and unsuccessful strategies that can be applied or avoided in a new project. Using precedent studies lends authority to a specific design and offers an opportunity to communicate potential designs to key stakeholders. The ability to demonstrate the construction practices, materials, or style from an existing project allows stakeholders such as investors, clients, and end users the ability to more accurately understand a project. When selecting an appropriate precedent study, it is important to understand the current design problem and select a suitable model that addresses a similar problem. Wherever possible, it is also important to utilize precedents that successfully incorporate the needs and wants of diverse groups and support desirable performance outcomes. UDNY, UDNY2, The Universal Design Handbook, Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments, The Inclusive City, and so forth are just a few of the resources that provide precedents for housing, commercial building, transportation, and product-related projects that incorporate the needs of a variety of end users. Despite the benefits of referencing precedents, it remains important to acknowledge that sometimes breaking with precedents leads to innovative solutions that may benefit everyone.

In contrast to precedent studies, case studies offer in-depth investigations of a specific topic that describes and/or evaluates a real-life project or process. Case studies typically bring to light exemplary projects and concepts worthy of replication or broader dissemination. They often serve to formalize what are typically generalizations or anecdotal information about projects and processes.

User input: survey, focus groups, etc.

A critical aspect of research in pre-design is to learn from the people who will use, visit, and manage the building/site. The aim is to support and enhance their independence, productivity, and satisfaction. Gathering user input can occur using a variety of research methods, such as observations, focus groups, surveys, and interviews. Each method offers advantages and disadvantages in gaining information and perspectives.

Strategy 1.2 Gathering useful information

Utilize multiple sources of information and leverage an array of methods for gathering it, including observation, focus groups, surveys, and interviews of clients, occupants, and other stakeholders.

Observations are a helpful first step in data gathering because they provide useful information on how occupants interact with one another and the built environment in their existing setting. More specifically, direct observations enable the designer to understand both who is using the space and how they are using it, including patterns and anomalies of activity, individual preferences and needs, and high- and low-functioning spaces and features. Oftentimes, users are unable to describe their needs and/or requirements when they are asked. Observations allow designers to gather more information than they might otherwise have if they simply just interviewed users. Whereas users may be non-forthcoming in interviews or focus groups, observations allow designers to see users perform activities in a natural setting. Thus, designers...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Series editor’s preface

- Authors’ preface: practicing inclusive design

- An introduction to inclusive design

- Chapter 1 Pre-design

- Chapter 2 Design

- Chapter 3 Construction

- Chapter 4 Occupancy

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Inclusive Design by Jordana L. Maisel,Edward Steinfeld,Megan Basnak,Korydon Smith,M. Beth Tauke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.