eBook - ePub

State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle

Thomas B. Gold

This is a test

Share book

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle

Thomas B. Gold

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Explores the application of constructivist theory to international relations. The text examines the relevance of constructivism for empirical research, focusing on some of the key issues of contemporary international politics: ethnic and national identity; gender; and political economy.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle by Thomas B. Gold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Estudios étnicos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Explaining the Taiwan Miracle

In November 1977, two months after I arrived in Taiwan to do the research for this book, the island experienced its first outbreak of popular antigovernment violence in thirty years. Fed up with the ruling Nationalist party’s repeated crude attempts to rig the election for magistrate of T’ao-yuan County, a crowd of 10,000 people attacked the police station in the town of Chung-li, burned a police van, and went on a rampage.

This event was extraordinary for two reasons: one, that in Taiwan, a newly industrializing society noted for its strict authoritarianism and politically apathetic populace, a segment of the people had resorted to such an extreme and risky act to vent its frustration; and two, that a rapidly developing society had been free of social and political upheaval for such a long time.

In retrospect, the Chung-li Incident offers a unique key to understanding both the success and the shortcomings of Taiwan’s development strategy wherein a strong authoritarian state guides and participates in rapid economic growth while suppressing the political activities of the social forces it has generated in the process. Chung-li represents the culmination of one historical stage in the interaction of these two strains and the beginning of a new one.

Departing from the standard economistic approach commonly used to explain Taiwan’s economic miracle, this book offers a comprehensive sociological analysis, explaining Taiwan’s unquestioned success by reference to the internal and external social, political, and economic contexts in which it occurred.

The Statistics on Taiwan’s Miracle

The data on Taiwan’s developmental experience up to 1982 are voluminous and can be accurately summed up with the government’s own maxim, “growth with stability.”

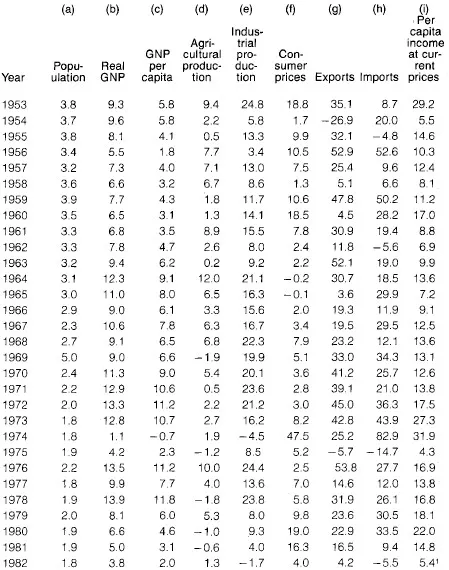

On the economic side, where development refers not only to GNP growth rates but also to structural change and deepening of industrialization, table 1 shows that

—GNP growth rates averaged 8.7 percent from 1953 to 1982, with a peak average of 10.8 percent for the years 1963–1972 (TSDB 1983:2). The 1982 value of GNP was twelve times that of 1952 (TSDB 1983:1).

—Industry grew at a spectacular rate, an average annual clip of 13.3 percent from 1953 to 1982 (TSDB 1983:2) to 42 times its 1952 value (TSDB 1983:1).

—The economy underwent a noticeable structural change as the contribution of industry outstripped agriculture and the leading sectors of industry changed as well, from processed food and textiles to electronics, machinery, and petrochemical intermediates. This indicates diversification and deepening of the economy.

—Trade surpluses occurred nearly every year since 1970 (TSDB 1983:184).

—Inflation was conquered, dropping from a murderous 3,000 percent in 1949 to 1.9 percent in the 1960s. Its resurgence has been regulated since the first oil crisis of 1974–75 (Kuo 1983:2).

—Gross Domestic Capital Formation has been financed almost entirely from gross domestic savings since the early 1960s (TSDB 1983:48).

—The gross savings rate has been above 20 percent of GNP every year since 1966 and more than 30 percent in ten of those years up through 1982 (TSDB 1983:49).

—Foreign reserves amounted to US $7 billion in 1980 (Prybyla 1980:75) and $15.7 billion at the end of August 1984 (FEER, October 4, 1984:72).

—Debt-service was a remarkably low 4.4 percent of exports in 1978 (World Bank 1980:135).

—The government showed budget surpluses every year from 1964 through 1981 (TSDB 1983:151).

On the social side, where development refers to changes in the occupational structure and per capita income as well as a host of indices denoting improved physical and abstract quality of life, table 1 indicates

—A positive record of equitable income distribution, with GINI coefficients1 decreasing from .558 in 1953 to .303 in 1980 (Kuo 1983:96–97).

—Employment in the primary sector dropping from 56 percent in 1952 to 18.9 percent in 1982 and employment in manufacturing rising from 12.4 percent to 31.6 percent over the same years (TSDB 1983:16) with a negligible unemployment rate (TSDB 1983:14).

—Nine years of free compulsory education since 1968 and a literacy rate of 89.3 percent in 1979 (Hsi 1981:81).

—Other indicators of improved living standards, such as daily calorie supply of 2,805 per capita or 120 percent of requirement (World Bank 1980:153); infant mortality rate of 10.9 per thousand (HUDD 1981:57); life expectancy of seventy-two years (World Bank 1980:111); per capita income of US $1,229 in 1981 (HUDD 1981:7); 13.16 telephones per 100 people (HUDD 1981:51); and 212.3 television sets per 1,000 people (HUDD 1981:6).

—Domestic social and political tranquility from 1947 to the Chung-li Incident of 1977, including a smooth leadership transition after the death of long-time leader Chiang Kai-shek in 1975.

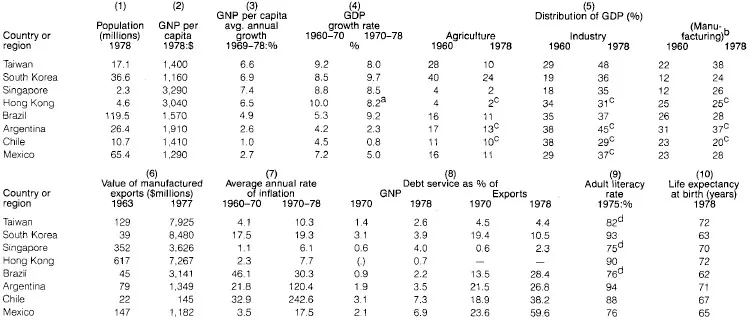

This is a remarkable record by any absolute or relative standard. The combination of economic and social development out of a morass of chaos and despair, compounded by one of the world’s highest population densities—512.6 persons per square kilometer in 1982 (TSDB 1983:5), a crushing defense burden, and a dearth of natural resources (most notably, oil), justifies calling Taiwan’s accomplishments a miracle. Table 2 illustrates Taiwan’s accomplishments from a comparative perspective.

Answered and Unanswered Questions

How do we explain Taiwan’s miraculous growth with stability? There are two questions to address: First, how did Taiwan attain and sustain such high economic growth rates? Second, how did Taiwan maintain political and social stability in the course of its economic takeoff?

Table 1

Indicators of Taiwan’s Economy 1953–1982

Unit: % of growth

Unit: % of growth

Source: Columns a-h, TSDB (1983:2); column i, TSDB (1983:29).

Note: 1. Estimate.

Table 2 Taiwan in Comparative Perspective

Source: World Bank 1980: Columns 1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 10:111, Column 4: 113, Column 5:115, Column 6:133, Column 8:135.

Notes: a: for 1970-77, b: manufacturing is part of the industrial sectors, c: for 1977, d: for years other than 1975.

Most scholars both on Taiwan and abroad address the first question.2 Some are seemingly most interested in reducing Taiwan’s developmental experience to mathematical equations; others explain it primarily as a case of getting the relationship between domestic and international prices right; and a few point out that the state is an active participant in the economy, not merely a maker of policies and externalities. The explanation offered by economists can be summarized as follows.

Fifty years of colonial occupation by the developmentalist Japanese left a legacy of very productive if skewed agriculture, an island-wide infrastructure of roads, power, communications, etc., and investment in human resources. The infrastructure and small modern industrial sector were virtually wiped out by American bombing in the last years of the Pacific War. When the Japanese suddenly departed in 1945, and especially as the Communists took over the Chinese mainland, talented and dedicated Western-oriented Chinese officials, technocrats and businessmen from the mainland, filled the leadership vacuum that the native Taiwanese, always treated as a second-class race by the Japanese, were unqualified to fill. The mainland emigré elite, motivated by the official ideology of the Three Principles of the People, rapidly revived production to prewar peaks while stabilizing the political situation. At a critical juncture, American military and civilian aid provided a buffer to help control inflation; rebuild the economy; supply needed commodities, raw materials, and foreign exchange; and generally boost the confidence of the government and people. The Nationalist Chinese government is committed to development and social welfare, but it favors free-market principles. It practices fiscal conservancy to balance the budget and prevent renewed inflation. It led the Land Reform, did not neglect agriculture, protected infant industries when necessary but then wisely took the difficult step of reorienting the economy to exports via trade liberalization, price reforms, and other incentives. It created a good business climate for local and foreign investors. Taiwan’s prime resource has been an abundant supply of cheap and disciplined labor, and the private sector and foreign corporations invested in labor-intensive rather than showcase capital-intensive industry, which helped to absorb labor and distribute income more equitably. Labor and other factor productivity grew rapidly. Taiwan used its comparative advantage in labor to compete successfully in world markets, and exports became the leading engine of growth. The people are by nature thrifty, hard-working, disciplined, and ambitious, and they place a high value on education.

This explanation covers the economic bases and goes a step beyond conventional neoclassical economic explanations by bringing the state in as an indispensable actor. It also leaves many unanswered but key questions, however, most of which relate to pinning down the reasons why Taiwan was so stable during this rapid economic takeoff. From what source, for example, did the Nationalist state derive its effective power? Why has it succeeded in bringing about development when other authoritarian states have failed and its own experience on the mainland was such a disaster? Has liberalization meant an end to state participation? How has it maintained social and political stability? What limits are there to the Nationalist state’s power?

In addition, what effect did Taiwan’s social structure have on development and vice versa? Why were workers, peasants, landlords, intellectuals, and the middle class so quiescent and cooperative? Have different social groups benefited disproportionately from Taiwan’s type of economic growth strategy? As the social structure changes, what effect are new social forces having on the direction of economic growth and continued stability? Why has there been an upsurge in political movements for democracy since 1971, and especially since 1977?

What role have global political and economic structures played in Taiwan’s development? Why did transnational corporations (TNC) invest in Taiwan and what was their impact on the economy and society beyond an infusion of capital and transfer of technology? Do TNCs from different countries behave differently and have different impacts?

In sum, although it goes beyond pure economistic explanations and brings in the role of the government, the standard economic approach does not delve further and ask how the structures and institutions that contributed to and shaped Taiwan’s growth were formed, maintained, and have evolved.

At the opposite extreme from the economists, there are a small number of scholars who analyze Taiwan from a dependency or world-systems perspective.3 As a rule, they start from outside Taiwan and situate it in global economic and political structures, first the Japanese empire, then the American-dominated modern world capitalist system. They attribute almost everything that has happened in Taiwan to external actors, denigrating the role of the Nationalist state and Taiwan’s people beyond serving and responding to foreign masters. Taiwan would be nothing without Japanese imperialism, the U.S. Army, Agency for International Development, transnational corporations, international banks, and so on, the argument runs. Capital, technology, and demand are all externally derived. In this view, the state in Taiwan is a tool of foreign corporations, repressing its people, especially the proletariat, in the service of superexploitative global capital. Local entrepreneurs are compradors who sell out to their foreign masters.

These writers start with a preconceived model that they try to make Taiwan fit into. When it doesn’t, they either reinterpret the facts to show that “so-called” development and equity are not really development and equity, or that Taiwan is an exception to all laws because of special circumstances. While they add a corrective to the narrow endogenous explanatory schema of the economists, drawing attention to social structure and exposing many of the costs of Taiwan’s development path, their unwillingness to seek truth from facts, their use of rigid categories, and their undisguised antipathy seriously limit the usefulness and credibility of their argument.4

Fewer scholars have looked into the reasons for Taiwan’s stability. The most common explanations focus on the declaration of martial law and the pervasive and multiform internal security system.5 In some cases, the stability is linked with the need to provide a stable investment environment for TNCs, but it is always tied to the Nationalist party’s overriding concern with preserving its power. The system is seen as frozen and inflexible from top to bottom. Other writers admit the authoritarian nature of the regime, but see the cause as much less sinister.6 Their approach to the matter of stability emphasizes Taiwan’s relatively equitable income distribution and mobility as defusing social tensions. For them, repression was necessary in the first instance to prevent communist subversion and mass revolt; the external threat is still quite real, so one-party rule and internal spying perform necessary functions. They see this not, however, as something inherent in the system, but as a stage already passing on the route to constitutional democracy. They accentuate the increased importance of electoral politics, emergence of an opposition, and recent democratization as proof. For them, the repressive apparatus performed a valuable function for stabilizing the society and helping to legitimize the regime, but current stability derives from shared interest among all social forces in preserving what they have built together, and from value consensus, especially anticommunism.

These analyses contain many valid points, but again they do not go far enough in exploring the connections among the repressive aspects, the social structure, economic growth, and external forces. Taiwan is hardly the only society under martial law—why has it been so effective and long lasting there and not elsewhere? Are workers quiescent purely because of repression or because of an improving standard of living? Is the state the willing tool of TNCs? Why did intellectuals remain out of politics for so many years?

A Comprehensive Approach

The questions I have raised are important in obtaining a deeper understanding of how Taiwan brought about spectacular growth with remarkable stability and in assessing the possibility of its serving as a model for other developing societies. It is clear that no single factor can be held up as the explanatory variable. On close examination, one sees that Taiwan’s success was a product of the interaction of a number of forces—economic, political, and social; endogenous and exogenous; constructive and destructive; fortuitous and planned; ideological and pragmatic. No book or article has attempted to link all of these together in a comprehensive way; each offers unassailable truths but only partial explanations.

A further shortcoming is that the emotional and political nature of many studies of Taiwan, and indeed the entire discourse about the place—pro–Nationalist party, anti–Na...