![]()

Part I

Life histories and narratives

![]()

Introduction

Life Histories and Narratives

Ivor Goodson

UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON

The Handbook seeks to provide a set of explanatory, exemplary and at times exhortatory texts around the theme of life histories and narratives. The Handbook comprises four parts. The first parts look at some of the general points about these approaches: their origins, the distinctive and discursive nature of life narratives and life histories, the contextual parameters and finally the multiple relationships to identity and personality.

To provide a broader gaze than is possible from a solitary editorial standpoint, I wanted to involve some of the most thoughtful and engaged scholars in developing parts which covered the manifold methodological and ethical questions that arise in these fields of study. Ari Anti-kainen and Pat Sikes are friends I have known over several decades with whom I have collaborated and co-written. Their intelligence and integrity is the key feature of their work and praxis, but they have always provided detailed methodological and ethical guidance to the field, and their parts therefore focus on these twin concerns.

Likewise with Molly Andrews, whom I first encountered in her seminal text Lifetimes of Commitment (Andrews, 1991). The idea for her part was to provide substantive focus on political lives, which illustrated and explored not only context and content but also highlighted the methodological and ethical questions which emerge in these kinds of studies.

All four parts are therefore well-integrated in their concerns and ongoing focus. Each Part Editor provides their own introduction to themselves and their parts. My intention in this introduction is to foreshadow some salient themes and provide an overview of the themes that are showcased in Chapters 1–9.

The juxtapositioning of life history and narrative celebrates the mutually constitutive nature of these research modalities and ways of knowing. Both celebrate the culmination of a representational crisis that moves our focus firmly and with conviction from the positivist pursuit of objectivity to the exploration and elaboration of subjectivity. Life histories and narratives inhabit the heartland of subjectivity and explore the multiple ways in which our subjective perceptions and representations relate to our understandings and our actions. With the huge potential in developing our studies, there are perils and pitfalls in the ‘narrative turn’ to subjectivity. This handbook seeks to explore both the promise and perils of the turn to subjectivity.

The interrelatedness of life histories and narratives is close and complementary. In the most sophisticated and complex versions of both there is close convergence from the outset – though it is important to establish the distinctive aspects of the two approaches. Narrative work focusses primarily on the story as told by the narrative teller. This often compromises the ultimate form of research studies employing this modality. The messianic vision of narrative work is to ‘sponsor the voice’ of the narrative teller, unsullied by research interpretation and colonisation. In extremis this approach foregoes any interpretation – but also any active research collaboration. The pursuit of primary authenticity can then lead to an abdication on the part of the researcher. This is a paradox that sits at the heart of some of the more messianic narrative work.

From the outset we must insist that the dangers of abdication are not a feature of all narrative work, as this volume evidences – for we have deliberately chosen elaborated notions of narrative work in this handbook. Many studies that designate themselves as ‘narrative studies’ explore the complexity of context and the multi-faced feature of human agency in ways not dissimilar from the approach of the full life history studies. Some then, fulfil the aspiration I have long promoted, following Stenhouse, of developing ‘a story of action within a theory of context’. The development of contextual understandings is vital if narratives are to be fully presented and developed.

This emphasis of contextual background is both an intellectual but also a political issue. For whilst rich in ‘authenticity’ and resonance, narratives are also eminently capable of misdirection and manipulation. Christian Salmon has written eloquently of the possible misuses of narratives, especially those that are individualised and devoid of historical context. In his wonderful book Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind, he points to enormous dangers which reside in a decontextualized or under-contextualised narrative:

The art of narrative – which, ever since it emerged, has recounted humanity’s experience by shedding light on it – has become, like story-telling, an instrument that allows the state to lie and to control public opinion. Behind the brands and the TV series, and in the shadows of victorious election campaigns from Bush to Sarkozy, as well as in those of military campaigns in Iraq and elsewhere, there are dedicated storytelling technicians. The empire has confiscated narrative. This book tells the incredible story of how it has hijacked the imaginary.

(Salmon, 2010)

One issue that needs to be addressed by those of us employing narratives is the increasing rupture between dominant narratives and contested but nevertheless apprehensible social reality. Post-modernism has of course eroded the belief in objective truth, and it is correct that all ‘truth’ may be subjectively experienced and partial. But there are truths: the sun rises in the morning and the economic crisis was caused clearly and incontrovertibly by the behaviour of the banks.

Take the latter truth, which can be empirically verified. There has been a rupture between this and the dominant narrative. Truth and narrative has ceased to co-exist. Whilst it was the banks’ behaviour that caused the crisis, the narrative that has emerged blames over-spending on the public services for the deficit caused by the banks’ behaviour. Since dominant interest groups control the narratives that are constructed; they can reposition narratives and ‘truth’ and thereby disassociate what people believe from empirical, validated reality and historical context.

These potential dangers in the misuse of narrative data are exacerbated by the uncoupling of narratives from their social location and historical context. Let’s take an example of the collection of narratives and stories presented without reference to social and historical transitions. In our study of teachers’ lives funded by the Spencer Foundation in the USA we studied teachers’ stories across the 40-year period (Goodson, 2003). In the 1960s and 1970s teachers recounted stories of professional autonomy and vocational pride. Their teaching was integral to their ‘life and work’. It expressed these deepest ideals about social organisation and social progress. For many, teaching was their life. After 2000 the more common story was ‘it’s just a job; I’ll do what I’m told’. It became a story of technicians carrying out the instructions of others and has led to a set of stories of how teachers sought fulfilment of their ideals and life missions by leaving teaching for more meaningful work.

Now, without historical context, these are just different stories of teachers’ work laid side by side with equal claims to our attention and with limited potential for understanding history and politics: life histories should seek to elucidate why during historical periods teacher narratives change and how the restructuring of schools and society impinge on the narrative storylines that are available and accessible for individual elaboration. Narratives then are best when fully ‘located’ in their time and place – stories of action within theories of context. It is when conducted in this way that life histories reach the parts that other methods fail to reach. For these reasons many scholars see life history as a more fully fledged method and a way of learning. For instance, in revisiting narrative and life history methods, Hitchcock and Hughes suggest the life history approach is ‘superior’ because of its retrospective quality which ‘enable[s] one to explore social processes over time and add historical depth to subsequent analyses’ (Hitchcock & Hughes, 1995, p. 187).

As we saw in the example above of teacher stories, this adds a quite crucial dimension to our analysis: without the contextual dimension, our narrative analysis is fatally disabled in providing social and political purchase in our accounts. Given the danger that this disabling vortex will be occupied by others wishing to ‘spin’ and misrepresent social reality, this is a fatal omission in methodology and ways of knowing. Our view in this handbook is that there is no intrinsic or inherent superiority in the use of life histories over narratives. It all depends on the contextual richness provided alongside the narrative study.

Narrative and life history research often takes a qualitative approach to data collection using in-depth interviews. The process is collaborative and requires establishing trust and close relationships. In the first instance, the researcher often encourages a ‘flow’ in the interview, with limited interrogation, to let the participants control the ordering and sequencing of their stories and reduce, but not obscure or suspend, the issue of researcher power.

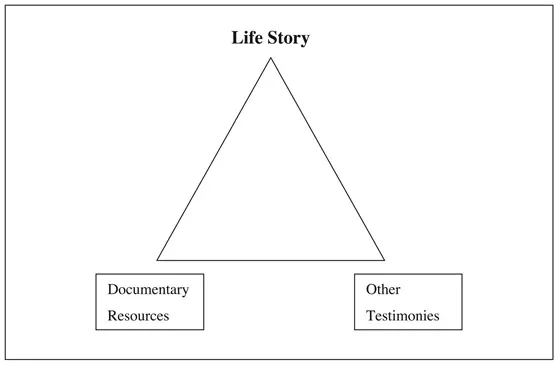

Figure P1.1 The life history

Building on the initial interview(s), further dialogues or follow-up interchange(s) can be developed. When the researcher and the participant move the ‘inter-view’ towards a ‘grounded conversation’ and away from the somewhat singular narrative of the initial life story, it can signal the move from life story to life history. This means approaching the question of why stories are told in particular ways at particular historical moments. The life history, together with other sources of data, ‘triangulates’ the life story to locate its wider meaning (see Figure P1.1). In this manner the life story is fully contextualised in time and place and is less malleable and manipulable. This is what is meant by a ‘story of action within a theory of context’.

Introducing part I

In this introductory part we focus on the implications of living in an ‘age of narratives’ and point to the particular nature of the narratives of our time – often small-scale life narratives. As we know, storytelling has always been a distinctive feature of humankind, so the recounting of narratives itself is nothing new but an immemorial practice. Rather the question becomes what sort of narratives are predominantly current and how are narratives being constructed and deployed in contemporary life. Christopher Booker has explored the theme of ‘why we tell stories’. He argues that:

At any given moment, all over the world, hundreds of millions of people will be engaged in what is one of the most familiar of all forms of human activity. In one way or another they will have their attention focussed on one of those strange sequences of mental images which we call a story.

We spend a phenomenal amount of our lives following stories: telling them; listening to them; reading them; watching them being acted out on the television screen or in films or on the stage. They are far and away one of the most important features of an everyday existence.

(Booker, 2004)

In the chapter ‘The rise of the life narrative’, I focus on how life stories are taking ‘front stage’ in our contemporary culture, but I warn that the story

provides a starting point for developing further understandings of the social construction of subjectivity; if the stories stay at the level of the personal and practical, we forego that opportunity.

So the confinement of narratives to small scale individual personal scripts constrains our capacity to develop links to the contextual background. I argue that the personal life story is an individual-ising device if divorced from context. Moreover it is a profound mistake to believe that a personal life story is entirely personally crafted for other forces also speak through the personal voice that is adopted – ‘they also speak who are not speaking’. Hence I argue we should locate our scrutiny of stories to show that the general forms, skeletons and ideologies we employ in structuring the way we tell our individual tales come from a wider culture.

Without this cultural and historical analysis, a life story study can be a decontextualizing device, or at the very least an under-contextualising device. In this chapter we develop our notions and understandings of historical time into broad historical time, generational time, cyclical time (the stages of the life cycle), and personal time. These historical contexts of time and period have to be addressed as we develop our understandings of life stories and move towards life history approaches.

The life history method has a long scholarly history that is briefly traced in Chapter 2. First conducted by anthropologists at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was pioneered by sociologists Thomas and Znaniecki in the 1920s, notably in their study, The Polish Peasant in Europe and America (Thomas & Znaniecki, 1918–1920). This work established life history as a bonafide research device, which was further consolidated by the traditions of life history work in sociology, stimulated at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s by Robert Park. Howard Becker argues that the study of The Jack Roller, Stanley (Shaw, 1930), is typical of the virtues of life history studies. He says:

by putting ourselves in Stanley’s skin, we can feel and become aware of the deep biases about such people that ordinarily permeate our thinking and shape the kinds of problems we investigate. By truly entering into Stanley’s life, we can begin to see what we take for granted (and ought not to) in designing our research – what kinds of assumptions about delinquents, slums and Poles are embedded in the way we set the questions we study.

(Becker, 1970, p. 71)

Conducted successfully, the life history then forces a confrontation with not only other people’s subjective perceptions, but our own also. This confrontation can be avoided, and so often is avoided, in many other social scientific methods: one only has to think of the common rush to the quantitative indicator or theoretical construct, to the statistical table or the ideal type. This sidesteps the messy confrontation with human subjectivity, whether it be that of the person being studied or the person doing the studying.

This confrontation sits at the heart and is the central aspiration of ...