eBook - ePub

The Policy Analyst's Handbook

Rational Problem Solving in a Political World

This is a test

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This rigorous but very accessible guide to the main concepts and techniques of policy analysis is intended for students and in-service professionals who want to become more efficient and effective in their work. The book equips readers with a structured and disciplined step-by-step approach to decision making, defining issues and applying the powerful techniques of policy analysis - always in the context of uncertainty and limited discretion. Each chapter concludes with notes and a list of supplementary sources for further reading.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Policy Analyst's Handbook by Lewis G. Irwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Scientific Method, Social Science, and Policy Analysis

1.1 Nested Challenges

Effective policy analysts are effective because they understand the various challenges inherent in the analytic task itself. In an ideal world, analysts would be able to arrive at rational answers to rational questions through a rational process of deliberation and analysis, since rationality, or the systematic consideration and selection of logical alternatives in light of carefully applied evaluative criteria, is the policy analyst’s major objective. Unfortunately, however, policy analysis almost never plays out in this way. We live in a human and political world, and with it comes a variety of subjective concerns and uncertain conditions that prevent us from ever completely reaching that ideal standard. So although we continually strive as policy analysts to achieve or at least approximate this ideal of objective rationality, human and methodological factors invariably get in the way of at least one of the steps toward that goal. From this perspective, the analytic task can be summarized as three sequential and nested processes, each containing a distinct set of methodological and contextual challenges. Effective policy analysts actively manage these challenges from the outset of their analysis.

The first of the three processes that confront the analyst is the challenge of the scientific method. When we speak of the scientific method, we are merely speaking of the goal of identifying important questions, theorizing answers to those questions, and then seeking confirmation of our theories through logical reasoning and objective observation. The basic goal of the scientific method is empirical analysis, or the establishment of facts determined by the gathering of information through one or more of the five senses. Because policy analysts, like professionals in other fields, view the world through the lenses of preconceived notions about how the world works, they find the scientific method to be particularly challenging.

Put another way, we all carry preconceived beliefs, ideological and otherwise, that tend to shape the ways in which we perceive the world. In some cases and for some analysts, maybe more often than not, preconceptions about “right” and “wrong” turn out to be the correct answers to our important questions as we make policy decisions. But when we fail to subject our assumptions about the world to the scrutiny afforded by a rigorous application of the scientific method, we run the risk of carrying faulty logic or misconceptions throughout our whole problem-solving effort. This failure results in incorrect or incomplete policy recommendations, often with dire and far-reaching consequences. In France during World War II, the failure of the Maginot Line, which led to the occupation of France by Germany, serves as an extreme example of the potentially catastrophic effect of untested and faulty assumptions. Based on outdated data, the French leadership’s assumptions regarding German intentions and capabilities caused a misallocation of resources and led to disastrous failure when intelligent and well-intentioned people assumed that things would work as they always had. For policy analysts, the application of the scientific method means always examining and reassessing your basic assumptions and basing one’s analysis on empirical evidence whenever possible.

The second process that makes the task of policy analysis challenging is the application of the scientific method to social science questions. When we speak of the social sciences, we are speaking of all fields of scholarship and policy that deal with human behavior and human interactions in society. Almost every policy question includes one or more human elements, and thus the special challenges associated with social scientific inquiry almost invariably apply to policy analyses. The basic goals of social science include empirical analysis and the establishment of facts and the validation of theories, but social scientists also often engage in normative analysis as part of their research efforts. Normative analysis is value-laden analysis that seeks to assess whether some phenomenon is “good” or “bad.” This variety of analysis comes with its own inherent challenges, a topic discussed elsewhere in this book. In general, the special challenge of the application of the scientific method to questions of social science is that human factors, behaviors, and responses are inherently complex and often difficult to measure accurately. Our efforts at wholly rational analysis are almost always bounded by the characteristics of uncertainty of measurement and the complexity of human phenomena, meaning that even in the best case we can never hope to get it right all of the time.

As if these challenges were not enough, the policy analyst faces one more set of challenges in his or her bid to achieve objective rationality. Nested within the application of the scientific method to social science is the third process of policy analysis itself. Policy analysis is a special case of social science in that this endeavor comes with its own distinctive methodological and contextual constraints. Every policy analyst operates within a context of practical and political challenges that further limit him in the pursuit of objective and rational solutions to policy problems. These challenges include a wide range of considerations such as decision makers’ boundaries, time and resource constraints, prior policy commitments, and other aspects of the policy environment and the context in which decisions will be made. We will address the particulars of these and other constraints in more detail in subsequent sections of the book. To make the task of policy analysis even more challenging, these constraints and the decision-making context frequently change at least once, even after the analyst has begun the analytic process.

Nevertheless, effective policy analysts are effective because they understand and confront these inherent and nested challenges at the outset of the analytic task. Policy analysis is hard to do well because to be successful, the analyst has to deal squarely with all three of these sequential sets of challenges, each step of which can prove fatal if ignored. When things go wrong or if the recommendation proves faulty, analytical shortcomings can usually be traced back to one of these three potential problem areas. The challenge is to anticipate and account for potential problems before beginning each successive step of the problem-solving methodology.

In sum, the policy analyst has to confront the challenges posed by the scientific method, the additional hazards of that method as it is applied to social scientific questions, and the final and critical constraints and challenges specific to policy analysis itself. In order to perform effective policy analysis, we have to understand these challenges and likely limitations of our analytic task from the beginning. Therefore, effective policy analysis must be grounded in an understanding of all three distinctive sets of challenges that face the problem solver. They are considerations that the effective policy analyst always keeps in the back of his or her mind while working through a problem. These distinctive challenges are a large part of the reason that the process of policy analysis is often iterative rather than simply sequential in its application. In the next few sections, we will examine in detail each one of the three nested processes and the related challenges that each process poses for the analyst.

1.2 The Scientific Method

As noted previously, when we speak of the scientific method we are referring to the goal of identifying important questions and then answering those questions as best we can through careful theorizing and objective observation. The effective policy analyst understands that this process is best described as a method that proceeds logically from the characterization of the problem at hand to the identification and collection of information needed to evaluate the problem. The analyst also understands that the scientific method, applied correctly, provides for the crafting of a problem-solving plan of action that will allow him to gather the data needed to analyze the problem at hand efficiently and effectively. There are always time constraints in the world of policy analysis.

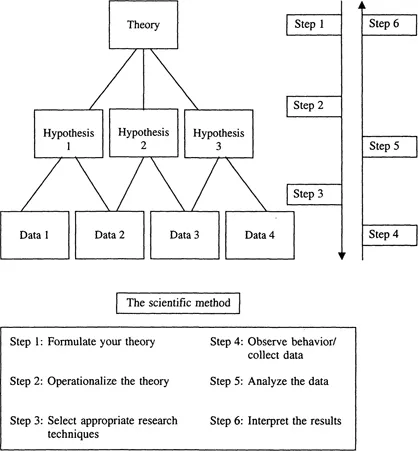

Figure 1.1 captures the scientific method in greater detail, and the research pyramid that it contains offers an easy way to visualize the scientific method as a six-step process. Each level of the pyramid represents a level of the process, and we work our way down those levels for the first three steps of the operation, then work our way back to the top of the pyramid for the last three steps. In order, the steps are as follows:

Step 1: Formulate Your Theory

In the first of the six steps of the scientific method, we formulate our theory, in essence defining the nature of our research question or policy problem. In this initial and consequential step of the process, we draw upon our own reason, experience, and judgment as well as other research in formulating a statement of our expectations. Our theory can be a relatively abstract statement about how some aspect of the world works, a hunch about a relationship between various phenomena that occur in nature or society, or even merely a statement of our area of analytical interest. It is during this step of the process that we draw upon any previous work done by others to find out what is and is not known about our particular question or hunch. In the research process viewed generally, it is during this step that we decide whether we will aim to extend or challenge the findings of the previous scholarship. The policy analyst uses this preliminary examination of the evidence to begin to structure the problem and to begin to identify the existing empirical evidence that will shape our eventual policy alternatives and the evaluative criteria that we will use to assess them.

Step 2: Operationalize the Theory

Once we have formulated our theory, the next step in the scientific method is to operationalize it. We operationalize our relatively abstract theory when we turn it into a set of concrete, measurable, and testable hypotheses. As Figure 1.1 shows, ideally we aim to create a set of hypotheses rather than only one hypothesis, as the usual problems with uncertainty make it better to have multiple tests of our theory’s validity rather than only one. During the process of operationalization, we also identify our independent and dependent variables. As these names suggest, if we believe that two variables are related in some way, we are also likely to believe that we can use one variable to predict changes in the other; the dependent variable is the one whose value depends upon the value of the other variable. We call that other variable the independent variable because we believe it to be varying freely, at least in the sense that its value is independent of the dependent variable’s value.

Figure 1.1 The Research Pyramid

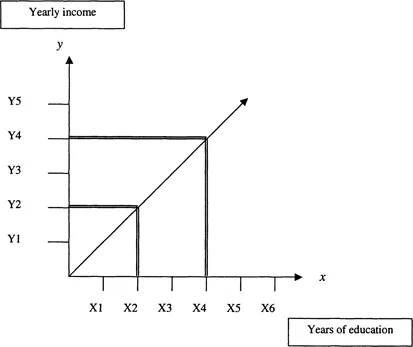

Figure 1.2 A Hypothesis in Graphic Form

When we hypothesize these types of relationships between variables, it is usually helpful to graph the relationship. Figure 1.2 shows an example of such a relationship. As we can see in Figure 1.2, this analyst has a theory that there is a relationship between a person’s level of education and his overall wealth. The analyst has operationalized that theory into a set of testable hypotheses. One of those hypotheses is described graphically in Figure 1.2, as the analyst believes that we will find a positive correlation between the variables “years of education” (the independent variable) and “yearly income” (the dependent variable). That is, this analyst expects that if we were to plot various people’s educational attainment measured in years versus their respective amounts of annual income, we would find that as the education increased, the income would increase at the same time. This means that on the graph, X4 is greater than X2, and we expect that Y4 is also greater than Y2 in a positive correlation. Conversely, in a negative correlation the value of the dependent variable decreases as the value of the independent variable increases.

It is also important to note that we may or may not believe that the changes in our independent variable actually cause the corresponding changes in the dependent variable. In some cases, we may theorize causality, or a cause and effect relationship, but in other cases we may merely see a correlation, or a statistical relationship. In spurious relationships there is a statistical relationship between two variables but that relationship is purely coincidental.

During this second step of the six-step research process, it is critical that we carefully sort out these issues while defining our key terms and translating our theory into concrete, measurable, and testable hypotheses. The policy analyst has a distinctive set of tasks to accomplish during this phase of policy analysis, tasks that are critical to the success of the analysis. These tasks are described in detail in subsequent chapters.

Step 3: Select Appropriate Research Techniques

Once we have decided on the variables we will use to test our theory, the next step of the scientific method is to determine what data we will use to measure those variables, as well as the means that we will use to gather the data. As Figure 1.1 shows, we will need to identify data to be collected for all of our hypotheses, although some of the hypotheses might rely upon the same data for measuring either the dependent or independent variables. Our basic goal here is to select types of data and collection techniques that will allow us to make generalizations about the broader theory that we are aiming to test. We want to select data and collection techniques that avoid giving us results that are sample specific, or pertain only to the particular data that we have collected.

Additionally, there are four important research design concerns that we will need to consider during this phase of the application of the scientific method. First, we want to make sure that our variables and the data that we will use to measure them are appropriate to our hypothesis. Appropriateness refers to the question of whether or not we are actually measuring the characteristic, quality, or feature that we set out to measure. For example, if we aimed to measure yearly income, but selected a technique of data collection that ignored the income a person received from interest on investments and other income outside of wages, we would be measuring wages rather than yearly income. This shift in our variable might have significant consequences for the validity of the generalizations that we would make after completing our analysis, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Note for Instructors

- 1. The Scientific Method, Social Science, and Policy Analysis

- 2. Defining the Problem

- 3. Generating Potential Courses of Action

- 4. Cost-Benefit Analysis

- 5. Multi-Attribute Analysis

- 6. Articulating the Recommendation

- 7. Implementation and Beyond

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author