This is a test

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

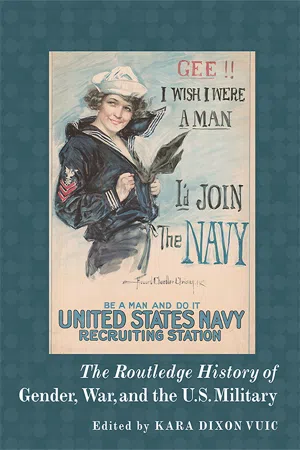

The Routledge History of Gender, War, and the U.S. Military

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Routledge History of Gender, War, and the U.S. Military is the first examination of the interdisciplinary, intersecting fields of gender studies and the history of the United States military. In twenty-one original essays, the contributors tackle themes including gendering the "other, " gender and war disability, gender and sexual violence, gender and American foreign relations, and veterans and soldiers in the public imagination, and lay out a chronological examination of gender and America's wars from the American Revolution to Iraq. This important collection is essential reading for all those interested in how the military has influenced America's views and experiences of gender.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Routledge History of Gender, War, and the U.S. Military by Kara Vuic, Kara D. Vuic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART I

Military Manpower

Gender, Service, and Citizenship in American History

This collection opens with a series of essays that trace the historical scholarship on the evolution of women’s and men’s wartime and military roles, beginning in the pre-contact era and continuing through the ongoing wars in the Middle East. The ten essays in this part each offer a close look at the ways historians and other scholars have investigated the changing nature of martial gender roles at particular moments in U.S. history. While many of the chapters focus on singular wars, others consider a broader period. All speak to the fluid boundaries between wartime and peacetime and the essential role that postwar periods play in making sense of wartime changes. Together, these chapters suggest that studies of military and wartime gender roles are central to understanding the armed forces and U.S. wars. As warfare proved a regular part of U.S. history, and as the military grew increasingly central to American life and culture, scholars have shown that gender has been inseparable from these events and transformations.

Although it is tempting to think of wartime gender roles as developing in a historical continuum, this part reveals the faults of such an approach. Each chapter chronicles how wartime needs produced gender change by demanding military and domestic labor, requiring increased martial service, and by disrupting normal patterns of life. In turn, these needs prompted Americans to broaden their understandings of particular kinds of labor as narrowly gendered. Often, however, scholars note that wartime changes were temporary, retracted at the war’s end to accommodate returning veterans’ needs for jobs and society’s broader cultural need for security and familiarity. Even as wartime gender roles retracted, however, scholars have noted the ways that wartime changes had lingering effects on postwar societies.

In this way, the chapters reveal that martial gender roles not only adapt to meet military need, but also are intimately connected to the broader patterns and changes in women’s and men’s lives, to legal precedents and developments, to cultural and social milieu and transformations. Thus, scholarship has shown that martial gender roles are inseparable from race, ethnicity, class, religion, age, and region. Moreover, as the authors note, scholars have pointed to the ways wartime gender ideologies are constructed in relationship to others, not only by contrasting men’s and women’s roles but also by contrasting American gender roles with those of enemies and peoples in occupied lands and nations.

As the chapters reveal, martial gender change also occurred and was felt on the individual level. While national needs often precipitated change, scholars have shown that women and men often pressed for change that responded to their expectations and met their demands, thereby transforming national understandings of the meanings of service. Thus, the chapters point to works that investigate gendered motivations and expectations, as well as how military and wartime service shaped individuals’ understandings of themselves as women and men, both during and after wars.

Together, the chapters demonstrate that the history of the U.S. military and American wars is a history of both great change and staunch resistance, often in the same historical moment. Through these historiographical studies of the evolution of martial gender roles, we see the rise of the citizen-soldier ideal, claims to military service as a vehicle to citizenship, and the eventual rise of an all-volunteer force. These competing understandings of service have had significant consequences for gender, for men’s and women’s political and economic status, and for the national consciousness.

1

The Shared Language of Gender in Colonial North American Warfare

Ann M. Little

COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

Gender as a category of analysis is vexing for many scholars, but perhaps especially for historians. While historians prioritize the study of change over time, almost nothing in history worldwide resists change more than ideas and assumptions about gender—how we define men’s and women’s roles in a particular society, and common assumptions about the biological fixity of gender roles that make historicizing them a challenge. This is perhaps especially true when we turn to military history, because only recently in modern global history have women been invited to serve in the armed forces, and modern militaries have struggled with their integration. Given the very modest official roles women played in early American military history, some might believe that gender is peripheral to the history of warfare. However, over the past twenty years, American historians have challenged this view with fresh research and arguments about the salience of gender in military conflict and diplomacy: First, some have demonstrated that the contested nature of masculinity is especially rich and fraught in all-male, sex-segregated institutions like monasteries, universities, and militaries, and second, others have shown that women and women’s labor were centrally involved in American military conflict.1 As we will see, assumptions about gender and the gendered nature of military prowess were commonly held by Europeans and Native Americans in the age of European global expansion, and they served as a common language that was cross-culturally understood in the history of warfare in early America.

Gender, Sexuality, and Contested Masculinities

Over the past twenty years, a number of pioneering studies about the history of men and masculinity have made it possible for historians to think specifically about the ways in which men’s gender roles and competition among men have shaped the military history of early North America. Beginning in the 1990s, historians argued that white men in early America had a specifically gendered history that varied with the life cycle and across time and space.2 In the 2000s and 2010s, scholars of warfare have added to this literature by elaborating on masculinity as it varied not just over time but across different ethnicities and cultures as well.

When we think of American history, most Americans think of history as moving from East to West as we follow the progress of English-speaking peoples from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. However, it was scholars of the Spanish empire and Indian country in the early southwest who published some of the signal studies in this field in the 1990s. Significantly, scholars of Native Americans pioneered the field. Furthermore, Spanish conquistadores landed a century before the first permanent English colonies were successfully established, and some of them made it as far west as New Mexico and California well before the plantations of Jamestowne and Plymouth were secured on the Atlantic coast.

Richard Trexler’s Sex and Conquest: Gendered Violence, Political Order, and the European Conquest of the Americas (1995) makes a provocative argument about the sexualized nature of the Iberian invasion of the Americas. He begins with the sixteenth-century Iberian fascination with the use of anal rape by Native men as a tool for subjugating and humiliating their enemies and the existence of male transvestism in some Native American communities. These men were known as berdaches, and they assumed both the social and sexual roles of women in their communities. Trexler notes that in both Native and European attitudes towards homosexuality, opprobrium was reserved for the passive victims of rape and conquest, not the powerful penetrators. Yet, he observes that “the massive recent literature on homosexual behavior has often been in denial, uncomfortable with questions of power,” and instead has portrayed berdaches as Native American forerunners of gay liberation and trans embodiment. Trexler’s view of the berdaches is that they were for the most part selected and socialized as children to transvest and perform women’s work and to offer sexual services to male warriors when Native practices of sex-segregation in preparation for war prevented sexual congress with women. His study ranges from the sexual exploitation of eunuchs and slaves in the Mediterranean world to present-day evidence of the sex trafficking of young children, demonstrating compellingly the ancient roots of the sexualized nature of military conquest as well as the transhistorical vulnerability of children to sexual abuse by adults.3

Ramon A. Gutierrez’s pioneering study When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500–1846 (1991) argues that gender and sexuality were central to the violent disruptions of both the military invasion and the operations of the Catholic missions. Indeed, the Spanish invasion was characterized by the intentional unity of military and religious authority as exemplified by the mission-presidio complex: Soldiers and priests traveled and worked together to reinforce one another’s authority, establishing military forts and missions on the same sites. Albert Hurtado’s Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California (1999), like Gutierrez’s book, demonstrates how sexuality and gender were woven into the violent colonialism of the successive Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. invasions of California. From the Spanish missions to the Gold Rush, California in Hurtado’s telling was a brutally exploitative environment for Native Americans and for Euro-American women. Virginia Marie Bouvier’s Women and the Conquest of California: 1542–1840: Codes of Silence (2001), published just a few years after Hurtado’s Intimate Frontiers, makes the sexualized conquest of California’s native people the central theme of her book, with Catholic priests and Spanish and Mexican soldiers playing interchangeably brutal roles. These three books aren’t centrally concerned with warfare; however, given the importance of the mission-presidio complex in the conquest of el Norte and the demands of Inquisition courts to enforce Catholic orthodoxy among conquered Native peoples, their discussion of mission life is an important aspect of Spanish and Mexican imperial expansion.4

A fuller consideration of the gendered nature of military and diplomatic relations between Indian people and Spaniards or Mexicans in the North American plains and southwest appeared only in the 2000s as early American women’s and gender history moved into the history of men and masculinity. In Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (2002), James F. Brooks argues that the shared honor culture of Indios and Peninsulares was built on the ownership and control of women and children. The raiding and trading of livestock and slaves became the basis for a colonial economy that linked the people of the pastoral borderlands—Apaches, Comanches, Kiowas, Navajos, Utes, and Spaniards alike—from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries. Although the slaves who were the basis of this economy were mostly women and children and the raiders and traders almost exclusively men, Brooks relegates most of his discussion of gender to the first chapter of the book. In an important article in the Journal of American History, titled significantly “From Captives to Slaves: Commodifying Indian Women in the Borderlands” (2005), Juliana Barr offers a gendered analysis of Native women slaves as well as a thorough comparison to the better-known Atlantic World-centered experience of African and creole African American chattel slavery. Unlike studies of captivity in the northeast among Algonquian and Iroquois communities, which focus on captives as adoptive family members, Barr argues that southwestern slavery was in fact more comparable to African and African American chattel slavery. Echoing Trexler’s concern that historians aren’t always attuned to the power dynamics involved in captivity, Barr notes that “in seeking to redeem the humanity of [captive women] and to recognize their important roles in trade and diplomacy, scholars have often equated agency with choice, independent will, or resistance, and de-emphasized the powerlessness, objectification, and suffering that defined the lives of many.”5

Barr takes this sensitivity to Native American cultures and power dynamics into her book, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (2007), in which she makes a strong argument for the importance of gender in mediating all cross-cultural contacts in the colonial southwest, from diplomacy and trade to mission life and military conflict. “Because gender operates as a system of identity and representation based in performance—not what people are, but what people do through distinctive postures, gestures, clothing, ornamentation, and occupations—it functioned as a communication tool for the often nonverbal nature of cross-cultural interaction.” Gender, she argues, was even more important than race because the Texas borderlands remained Indian country into the nineteenth century: “[G]ender prevailed over [race], because native controls prevailed over those of Spaniards. The Spanish documentary record makes this clear: [T]hey did ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I: Military Manpower: Gender, Service, and Citizenship in American History

- PART II: Mobilizing Gender in the Service of War

- PART III: Gender, Sexuality, and Military Engagements

- PART IV: Gendered Aftermaths

- Conclusion

- Index