- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bridges and Spans

About this book

Information about types of bridges and how they are built.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER

1

HISTORY OF THE BRIDGE

Bridges are a common sight today. We take them for granted as we make our way to school, to work, to a friend’s house, and everywhere in between. They have become an integral part of the landscapes in our world and are essential for everyday travel.

However, in the earliest civilizations, spanning a lake or mountain pass was not a simple undertaking. The bridges developed thousands of years ago were barely functional. They were not safe for large groups of people, and drownings because of a failed bridge were not uncommon.

Over time, as people gained knowledge and skill, bridges were aesthetically and scientifically designed, rather than simply being placed where convenient. Engineers eventually considered such things as anchoring, the forces of nature, and the human traffic that would utilize the structure in their designs. Modern materials and construction techniques allowed bridges to be longer, and higher, than was previously possible.

As time passed and engineering skills were honed, bridge designers started to have some fun planning the structures. This resulted in the construction of bridges that are sculptural works of art as well as completely functional.

Whether the end result is a complex suspension bridge or a simple concrete causeway, bridge design is an entirely different process today than it was 1,500 years ago.

EARLIEST BRIDGES

Before the invention of steel and concrete, the simplest way to span a short gap was simply to lay a piece of wood across it. Fallen logs were the most likely candidates for early bridges because they were sturdy and readily available. Later, probably in the fifth century B.C.E., bridges became slightly more complicated. Bark was removed from logs to allow for easier passage, and more elaborate wooden bridges consisting of multiple logs and shaped logs were possible.

One of the oldest documented wooden bridges was the Pons Sublicius, built in Rome around 621 B.C.E. Made entirely of wood, it spanned the Tiber River. In Latin, pons means bridge, and sublica referred to a wooden pick. Sublicius could then refer to wooden picks, or pilings, that were driven into the riverbed to support the bridge. Because construction of the Pons Sublicius came under the watchful eye of the papacy, it was well maintained. We have knowledge of this bridge because of contemporary writings, as well as its commemoration on a coin of Antoninus Pius, the Roman emperor from 138 to 161 C.E.

Also used in early civilizations, particularly in tropical regions, were bridges made of twisted vines or ropes. They could span longer distances than logs and were, to some extent, portable, as they could be removed and taken from place to place and were considerably easier to carry than a tree trunk! These simple structures consisted of two pieces of vine or rope: a person walking along the bottom piece held the top one for support. More complicated rope bridges used multiple ropes to construct a horizontal ladder-like bridge, usually with handrails. Such bridges are still used today on some hiking trails and remote locations to allow foot travel across rivers or valleys.

In parts of the world where large stones were prominent, flat rocks were often used to build bridges. There is evidence that stone bridges were built around 1000 b.c.e. One example is the Tarr Steps in Somerset, England.

The Tarr Steps, located in England, shows how early cultures used stones as an alternative to a traditional bridge.

ROMAN AQUEDUCTS

The ancient Romans accomplished a great many feats of engineering, including developments in bridge design. One of the most fascinating Roman contributions in this area was the aqueduct—a structure built to transport water from the surrounding countryside into the towns. This innovation relied on two important technologies: the arch and cement.

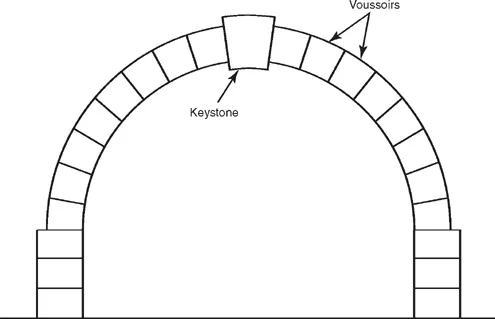

An arch is a curved segment of a structure. As used in Roman architecture, an arch consisted of a series of stones placed together to form a curve. The arch shape can span a large gap, and as arched structures use only compressive stress (see Chapter 5 for a more detailed explanation of tension and compression stresses), they are entirely self-supporting.

A Roman arch consists of different types of stones or bricks laid together to form a deliberate pattern. The sloping bricks that butt up against one another to form the arch are called voussoirs. The keystone, a specially shaped piece in the center of the arch, provides support for the bricks coming into it from either side.

The other key element to the success of Roman architecture was cement. While many types of arches were self-supporting and did not require a bonding agent (or mortar), most brick structures did need something to help hold them together. To create that bonding agent, the Romans mixed water with limestone and clay. Their formula for the mixture was so successful that modern cement is based on the same agents.

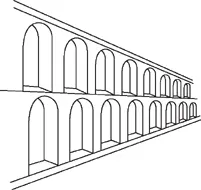

The typical Roman aqueduct (the root word, aqua, means water in Latin) was a massive structure that could have three or more levels of arches, with the largest arches on the bottom level. Smaller arches were sometimes stacked in the upper levels. Since the aqueducts were designed to transport water, a trough-like device called a sluice was added to the top level. The sluice had a U-shaped cross-section, and acted like a tiny canal that was open at the top and bounded by stone on the sides and bottom. The sluices were slanted at a very slight angle, allowing water to flow through them to its ultimate destination.

Voussoirs are wedge-shaped blocks that are held in place by the larger, more prominent keystone at the top.

Roman aqueducts, such as this one in Segovia, Spain, appeared throughout the Old World.

The earliest aqueducts were built in the fourth century B.C.E. By the first century C.E. there were close to 100 aqueducts in Rome, bringing millions of gallons of water a day into the city. Relying simply on the force of gravity, Roman engineers designed simple, yet elegant, systems to bring water into the metropolis of Rome without any mechanical parts.

While aqueducts transported water rather than people or vehicles, they spanned large gaps and served a useful community purpose. In this way, they are true ancestors of the modern arched bridge.

Aqueducts helped transport water into bustling city centers.

MIDDLE AGES AND THE RENAISSANCE

Several hundred years after the Romans, Europeans during the Middle Ages benefited from local building materials and the beginnings of industrialization. One of the major French bridges of the period is the Saint Benezet Bridge, which spans 3,018 feet (920 meters) over the Rhône River in Avignon. Because the Rhône was historically dangerous to cross, this bridge was geographically significant, as it was the only feasible crossing between the Mediterranean Sea and the French city of Lyon. Over the years, the bridge was slowly destroyed by flooding and warfare. “Sur le Pont d’Avignon” is a children’s folk song about dancing on the bridge at Avignon.

In Florence, Italy, the Ponte Vecchio, which means old bridge, was built in 1345 over the Arno River. Originally built of wood in Roman times, the bridge was formally rebuilt in the fourteenth century under the guidance of Taddeo Gaddi. The massive bridge was constructed of load-bearing masonry using three large arches. This type of bridge is called an inhabited bridge because, in addition to providing a river crossing, it houses shops and other commercial space.

The Khaju Bridge, in Iran, is an example of an early Islamic aqueduct.

Dating to 1673, Japan’s Kintaikyo Bridge is an example of a bridge that uses a combination of wood and stone construction.

The Renaissance brought with it many innovations in architecture, including advances in bridge design. The Santa Trinità Bridge of 1569, also in Florence, was built and rebuilt numerous times over the years. The final version, designed by Bartolomeo Ammannati, was commissioned by the Medici family, who ruled Florence for over 300 years. The elegant, arched stone bridge survived until it was destroyed during World War II, only to be rebuilt once again in the 1950s.

Bridge innovations were, of course, not limited to western Europe. The Khaju Bridge at Isfahan, Iran, dates to 1667 and is one of the most elegant bridges in the early history of Islamic architecture. This bridge uses pointed arches and contains covered passageways that provide shade from the hot sun. Multifunctioning bridges were common in this period, and the Khaju Bridge doubled as a dam.

Another masterpiece of seventeenth-century bridge design is found in Iwakuni, Japan. The Kintaikyo Bridge, built in 1673, has elaborate wooden arches on top of stone piers. The finely crafted wood is far more detailed than any stone bridge of the same period. Japanese craftsmanship is evident in every detail of the Kintaikyo.

IRON AND STEEL

The greatest major structural inno...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About Frameworks

- Chapter 1 History of The Bridge

- Chapter 2 Types of Bridges

- Chapter 3 The Construction Site

- Chapter 4 Calculating Design Loads

- Chapter 5 Bridge Construction

- Chapter 6 Bridge Safety

- Chapter 7 Unusual Bridges

- Chapter 8 Bridge Disasters

- Glossary

- Find Out More

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bridges and Spans by Cynthia Phillips,Shana Priwer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Makroökonomie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.