In the era of web-enabled mobile technology, one factor has changed that has enormous impact on our current understanding and definitions of the nature of teaching and learning in education. It has an effect on how schools and universities, teachers, students and decision makers approach teaching and learning. This changing factor is ubiquitous access to information through mobile devices and wearable technology (e.g., media tablets, smart glasses). It is the omnipresence of online presence, independent of where we are. More people have better access to information with easy-to-use mobile devices, anytime and anywhere; we potentially have all information always at hand via our media tablets or web-enabled phones. Such a simple-sounding development has tremendous impacts on learning. Whether we like it or not, mobile technology has already affected the way we learn: discussions and learning strategies have changed. If the learner does not know about Subject X, she merely has to search for it online, instantly. In the digital age—in an Internet-driven, networked world—constant online access supports the Homo Interneticus in searching immediately for solutions to a question or a problem. This technology-mediated social action takes place as an individual person or as the individual engages in contact with her groups and learns in collaboration.

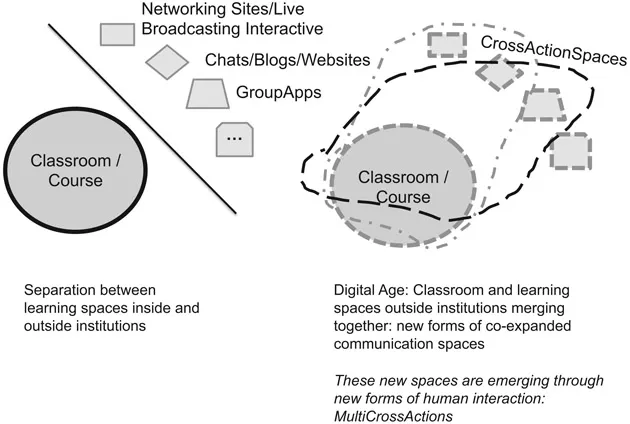

Unlike informal learning outside educational institutions, traditionally Information and Communication Technology (ICT) was segregated from the normal teaching classroom, for example, in computer labs (Henderson & Yeow, 2012). This has changed with the advent of smaller, flexible devices. Differences between laptops and small, easy-to-handle multimodal Web-enabled devices are discussed in other literature (e.g., Johnson et al., 2013). There is a shift from separating ICT and education to co-located settings (De Chiara et al., 2007) where mobile technology becomes part of the classrooms; both the offline and online worlds have merged into new forms of co-located communication spaces. These new spaces are the expansion of the traditional classroom boundaries—in short, CrossActionSpaces.

CrossActionSpaces provide various offline and online ‘rooms’ for social interaction and communication within one physical location at the same time. For example, imagine a lecture hall with 100 students in the traditional setting, where the teacher asks an open question; only one student is able to answer at any one moment. With mobile technology, all students are able to contribute and become active agents—it is the expansion of the established communication space. Traditionally, communication was limited to the physical lecture hall, and only those people that were part of the physical room could interact. With web-enabled technology, learners can consult their online networks, such as social networking sites and micromessaging services (e.g., Twitter, LinkedIn) for different reasons. Some want to find an answer to a question or solution; others want to engage in discussions about the lecture content. Such cross-actions of learners expand the given physical room to many spaces. It is the extension from those who attend in the physical location to new and other participants elsewhere. These spaces are connected to other spaces. The learner in the lecture hall and classroom interacts with her networks and these members have access to other networks, and so on.

A person is in a physical place but at the same time in two or several other online spaces; she reads information, she contributes actively in discussion boards, she shares photos about presentation slides, she searches for solutions on how to build a product such as a solar energy item at home. And other people do this, too.

Problems

Technology has not only the advantage of supporting learning and sharing information; the use of technology can shift learning to a direction where humans and learners are more and more disconnected from the social environment.

There are side effects. In a ubiquitous, digital-networked world, information, all information, seems always to be with us, in our pockets and handbags. Does this make everything perfect? No. Easy access to information does not necessarily make learning easier; access to content does not necessarily mean that a person learns. No learning progress takes place without reflection—and a smartphone, a media tablet or a laptop itself cannot make the user reflect (Jahnke et al., 2012).

Another problem emerges. The digital networked world consists of humans but also social bots, automated software programs. It is not a social media world we inhabit; humans and bots have together created an asocial media world.

Social bots, for example, copy and paste the existing content in huge amounts within a short time. In the name of its programmer, the bots influence the opinion of the human participants, for example, in politics. It is known from psychology research that the more often we hear and read the same sentences, the more readily we believe in them, even though the message might contain false information. Bots did influence, for example, the political opinions and actions of those using Twitter in the Iran election in 2009 and using online communities in the Ukraine crisis in 2014 (read further in “Twitter Bot Influences Real Americans,” NBR, 2011). “The Bot Traffic Report” from 2013 showed that 61% of all networked communication had been initiated by bots. According to Alexis C. Madrigal, senior editor of the Atlantic, he flooded Twitter with thousands of automatically generated ‘auto tweets’ and caused 100,000 visits to a single web page, in such a way that no one noticed that they were generated from the same Internet address. The networks of bots and other forms of intelligent computer machinery are part of our Internet-driven world—often with malicious purposes, such as collecting human online profiles and human patterns of activity (Boshmaf et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2012).

In addition to such invisible technical mechanisms, there are also hidden social mechanisms. When humans communicate and interact, they create new expectations, and expectations of expectations, and so forth, which create boundaries, intended or not intended, implicitly or explicitly. In the Internet world, such boundaries are, for example, online role structures (Jahnke, 2010b). To take one instance, in online courses, teachers and students have many different roles to perform. Teachers are structure givers, creators of scaffolds, experts, process mentors, designers and colearners in the workplace. Students are learners, consumers, knowledge constructors, creators, feedback givers and sometimes teachers for their peers. This role complexity is like a burden; it is difficult to juggle with the complexity of role expectations—sometimes these are contradictory and cause behavior conflicts. For example, sometimes teachers know that they are in different roles, such as that of a designer, but they do not know how to handle all the different expectations. Sometimes, students do not know that teachers expect them to act as creators; they think the consumer role is the norm. Some students expect that the teacher has the right answer and that s/he tells the student what to learn. In such cases, students will not use web-enabled technology—except where the teacher has designed for its use. This means that the teacher creates a design for learning that fosters social actions by students in such CrossActionSpaces.

These social and technical mechanisms make our environment appear to be an open world. It is not open; we only think it is open. We wish it so. Terms such as ‘open world’ have often been used in recent years, but what does ‘open’ mean? Do all people have access to all information? Is all information open? Are all people open-minded? Is everyone able to learn what and as they wish? CrossActionSpaces are communication spaces in which humans perceive a new quality, a tension between openness and role constraints.

The theories of social roles and social system theories form the basis for this thinking; they remind us that our world is made of social system boundaries in which learning is constrained by the role performance. It is not only the technical system that codes and recodes boundaries; it is human communication that enables but also restricts our way of communication and learning. Learning in this book is understood as a form of reflective communication.

Developing the approach of CrossActionSpaces further, it leads into a new model of how we think about learning, which helps to turn the given learning restrictions into learning opportunities. It also informs new types of learning technologies. In a networked world full of big data, learning is emerging from traditional role performances into multiple-role connections that can be seen in various interactions across established boundaries of systems. A person using her web-enabled devices is at several spaces, sometimes at the same time, physically and online. Cross-actions in relations are emerging. CrossActionSpaces are evolving.

This brings new questions to the agenda: how do humans learn in a digital, interactive, social and antisocial or asocial networked world, especially in such co-expanded spaces? What is the purpose of teaching and how to design for learning? What is the relationship between them?

The book discusses new forms of innovative pedagogy. More specifically, it initiates reflections about relationships of learning, teaching, pedagogy and ICT/tablets in education. What is the new normality? Challenges and unexpected factors will be illustrated. I argue that one answer can be called Digital Didactical Designs for Learning Expeditions (Jahnke, Norqvist & Olsson, 2014), which supports Inclusive Learning Spaces and education for all that does not only rely on access for all but on reflective learning for all.

1.1 Classrooms of the Future—Learning in CrossActionSpaces

In this book, I argue that the digital networked world is neither one space nor several social or sociotechnical systems; rather, it can be also understood as CrossActionSpaces. These spaces are emerging through interactions of humans using web-enabled technology. Human behavior in such spaces does not only rely on interactions but also on multiple actions across established boundaries of traditional organizations and institutions. Spaces are constituted through the cross-actions by humans.

For example, a group of people is chatting; during the discussion, open questions arise such as ‘how far away is city X’ or ‘why do so many bees die in the winter’. They use their online networks to find solutions. Another group is learning about automobile mechanics and uses the Internet to find solutions on how to fix an automobile. People are searching for information online, they are using their online networks, they make Do-It-Yourself products offline, and they are part of the maker-movement culture, on- and offline. While acting in such flexible ways, the off- and online worlds are merging into new spaces. Cross-actions by humans are the creators of these new spaces.

When human action is changing toward such cross-actions, and when learning takes place under the conditions of spaces, then the question is: how to design for learning? What is learning in such a world?

The traditional classroom has been organized around textbooks and a physical location in which to learn. Schools and universities practice teaching and learning as if there existed one right answer. However, the world in the digital age does not work in that way. First, there are always many different answers available to a specific problem. Second, when schools and universities do design learning in such a way where one right answer is available, then learners just can go into CrossActionSpaces and google for the right answers and ask their online networks. Who would not ask the Internet, when we would know the right answer is available there? When we have the Internet in our pockets and handbags everywhere at any time, why shouldn’t we use it? This means that schools and universities need new designs for teaching and learning. Instead of creating learning designs where a right answer is available, more complex problems are required where students solve problems together and become makers connecting to real-world experiences. Bring the world, and the world’s problems, into the schools and universities by using CrossActionSpaces.

The future classroom will be organized around ‘access to’ content and, moreover, access to social capital (Huysman & Wulf, 2004). Social capital is the knowledge that people have and communicate: what is not in the textbooks, nor explicitly available otherwise. Social capital can be on the Internet. It is ‘in’ the social networks; it is also in massive open online courses (Daniel, 2012); it is in Twitter and in all other forms of communication spaces, which create access to these kinds of knowledge.

Figure 1.1 illustrates how the traditional offline classroom and online clouds are merging into new CrossActionSpaces by the expansion of communication beyond the physical walls.

The future classroom will be organized especially around interaction and cross-actions. Teachers will create designs for learning that enable cross-actions conducted by students in groups, sometimes at the same location and sometimes in different places and spaces, to solve a problem in collaboration. The key design factor will be the ‘process.’ The logic of the future course design will be the process at center and not the location. Teachers design for processes first, and the locations are second. A course in schools and universities is then characterized by processes that enable student activities and cross-actions over time.

CrossActionSpaces can be described as multi-existing co-expanded communication spaces in co-located settings of online spaces and offline places that are made by cross-actions and human communication. I describe this step by step in the next sections.

Figure 1.1 Moving toward CrossActionSpaces

1.1.1 Spaces

Over the years, the classroom has been constructed as a social system (Chapter 2) in which teacher and learners meet. Designs for learning often followed an Instruction-Response-Evaluation structure (Mehan, 1979) in which students reacted to questions by teachers. In the digital age, the old classroom, however, is changing toward a more open space, especially when the teachers and students use digital media and web-enabled technology. In our tablet-classroom studies, we saw such new spaces (discussed in Chapter 6). Students use the media tablet to search for information on the other side of the classroom walls; they are makers of new products, they upload their products into a school Vimeo channel, and they even invite an audience from outside schools to join them in their learning processes. The classroom wall and the construct of the traditional social system are blurring; new spaces evolve. We can call this the system or space perspective.

1.1.2 Communication Spaces

The space metaphor does not rely on location but on communication. The space i...