![]()

1 The dynamism of the American city

Triumphs and troubles

Love them or hate them, people care about cities.

Boosters talk about “superstar cities” that are magnets for the creative class.1 They note that civilization itself is rooted both etymologically and historically in the city. Urbanity is a much desired attribute in an individual, denoting culture, education, and style. Theodore Parker, a Massachusetts divine of the mid-19th century, said that cities “have always been the fireplace of civilization, whence light and heat radiated out into the dark.”2 Kevin Lynch, in The Image of the City, observed, “Looking at cities can give a special pleasure, however commonplace the sight may be.”3 Such laudatory sentiments about cities date at least as far back as Sophocles, who wrote, “The highest achievements of man are language and wind-swift thought, and the city-dwelling habits.”4

Bosh and bunk, the detractors retort. Cities attract and concentrate all that is worst in human experience. They are the home of degeneracy, crime, and corruption, the locus of disease and discontent. “When [Americans] get piled up upon one another in large cities as in Europe,” predicted Thomas Jefferson, “they will become corrupt as in Europe.”5 Even so urbane an individual as Brooks Atkinson, the notable mid-20th century New York Times theatre critic, wrote, “All cities are superb at night because their hideous corners are devoured by darkness.”6 Those looking to find examples of dysfunction in urban America do not have to look hard: Detroit; Camden, NJ; Gary, IN; East St. Louis, IL. But, even in apparently prosperous cities, we find dangerous slums: East Brooklyn and South Jamaica in New York City; Houston’s south central Third Ward; the Ashburn, Woodlawn, and South Lawndale neighborhoods in Chicago; areas between downtown Atlanta and Hartsfield-Jackson airport.

When William Julius Wilson noted that, “in 1959 less than one-third of the poverty population in the United States lived in metropolitan central cities; by 1991 the central cities included close to half of the nation’s poor,” the statement resonated with Americans.7 By 2012, the numbers looked like this: 46.5 million Americans lived below the official poverty line: 38 million of them lived in the nation’s metropolitan areas. Whereas rural poverty gripped 8.5 million people, 19.1 million poor resided in the nation’s principal cities, and 18.1 million poor were in the suburbs surrounding those cities.8

Even so ardent a supporter of cities as Benjamin R. Barber acknowledges that we must “examine the pitfalls of the city … taking into account urban injustice, inequality, and corruption.” Barber maintains that cities exacerbate “many of modernity’s most troubling features,” and that they do so “in every domain, from education, transportation, and housing to sustainability and access to jobs.”9 As he celebrates “the triumph of the city,” Edward Glaeser worries that the city’s great strength, its density:

makes it easier to exchange ideas or goods but also easier to exchange bacteria or purloin a purse. All of the world’s older cities have suffered the great scourges of urban life: disease, crime, congestion. The fight against these ills has never been won by passively accepting the way things are or by mindlessly relying on the free market.10

It should not be considered a “spoiler alert” that this book will be arguing in favor of a particular urban configuration termed “the 24-hour city.” Nevertheless, there will be no attempt to ignore the problems of any American city. This is a story of differentiation, change, and the interrelation of urban economies and the built environment. The so-called 24-hour cities are not the “average” American city. In fact, they will be seen to be distinctively different by a number of socioeconomic and real estate-market measures. It is not a simple story, and it is one where history plays an important role.

In this chapter, we will start the story in the middle, at the mid-20th century, with a look at two of the largest American cities, New York and Los Angeles, as they were depicted in popular culture on broadcast television. We will look at the countervailing forces, powerful forces that were shaping cities in the decades prior to World War II, and the singular effects that the war itself exerted. Toward the end of the chapter, we will examine the concept of change itself, unpacking what seems to be a very simple notion and seeing that change comes in at least five varieties.

A look from our living rooms

Long before the pall of “reality television” descended over American popular culture, network TV reflected, and to some degree shaped, the way people lived their lives across the United States. Families gathered around 21-inch black and white TV sets in their living rooms, sets made in the USA by Motorola, RCA, Philco, GE, Zenith, and other “household names.” The news of the day was delivered by trusted names such as Douglas Edwards, John Cameron Swayze, Walter Cronkite, Chet Huntley, and David Brinkley. TV was one of those unanticipated but massive shifts that occurred following World War II, as technological advances emerging in military applications were translated into the private sector, and US manufacturing refocused on civilian applications.

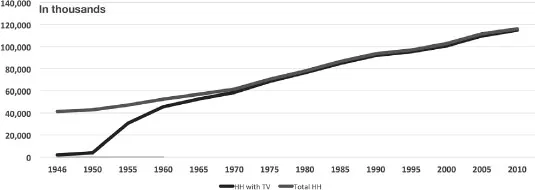

The enormous demographic wave that became known as the Baby Boom provided a vastly expanding market. Television’s penetration into that market was breathtaking. Whereas only 1 out of every 200 US households had a television set in 1946, more than 55 percent had one in 1954. By 1962, nine out of ten households owned a TV set, and since then TV ownership has become practically universal (Figure 1.1). The way Americans spent their time also changed. In 1950, the average household watched television 4 hours and 35 minutes per day. By 1975, that time had expanded to 6 hours and 7 minutes. By 2005, the time allocation was 8 hours and 11 minutes, as 24-hour programming options and technologies such as the video cassette recorder (VCR) and digital video recorder (DVR) became available and increasingly affordable.11

Television not only used more and more of the time available for all US households’ activities – reducing time available for social and civic interactions outside the home12 – but it also conveyed information about life beyond the walls of the homestead. In this, there was both good and bad.

The early decades of television are celebrated as a “golden age” that brought original dramas by Alfred Hitchcock, Rod Serling, and Paddy Chayefsky. Leonard Bernstein and Arturo Toscanini presented classical music and had a vision of bringing its cultural heritage to a mass audience.13 The Ed Sullivan Show, which at its peak in 1957 had a weekly audience of nearly 15 million viewers, is remembered for its presentation of pop stars, but also brought scenes from the Broadway stage – including West Side Story, Oklahoma!, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and Man of La Mancha – to a coast-to-coast viewership.

Public opinion was increasingly shaped by the immediacy of televised events. The 1954 Army–McCarthy hearings began the unravelling of the power and reputation of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, with the drama capped by Army attorney John Welsh’s parting response, “Senator: you’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?”14 The Kennedy–Nixon debates of 1960 brought live political discourse directly into American living rooms.

Support for the ambitious US space program was galvanized by the countdown-to-splashdown coverage of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions – with their moments of triumph and of tragedy. News of the civil rights and Vietnam War protests and counterreactions sharpened awareness of social divisions shaped by economics, politics, race, and age.

Figure 1.1 Penetration of television into US homes

Source: TV Basics, based on A.C. Neilson data (households with TV); US Census Bureau (total households)

The shocking round of assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. provided a national experience of shared grieving. The impeachment proceedings against President Richard Nixon, the ensuing Watergate hearings, and his eventual resignation from office, covered “live from Washington,” offered a lesson in civics unparalleled in US history.

For all this, however, the most remembered judgment about television in this era is that of Newton N. Minow, Chair of the Federal Communications Commission, in a speech to the National Association of Broadcasters. He challenged the network executives in 1961 to watch an entire day of their own programming, without distraction, and declared, “Keep your eyes glued to [the] set until the station signs off. I can assure you that what you will observe is a vast wasteland.”15

Minow’s characterization undoubtedly referred to the array of sitcoms, westerns, game shows, and cop shows that were the staples of network programming, especially in the evening “prime time” hours. From today’s perspective, though, there is a fair amount to be learned from that programming. Not the least interesting feature is how cities and American life were portrayed on the airwaves, both reflecting what audiences identified with and shaping how viewers perceived their contemporary environment.

Depictions of New York and Los Angeles

Let’s look at a couple of classic blue-collar sitcoms, The Honeymooners and The Life of Riley.

The Honeymooners was introduced as a comedic sketch as early as 1951 and was expanded into a 30-minute program for the 1955–1956 season. It was set in Brooklyn, one of New York City’s five boroughs, and featured two young couples living in walk-up flats. Both wives had vaguely defined careers prior to marriage, but are mostly “stay-at-home” spouses, whose characters are largely foils to their husbands. Ralph Kramden (Jackie Gleason) is a New York City bus driver, and Ed Norton is a New York City sewer worker – interestingly, both municipal employees. They both make the same wage: $62 a week. The set was spare: most action occurs in the Kramden’s main room, which served as living room, kitchen, and dining room. A chest of drawers, stove, and icebox were the furnishings. A window, without curtains, gave a view onto the fire escape and neighboring tenements. This was a no-frills, working-class slice of life – and realistic enough that, as a child of a Brooklyn bus driver myself, I imagined I could actually identify where the Kramdens and Nortons lived.16

This lifestyle was much in contrast with other popular family sitcoms, which were decidedly more upscale. The emblematic sitcoms of the era were The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952–1966), Father Knows Best (1954–1963), and Leave It to Beaver (1957–1963). Whereas Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver were set in unidentified Midwestern suburbs, Ozzie and Harriet featured the Hollywood home of the actual Nelson family, a 5,214 square-foot home set on a half-acre lot just a block from the 160-acre Runyon Canyon Park, at the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains. (The tract was in private hands, owned by the supermarket magnate Huntington Hartford, during the time the TV show ran.) The TV families were all two-parent households with several children, whose fathers were white-collar workers. Ozzie Nelson, who played himself, was an entertainer and bandleader; Jim Anderson, the dad in the Father Knows Best household, was an insurance agent. Ward Cleaver, father of “the Beaver,” was simply known as a white-collar office worker in the fictional suburb of Mayfield, whose particular job was never specified.17

But a more telling contrast to The Honeymooners is another California-situated household comedy, The Life of Riley, which was broadcast on NBC from 1953 to 1958. Chester A. Riley was the father in a suburban Los Angeles family, but, like Ralph Kramden, was a blue-collar worker. His employer was the fictional Cunningham Aircraft Company, where Riley worked as a riveter. His wife, Peg, was the long-suffering ...