Challenges of Urbanization

The beginning of this century is characterized by the dramatic rise of urban population and urban development globally.1 For the first time in history, since 2007, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities. According to the recently updated United Nations’ World Urbanization Prospects (2014), currently 54 percent of the world’s population resides in urban areas and it is predicted that such a number will increase up to 66 percent by 2050, or more than six billion people living in cities.

While Africa and Asia are currently the least urbanized regions of the world, with urban populations of 40 percent and 48 percent, respectively, it is expected that the fastest and the highest concentration of the world’s urban growth would occur in these regions, with 56 percent and 64 percent of their population becoming urban, respectively, by 2050. The majority of the current mega-cities (cities with more than ten million inhabitants)—16 out of 28—are situated in Asia (United Nations, 2014). However, the urbanization process spreads beyond the mega-cities, being even more rapid in smaller cities and towns, bringing dramatic and unprecedented changes. In fact, over the past three decades Asian cities have already experienced the most dramatic urban transformations, characterized by (but not limited to) rapid built and population densification, intensity and diversity of uses and users, increased mobility and other modes of exchange, and overall complexity of urban living conditions. Such a magnitude of urban development and transformation may be comparable to what the Western world has experienced over the past two centuries.

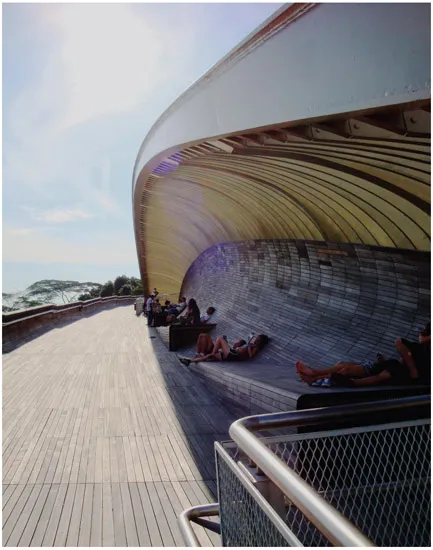

Such a rapid rise of urban development and urban population globally has inevitably led to higher demands for environmentally, economically and socially sustainable planning. As part of such demands, the provision of “high-quality public spaces” is increasingly seen as one of the key means for fostering environmental and social sustainability, and improving the quality of life in contemporary urban environments (Amin, 2006).

It is now widely accepted that quality public spaces are vital assets for a city’s livability and sustainable development, providing social, health, environmental and economic short- and long-term benefits (CABE, 2004; Carmona, 2010a, 2010b; McIndoe et al., 2005). Well designed and managed, public spaces bring communities together, shape the cultural identity of an area, provide meeting places and foster social ties that have been disappearing in many urban areas due to rapid urban transformations. Investment in public space also contributes to environmental sustainability by employing energy-efficient and less polluting design strategies, promoting greenery and biodiversity, delivering developments that are sensitive to their contexts and encouraging walking and cycling, among others. Finally, the presence of good urban design potentially attracts other investments, strengthens the local economy, and is thus a vital business and marketing tool. Such a recent shift in understanding the role of urban design in sustainable urban development goes beyond the beautification of the built environment and marks the beginning of the “new urban revolution,” as pointed out by Ali Madanipour (2006).

The main challenge of urban design today is thus to create (and re-create) good urban spaces with the ability to accommodate and respond to diverse, intense, hybrid, dynamic, contested and often unprecedented urban conditions. Consequently, the ways we understand, analyze, design, redesign and utilize urban spaces require both quantitative and qualitative re-conceptualizations. This includes challenging and reassessing the existing notions of density, space, typology and “publicness,” among others, in the context of high-density, high-intensity urban environments.

The role of quality public space in sustainable urban development becomes particularly critical in high-density contexts, and especially in those cities for which due to scarcity of land (such as Tokyo or Singapore, among others) densification may not be a matter of conscious or desirable choice, but rather an inevitable challenge. The specific governmental, spatial, economic and socio-cultural conditions of many East Asian cities have over time formed a unique platform for the high-density urban form explorations with the primary aim of optimizing the available space by maximizing capacity, while challenging the possibilities of retaining or enhancing the quality and livability in such environments. Various challenges and limitations led these cities to accept and embrace new hybrid modes of living and management, spatial and functional organization that differ considerably from the conventional urban development typologies.

Accordingly, this book aims to challenge the limits of high-density, high-intensity hybrid and dynamic development up to which the performance and vitality of urban space would remain satisfactory or even improved. Consequently, the broader aim is to explore ways of how to assure a holistic approach to environmental, social and economic sustainability, while not losing one to the other in the process of urban space development.

What is Density?

Common approaches to understanding, measuring and investigating the density of urban environments are mainly focused on built structures and capacities, with a set of objective indexes that express the concentration of built structures and/or people within a given area. This is physical or built density. Some of the most common measurements of physical density are the ratio of the building footprint to a given site, i.e. site coverage or building coverage ratio (BCR) and the ratio of building area to a given site area, such as gross plot ratio (GPR) or floor area ratio (FAR). In addition, human density refers to the concentration of people in a particular space and is typically expressed by the number of people living in the area and the number of dwelling units in the area, often in reference to age, gender, ethnicity, education and other demographic differentiators.

While such quantitative measures establish common and useful language for planners, urban designers and architects, they seem to neglect the qualitative aspects of density and intensity coming from users’ perception and multi-sensory facets of urban experience. Density indexes per se are not sufficient to fully define and understand urban density. They are relevant and meaningful only when seen in relation to a specific context. High density is often defined differently in different cultures. A specific number of dwelling units per hectare might be considered high density in one context, but low or medium in another. Finally, the same values of built and population density indexes can result in a different form and scale of the built environment. The high-rise neighborhoods in Singapore and low-rise urban blocks in Amsterdam, for instance, may have similar FAR values, while being very different in their spatial configuration.

In fact, “soft” information that originates from users’ subjective spatial experience and perception of an urban setting is often more evident and more powerful than the underlying density numbers. The human perception of density differs from the scientific one, expressed through space and population density indexes. It refers to a set of bodily and mental mechanisms and processes, which serve to organize, identify and interpret all sensory information available in space. It is thus crucial for understanding, responding to and interacting with the built environment. Accordingly, in addition to the “objective” measures of urban density, the perceived density is expressed in more subjective terms. It refers to an evaluation of spatial conditions, including estimations of the amount of people within a space, space availability and spatial arrangement (Cheng, 2010; Rapoport, 1975), a process molded by users’ cognitive abilities, socio-cultural backgrounds, learned experiences and memories (Alexander, 1993; Malnar & Vodvarka, 2004).

Perceived density is related to but also confused with crowding, being described as the negative assessment of density that causes psychological stress in space users (Churchman, 1999). Certain spatial conditions, such as limited space, channeled movement or level of enclosure, could intensify the experience of crowding (Mackintosh et al., 1975; Saegert, 1979). Even though it may be a prerequisite for causing a sense of crowdedness, density by itself is not sufficient to create a crowding experience (Stokols, 1972).

In order to fully understand and enhance the performance and livability of urban spaces in high-density conditions, a more holistic and intuitive approach that would incorporate both “hard” (physical environment) and “soft” (user’s perception) information on density and intensity of urban spaces is needed.

Is the Denser the Better?

Increase in density of urban form and urban population is a worldwide trend and it is thus unsurprising that it has received a considerable amount of attention in contemporary research and academic discussions, especially in reference to its high impact on environmentally and socially sustainable urban development. Yet, in light of the ongoing debate, there is no clear consensus as to whether high density is a good or a bad condition for the city and its dwellers.

The majority of continuously growing recent literature advocates for high-density, high-intensity, compact, mixed-use and pedestrian-oriented urban development as the desired strategies for sustainable urban growth, as opposed to unsustainable sprawl development (see, e.g., Chan & Lee, 2007, 2009; Ewing et al., 2008; Jenks et al., 1996; Newman & Kenworthy, 2006; Sabaté Bel, 2011). In line with such an understanding, it is often argued that the cities of today should be compact and densely populated with people, activities and movement, while maintaining the right balance to ensure non-...