Introduction

For the protagonists of two well-known Biblical stories, to touch is to believe. So Thomas, in the King James Version, says: “Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe” (John 20: 25). The narrative, with an ascending tricolon, suggests that the finding of the eye must be backed up by a poking finger and further by the application of the whole hand for Thomas to believe that Jesus has come back from the dead. The second, older story tells how Jacob, disguised as Esau to deceive blind Isaac, succeeded in his trick because Isaac trusted his tactile and olfactory memory more than his ears:

‘I pray thee, that I may feel thee, my son, whether thou be my very son Esau or not’. And Jacob went near unto Isaac his father; and he felt him, and said, ‘The voice is Jacob’s voice, but the hands are the hands of Esau’.

(Genesis 27: 21–2)

Isaac without hesitation disregards the perceived identity of the boy’s voice in favour of the feel of his skin (as hairy as Esau’s, because covered with animal hide) and, soon thereafter (27: 27), the smell of the clothes he wears (Esau’s).1

There are no comparable episodes in Greek epic or tragedy. Blind heroes do not rely either on their nostrils or on their hands to try to identify individuals they cannot see. Touch helps the blind find his way or measure distance, as with the seer Phineus, who “feels (ἀμφαφόων) for the walls” to reach the door of his dwelling and welcome the Argonauts (Apollonius, Argonautica 2.198–9); or with Polyphemus, who “gropes about (ψηλαφόων) with his hands” to find the stone that blocks the entrance to his cavern (Odyssey 9.416) and “feels” (ἐπεμαίετο) his sheep and his ram, searching for Odysseus and his comrades (9.441, 9.446); or again with the blind judge who could “feel” (ἀμφαφόων) with his hands how much farther Odysseus’ discus has reached than the others’ (Odyssey 8.195–7). Touch also makes physically present to the blind his loved ones and their love. Oedipus greets Ismene’s arrival at Colonus with these words: “Child, you have come? … Child, you have appeared? … Touch me (πρόσψαυσον), child”. And she: “I am touching (θιγγάνω) both of you” (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 327–9).2 For Oedipus, Ismene fully “appears” when he feels her hand. But the blind man knows who she is, for he has followed her arrival with his ears, by listening to Antigone’s agitated description of her approaching (310–23).

Tragic characters who are sighted come to recognize the identity of other characters primarily through their eyes, by inspecting a bodily feature or an object that functions as a token. Hearing, too, can play into the recognition process, when the token is cross-examined or when the truth is revealed from stitching together bits of narratives (as in Oedipus the King). In contrast, touch participates in recognition scenes only once the identification has occurred, as the main sensorial channel to express the happiness generated by the unexpected discovery. Tactile effusions are a regular staple of dramatic recognitions:3 but the hands are not their means.4

In the Odyssey as well, the protagonists of recognitions abandon themselves to the joy of touching each other after the happy reunion. Recognition always draws two bodies together, through kisses, embraces, the clasping of hands.5 The Odyssey, though, exploits touch also to bring about recognition, in the episode in which Euryclea identifies her master by feeling his scar while she washes his legs. In that episode touch rules, the loving touch of the old nurse whose hands discover the truth and, in response to their discovery, the aggressive touch of the hero stripped of his disguise.

This essay is concerned with the role of touch in the footbath scene: how does touch work in the process of recognition, compared to sight and hearing? And why does Odysseus’ old nurse, and no other, come to the truth with her hands rather than with her eyes, ears or thought? What do the sensorial means by which she discovers Odysseus tell us about the nature of their relationship?6 To conclude, I briefly discuss two Roman adaptations of the scene, Petronius’ witty rewriting of it and its stage rendering by the tragedian Pacuvius, and suggest possible reasons touch acquires even more prominence there than it has in Homer.

Euryclea’s hand

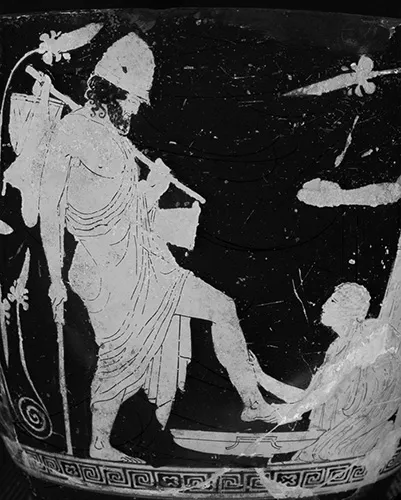

A mid-fifth-century vase (Figure 1.1) brings the paramount role of touch in the footbath scene upfront by depicting Odysseus with his leg in the centre of the visual field and Euryclea as she feels his skin from a kneeling position. In the words of one critic, “her right hand moves up his silhouetted lower leg as if searching for the scar. Indeed, perhaps she has just felt it, for she raises her head toward her master”.7

The sensitivity to the work of touch that we glean from this painting is generally not shared by discussions on the Homeric scene, which tend to focus on other aspects of it and to pass over or underestimate its tactile texture; and this since antiquity.8 Aristotle mentions the scene approvingly for the manner in which the token of identity, the scar, is exploited: instead of being exhibited by Odysseus with the intended goal of producing recognition, as it happens later with Eumaeus and Philoetius, the scar is discovered by chance, and the discovery produces a sudden and dramatic reversal (Poetics 16.1454b25–30). But Aristotle does not comment on the sensory medium involved. His silence is consistent with his general interest in the objects and circumstances that trigger recognitions or in the artistry of their unfolding, rather than in the role of the senses in them. The philosopher’s own taste favours recognitions that are the least dependent on immediate sense perception: the best ones, he says, are those “arising from the facts themselves” (Poetics 16.1455a16–17), as in Oedipus the King, where the truth comes to light by a chain of revelations. The second best is “through deduction” (ἐκ συλλογισμοῦ), as in Aeschylus’ Libation Bearers (in Aristotle’s, biased, reading): “someone similar to me [Electra] has come; only Orestes is similar to me; therefore Orestes has come”.9 This kind of recognition results from purely logical inferences. The only category for which Aristotle acknowledges the sensory medium is “recognition by memory” (διὰ μνήμης), and the only senses he acknowledges are hearing and sight: the sight of an object, the hearing of a story, which causes the concerned character to remember events of his life and betray his emotion, thus prompting the recognition (Poetics 16.1454b37–55a6).10

Contrary to Aristotle, the Byzantine scholar Eustathius notices the active role of touch in the footbath scene but wavers between attributing the recognition to touch or to sight and hearing. For him, touch is the verifier of a discovery that Euryclea has already made. As she readies herself to wash the feet of Penelope’s guest, she tells him: “I have not yet seen any man as similar to another as you are to Odysseus in appearance, voice and feet” (Odyssey 19.380–1). Eustathius takes these words to mean that Euryclea has recognized Odysseus by those features:

It seems that Penelope looked at Odysseus modestly, not in the fashion of her cousin Helen, whereas the nurse cast a busier eye on the whole stranger (περιεργότερον δὲ ἡ μαῖα ἐπιβάλλειν τὴν ὄψιν ὅλῳ τῷ ξένῳ), and the similarities [to Odysseus] were settled more exactly … Hence, note, Odysseus’ disguise by Athena was nothing but an artful concealment, directed … at the simple minded and those unable to scrape up his recognizable features. For the dog Argus was right on the mark in its perception (ἀκριβὴς ὢν αἰσθέσθαι) and now the old nurse knew (ἔγνων) Odysseus.

(Commentary on the Odyssey 2.206.42–207.1)

Eustathius equates Euryclea’s inquisitive eye with Helen’s in the episode (narrated by her in Odyssey 4) in which she unmasks Odysseus’ identity when he spies on Troy dressed like a pauper, as he is in the foot-washing scene. Both women, the critic argues, see through the disguise.

Eustathius continues: Odysseus attempts to deny that he is Odysseus by agreeing to the resemblance (“old woman, so they all say who saw both of us with their eyes, that we are much alike”: Odyssey 19.383–5), but “does not persuade the nurse”, who “lurking in the recesses of the room will grope for the sign, the scar (τὸν γνωρισμὸν ψηλαφήσει τὴν οὐλὴν), as she washes Odysseus, and will know the truth”.11 Euryclea would not discover the scar by serendipity but would search for it to confirm her prior discovery of the stranger’s identity. Hers would be a “curious hand”, pursuing the curious investigation of the eye.12 On this interpretation, touch only serves to complete the work of sight and hearing, to provide the final and decisive evidence of a truth of which Euryclea is already certain. For the Byzantine scholar her hands seek the known sign, gnōrismon, rather than just coming to feel the scar in its startling concreteness.13

Euryclea proves Eustathius wrong. She says straight out that her hands, not her eyes or her ears, pierced through Odysseus’ disguise: “And I did not know you until I handled all the body of my master” (οὐδέ σ’ ἐγώ γε / πρὶν ἔγνων, πρὶν πάντα ἄνακτ’ ἐμὸν ἀμφαφάασθαι, Odyssey 19.474–5). Only touch provides Euryclea with certain knowledge: egnōn. Eustathius transfers egnōn from her feeling hands to her earlier impression of a resemblance, whereby he devolves to sight and hearing the cognitive work that Homer assigns to touch.14

Homer brings touch to the front-stage by darkening the scene. As he is about to have his feet washed in an “all shiny (παμφανόωντα) cauldron”, Odysseus shies away from the light:

ἷζεν ἀπ’ ἐσχαρόφιν, ποτὶ δὲ σκότον ἐτράπετ’ αἶψα·

αὐτίκα γὰρ κατὰ θυμὸν ὀΐσατο, μή ἑ λαβοῦσα

οὐλὴν ἀμφράσσαιτο καὶ ἀμφαδὰ ἔργα γένοιτο.

νίζε δ’ ἄρ’ ἆσσον ἰοῦσα ἄναχθ’ ἑόν· αὐτίκα δ’ ἔγνω

οὐλήν

He was sitting by the hearth, but instantly he turned towards the darkness, for suddenly a thought occurred to him and he feared that, taking hold of him, she might notice the scar and the facts be revealed. But she drew near and washed her master. And suddenly she knew the scar.

(Odyssey 19.389–93)

Is Odysseus’ abrupt receding from the light aimed only to prevent Penelope from discovering his identity? Or is he hoping to avoid detection altogether? The indetermination of the language authorizes this additional reading: “he feared that … she [Euryclea] might notice the scar”. Implying: “maybe she will not, if she cannot see it”.15 Whatever the case, the darkening creates an intimate space where touch, unaided by vision, will operate more intently and sharpens the audience’s awareness of Euryclea’s hand, which straightaway notices without her seeing: “she drew near and washe...