![]()

1

Introduction

Donald R. Hickey and Connie D. Clark

The output of books on the War of 1812 over the past 25 years has been little short of astounding. A surge that began about 1990 gained even more momentum around 2009 in anticipation of the Bicentennial commemoration. Now that the commemoration is over, we are likely to see a fall-off in production. Still, we are left with a much fuller and richer understanding of the “forgotten conflict” because so many scholars—American, Canadian, and British—academic and independent alike— have made it their business to examine or reexamine either the war as a whole or some aspect of it.

Not all dimensions of the conflict have received equal attention. Scholars have shown little interest in revisiting the causes of the war. Although Alan Taylor has recently suggested that a contest between rival visions for North America—loyalist versus republican—played a significant role in generating the conflict, most scholars have accepted the interpretation embraced by contemporaries that was endorsed by Henry Adams in 1890 and then confirmed again in the mid-twentieth century by the scholarship of A. L. Burt, Reginald Horsman, and Bradford Perkins.1 According to this view, the war was fought over neutral rights. More specifically, the United States went to war mainly to force the British to give up the Orders-in-Council (a series of executive orders that restricted American trade with Europe) and impressment (the Royal Navy’s practice of conscripting seamen from American merchant vessels). In the language of American contemporaries, the war was waged for “free trade and sailors’ rights.” True enough, the United States invaded Canada, but this was simply the means to an end. With only 17 warships (compared to 515 for the British), the young republic could hardly challenge Great Britain on the high seas. This left Americans with little choice but to try to bring pressure to bear on the mighty Mistress of the Seas by targeting her sparsely settled and most accessible North American provinces, namely Upper and Lower Canada.

The war’s military history, by contrast, has generated considerable interest over the past 50 years. No doubt this is partly because of the inherent excitement of revisiting battles and campaigns. It is probably also due to the remarkable geographical extent of the war. The fighting stretched from Mackinac to Mobile in the west, from Detroit to Montreal in the north, from Eastport (in Maine) to Cumberland Island (in Georgia) along the Atlantic Coast, and from Pensacola (in Spanish Florida) to New Orleans on the Gulf Coast. In all, there were nine major theaters of operations on land and a tenth on the high seas that included not only the Atlantic Ocean but the Pacific and Indian Oceans as well. Nor was this simply an Anglo-American conflict. The War of 1812 also included two Indian wars, one in the Old Northwest and another in the Old Southwest, and there was even a desultory and yet destructive war, known as the Patriot War, waged against Spain in East Florida. Given the extraordinary range of campaigning that took place in just 32 months of warfare, it is hardly surprising that so many scholars have been drawn to the war’s military history.

Given the remarkable scholarly output, it seems fitting that we assess what we now know about the war. That is the purpose of this handbook. We have lined up leading students of the conflict and asked each to write an original essay that brings us up to date on the state of our knowledge and also identifies the leading works that have informed our understanding. Our contributors are almost all senior scholars, with an average age of around 60 and some 40 years of experience as historians.

We start with an essay on the big picture contributed by the prolific British historian, Jeremy Black of the University of Exeter. Black explains the international context of the war, showing in particular how events in Europe not only led to the War of 1812 but also shaped its course and conclusion. Next, a scholar with broad interests, Canadian John Grodzinski of the Royal Military College, examines British strategy for waging the war. He is followed by Britain’s most accomplished naval historian, Andrew Lambert of King’s College London, who traces the extraordinary impact that British naval power had on the course of the war. We then hear from another Canadian historian, retired civil servant and independent scholar Faye Kert, who explores the mechanics and impact of privateering in the war. After that our first American historian, David Curtis Skaggs, who enjoys emeritus status at Bowling Green State University, weighs in with an essay on the central role that the war on the northern lakes played in shaping the course of the conflict.

Next in our lineup are two historians who examine important theaters of operation. Christopher George, a transplanted Englishman who has long lived in America, examines the British campaigns in the Chesapeake (including the occupation of Washington and the defense of Baltimore), and American Gene Smith of Texas Christian University follows up with an analysis of British operations on the Gulf Coast that culminated in Andrew Jackson’s victory at New Orleans. Yet another American, independent scholar and editor Douglas DeCroix, follows with an essay on the weapons and tactics employed in the war, and we then hear from Canadian Carl Benn of Ryerson University, who presents a comprehensive treatment of the role of indigenous people.

Next up is the work of several scholars who explore the domestic history of the war. John Stagg, a native of New Zealand who has long been at the University of Virginia, looks at the war’s domestic history in the United States. Canadian James Tyler Robertson, who teaches at Tyndale Seminary, examines the domestic history of Canada. American Walter Arnstein, Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois, offers a portrait of Great Britain during the war. American Alan Taylor, who holds the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Chair at the University of Virginia and has the rare distinction of having won the Pulitzer Prize in history twice, offers up a compelling treatment of the role of American blacks in the war. Another American, Nicole Eustace of New York University, closes out our domestic history by giving us an essay on U.S. culture during the war.

We next hear from Robert McColley, another Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois, who offers a fresh look at the diplomatic history of the war. American Don Hickey of Wayne State College in Nebraska discusses the war’s unappreciated but lasting legacy. And Canadian Ron Dale, who recently completed a career with Parks Canada, shows how the war has been commemorated over the years. Don Hickey then weighs in again, this time tracing the historiography of the war, and fellow American, independent scholar Ralph Eshelman, closes out our handbook with a detailed chronology of the war.

We believe that these essays, written by a veritable who’s who in the 1812 community or in allied communities, offer a wealth of information likely to satisfy any palate. We invite readers to sample the essays or to feast on the entire collection. We don’t think anyone will be disappointed. We are confi-dent that this handbook will prove to be a valuable resource that will be recognized as an important benchmark in the historiography of the war.

***

In preparing this volume we have incurred numerous debts. We would like to thank Kim Guinta and the rest of the staff at Routledge for giving us the freedom to develop this handbook as we thought would best serve the needs of the project. We also want to thank all the scholars who took time from their busy schedules to contribute an essay. We were pleasantly surprised that almost everyone we asked agreed to contribute. We are indebted to Charissa Loftis at the U.S. Conn Library at Wayne State College for ferreting out information that we requested, and to Terri Headley at the Interlibrary Loan Desk who showed her usual facility to find and borrow just about any book or article that we wanted to look at. Finally, we want to thank our copy editor, Kathryn Roberts Morrow.

Note

![]()

2

The International Context of the War of 1812

Jeremy Black

On November 8, 1814, the Prince Regent opened the parliamentary session with a speech that left no doubt about the context of the War of 1812. “[T]his war originated in the most unprovoked aggression on the part of the government of the US, and was calculated to promote the designs of the common enemy of Europe [Napoleon], against the rights and independence of all other nations.” Was he correct? All wars sit within multiple contexts, with the international context always being one of the most signifi-cant. This is particularly the case for the War of 1812 because Britain, one of the two major combatants, was also involved for most of its course in a more major struggle, and one that it saw as more important. This was the arduous war with Napoleon’s France, one that, with one short gap in 1802–03, had been going since 1793. To a degree, the War of 1812 was a part of the Napoleonic Wars, just as other small conflicts have been subsumed within umbrella wars, notably the two World Wars and the Cold War. That was certainly the perception of the people and government in Great Britain. To them, the War of 1812 was nothing more than an inconvenient sideshow of the Napoleonic Wars.

To present the War of 1812 as a part of the Napoleonic Wars risks not only moving the focus of Anglo-American conflict away from North America, as is indeed appropriate, but also diminishing the U.S. role in the war as well as the place of the war in American public history. That would be a misleading response to the vigor with which many American politicians argued the case for war with Britain, a vigor that bore fruit in a declaration of war on Britain that the British government did not want. However, the argument of these politicians in part related to this wider context. Moreover, there were instructive parallels between Napoleonic attitudes and those of the Democratic-Republicans. Whereas the French revolutionaries had seen their revolution as ideological and for export throughout the Western world and beyond, this was not the attitude of their American counterparts, nor of Napoleon. Nevertheless, in each case, their wish to defeat Britain also drew on ideological currents.

America and France

The sense of American distance across the Atlantic helped ease America’s relations with Western powers, notably France, but this distance also fostered a degree of unreality in responding to the real or supposed policies of these powers. This unreality was taken further by Jefferson’s animus against Britain, an animus he denied.1 As a result, he and his followers judged British actions toward America without considering the pressures created for Britain by its conflict with France. Far from focusing on America, Britain was primarily concerned with preventing the neutral Americans from trading with France and thus circumventing the British blockade. This blockade was designed to weaken the French economy, a mirror to the French attempt to block and harass trade with Britain.

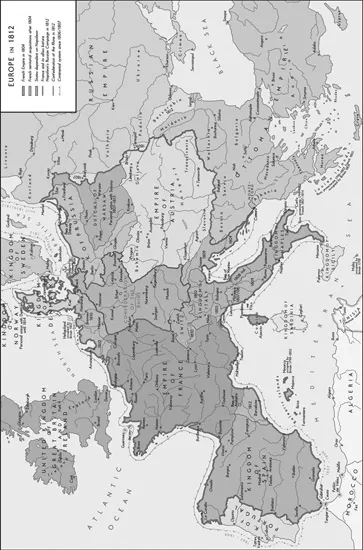

Figure 2.1 Europe in 1812.

As with Britain against Germany in 1940–41, this blockade was seen by Britain as the key way to strike at the power that dominated the European continent. However, to the American government in the 1800s (unlike in 1914–17 or 1939–41), this control over trade, including grain supplies, was unacceptable, as was the impressment of sailors of British origin. The 1809 Non-Intercourse Act, which banned trade with Britain and France, was replaced in May 1810 by an Act, sponsored by Nathaniel Macon, which established restrictions on Britain or France if the other agreed to respect America’s rights. This legislation, however, was cleverly manipulated by Napoleon in order to turn America against Britain. Another nonimportation Act, passed in February 1811, prohibited British goods and ships, while permitting continued exports. The British government correctly argued that the French repeal of measures against American trade was fraudulent, and that Britain was being treated unfairly. Far from altering the terms of the Atlantic economy, America was becoming a player, if not a tool, in the struggle between Britain and France.

That was also an aspect of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, a measure aptly seen by Napoleon as likely to shift America further to his side. As a result of the purchase, America now had a far longer frontier with Canada, which increased the potential American challenge to the British position there as well as American concern about British links to native Americans. Moreover, Jefferson and others overestimated American power after the Louisiana Purchase, which can therefore be seen as partly responsible for the deterioration in relations with Britain. Jefferson understood the potential of the American West and was correct in his long-term appraisal that America would become a world power. But he mistook America’s marginal leverage, in the threatening bipolar dynamic between Britain and France 2, for a situation in which all three were major powers. The last was not in fact to be the case until the 1860s settled the North American question, the issue of dominance in North America.3

Madison, who had been Jefferson’s Secretary of State and longtime friend and ally, followed his reasoning reflexively when he became President in 1809. This attitude ensured that American policy-makers saw little reason to compromise with Britain over the regulation of trade. Manipulated by Napoleon, Madison foolishly thought he had won concessions from France that justified his focusing American anger and the defense of national honor on Britain, whereas, in practice, French seizures of American shipping continued. This degree of manipulation does not form part of American public history about the background to the war.

In 1812, Madison appeared to have the choice of backing down in his dispute with Britain in order to assuage domestic pressures or of forcing Britain to back down, in part by extending commercial warfare in the shape of a conquest of Canada. Such a conquest would have a variety of consequences, including depriving the British of a key source of the naval supplies necessary for maritime activity. Madison underestimated the risks of trying to force Britain to yield, but this failure was greatly accentuated because the American government did not anticipate Napoleon’s journey, in 1812–14, from imperial conqueror to exile. John Threlkeld of Georgetown was to attribute the “wicked war” first “to the leaning of our government to that of France.” 4 The American press carried extensive news of France’s naval buildup, which underlined Britain’s vulnerability.5 In an ahistorical but prescient moment, Richard Glover, a Canadian historian writing in 1964, compared the United States in 1812 to Mussolini’s Italy which in 1940 joined Hitler’s Germany against Britain when the latter was as weak and vulnerable as it had been in the face of Napoleonic power in 1812. He might as well have referred to the Japanese attack on the British and Dutch empires in the Far East in December 1941.

The American misjudgment of Napoleon included an assumption that war between France and Britain would be bound to continue and would thus place Britain under pressure in any conflict with the United States. In fact, on April 17, 1812, Napoleon offered Britain peace, essentially on the basis of the status quo. Suspecting an attempt to divide Britain from her allies, the British ministries on April 23 sought clarification on the future of Spain, as they were unwilling to accept its continued rule by Napoleon’s brother, Joseph. Napoleon did not reply, and that ended the approach. Neither side probably was sincere in suggesting talks, but the possibility, however distant, of a negotiated

Figure 2.2 Napoleon Bonaparte was the preeminent military figure in Europe. He rose to power in France in the late 1790s and dominated Europe until forced to abdicate a second time after his final defeat at Waterloo in 1815.

end to the war in Europe was one that would have put a bellicose United States in a very difficult position and should have concerned its policymakers. Irrespective of French moves, Madison had departed from Jefferson’s principles in foreign policy. Crucial to these was an attempt to maintain neutrality in great-power confrontation, which Jefferson pres...