![]()

Collision (Ship to Ship) at Sea

Introduction

With any collision at sea the number of variables will not only influence the outcome but generally means no two collisions are ever the same. Each collision will be unique because of the position of contact, the weather prevailing at the time, the geography, a loaded or light condition, Masters’ experience, day- or night-time scenario, etc. So many factors will differ that no one, least of all this author, could hope to provide an answer to every situation. The very best that can be produced is to develop a general format that would be acceptable for the typical, average incident.

Clearly, the avoidance of collision in the first place is the obvious way to go, on the premise it is better to prevent than to cure the after effects. However, we do not live in a perfect world and accidents do occur. The point of impact in a collision and the subsequent damage will differ accordingly. Subsequently, the immediate and long-term corrective actions will differ in accord with each scenario. A noticeable example can be readily seen where two similar collisions take place. One vessel is struck below the water line and would probably require pumps to be activated on the affected area, whereas another vessel is struck above the water line and doesn’t lose water-tight integrity and has no need to put pumps into operation.

The law of providence could have major ramifications for casualties so involved in collision incidents. What cannot be left to chance are the legal aspects surrounding a collision, or the medical treatment required by any casualties so involved. Masters and senior officers receive little or no experience in dealing with a real-time casualty incident until they find themselves in the thick of it. Potential background training can have a limited effect, but a strong belief in the first principle of the Safety of Life at Sea is by far a greater motivator to do what is right and necessary.

Collision: Immediate Effects

Reactions following any collision at sea are bound to generate a certain level of shock among personnel on board any vessel so involved. This sudden shock experience can expect to last an indefinite period of time. The ramifications of not acting positively as soon as practical after this initial period of shock are not worth contemplating. In other words: get over it and let the training kick in.

Certain ranks within the shipping industry have usually had a degree of emergency training and hopefully will react positively and practically. Actions being based on the first principle of ‘The Safety of Life at Sea’ are paramount. If the position of the Master is considered, he has a legal obligation to stand by to render assistance to the other vessel. This is all very well, but could a man or woman think only of a third party’s needs, in isolation to his own ship and own crew’s safety?

Any actions by the Master or Officer in Charge of either vessel can only be made from a position of strength. Therefore, unless he or she wants to escalate the situation, certain basic needs have to be fulfilled quickly. An immediate requirement for the person in charge is to take the ‘conn’ of the vessel and establish a command chain. Sounding the general alarm as soon as possible if it has not already been initiated could be seen as the most immediate of activities. However, it should be realised that no single individual can expect to do everything himself; he must delegate activities to realise best effect.

A history of drills during routine voyages can prepare officers and crew members for that unexpected emergency incident. If personnel know their stations, then the chain of command can expect to permeate through any catastrophe. Activities need to be prioritised; there is no point in sending a distress message before obtaining a position or gaining knowledge of the immediate problem(s).

NB. This assumes Masters and ship’s officers are alive and capable of conducting emergency operations.

A series of activities should take place, probably starting with ship’s officers reporting directly to the bridge following impact damage. The Master would expect to order his Chief Officer to carry out an initial ‘damage assessment’, while the Second Officer (Navigator) would probably take over as the Officer of the Watch and obtain the ship’s position. (Different companies/ships employ different ranks in differing roles.)

Personnel could be expected to take up the duties of helmsman and lookouts, while a third mate could be designated as communications officer. Each incident would expect to generate exceptional activities, over and above normal routine. Certain activities on certain ships can be coordinated quickly, like the closing of watertight and fire doors. Or, for example, placing engines on ‘stand-by’ for immediate readiness where the ship is not fitted with bridge control capability.

Correct interpretation of data will allow critical activity to reduce casualties and loss of life. Incoming information should fit into an acceptable framework which takes into account all eventualities.

An example collision framework could include any or all of the following immediate actions:

For the role of Master (after collision impact at sea)

1 Move immediately to the navigation bridge and take the conn.

2 Stop the ship’s own engines if underway and making way, depending on the position of the collision and how the vessels have struck. A few revolutions on engines could reduce the permeability by keeping the bow plugged into the damaged area.

3 Sound the general emergency alarm if not already activated.

4 Order a roll call and check the ship’s complement for casualties.

5 Close all watertight doors.

6 Close all fire doors.

7 Order the engineers to stand by and go to an alert status in the machinery space.

8 Obtain the ship’s position in latitude and longitude by any reliable means.

9 Turn the ship’s ‘deck lights’ on and display the vessel’s ‘not under command’ (NUC) lights.

10 Designate an immediate Communications Officer.

11 Order the Chief Officer to obtain an interim ‘damage assessment’.

12 Order the muster of ‘damage control parties’.

13 Activate deck parties to turn out lifeboats and a rescue boat.

14 Bring a bridge team together to include lookouts and helmsman.

15 Order a local weather forecast to be obtained as soon as practical.

NB. Under GMDSS, a dedicated Communications Officer is appointed. Where officers are limited in numbers this may not be a practical option to isolate an officer to this duty alone – handling communications to the detriment of all else.

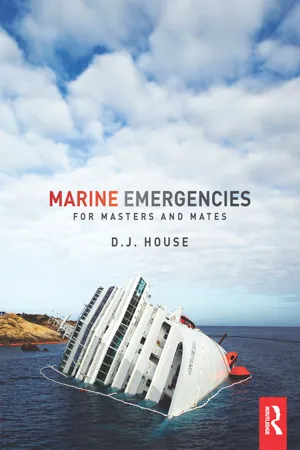

Peace of mind will certainly not occur until the ship’s Chief Officer provides the outcome from his initial damage assessment. Even then such a report may bring additional problems. Any Master will have the role of communications immediately following a collision, but he needs to know the subject matter of expected communications. We have already seen the catastrophic outcomes of mixed communications in the incident of the Costa Concordia.

Miscellaneous 1. Where a vessel has incurred collision in such a manner as to be left embedded into the other vessel, then it may be appropriate to leave the vessels in contact rather than separate the two ships. This could be achieved by maintaining a few revolutions on the engines of the striking vessel.

The reason not to separate is to retain one ship acting as a plug to the other and so reduce the permeability factor. Effectively this action could stop excessive flooding to the damaged vessel.

Another reason to stay in close contact could also be i...