![]()

EXPLORING SEX AND GENDER

Ignorance about women pervades academic disciplines in higher education, where the requirements for the degree seldom include thoughtful inquiry into the status of women, as part of the total human condition.

—Carolyn Sherif

Psychology has nothing to say about what women are really like, what they need and what they want, essentially, because psychology does not know.

—Naomi Weisstein

It may be a pleasure to be “we,” and it may be strategically imperative to struggle as “we,” but who, they ask, are “we”?

—Ann Snitow

We exist at moments, at the margins and among ourselves. Whether or not we have transformed the discipline of psychology, and whether or not we would like to, remain empirical and political questions.… At the level of theory, methods, politics, and activism, it is safe to say that feminist psychology has interrupted the discipline.

—Michelle Fine

It feels glorious to “reclaim an identity they taught [us] to despise.”

—Michelle Cliff

[A]s historians and sociologists have begun to identify the ways in which the development of scientific knowledge has been shaped by its particular social and political context, our understanding of science as a social process has grown.

—Evelyn Fox Keller

They say that women talk too much. If you have worked in Congress you know that the filibuster was invented by men.

—Clare Boothe Luce

If you are going to generalize about women, you’ll find yourself up to here in exceptions.

—Dolores Hitchens

Remember, Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, but she did it backwards and in high heels.

—Faith Whittlesey

DISTINCTION BETWEEN SEX AND GENDER

The Limits of Biology

Why Gender?

Beliefs about Gender

Gender Stereotypes

SEX DISCRIMINATION IN SOCIETY AND SCIENCE: BLATANT, SUBTLE, AND SCIENCE: BLATANT, SUBTLE, AND COVERT

Sex Discrimination in Society

Sex Discrimination in Science

FEMINIST PERSPECTIVES AND IDEOLOGY

Feminism: Not a “Brand Label”

THE FEMINIST CRITIQUE IN PSYCHOLOGY

Biases in Research

Traditional, Nonsexist, and Feminist Approaches to Research

Mapping Solutions for Gender-Fair Research

FORMAL RECOGNITION OF THE PSYCHOLOGY OF WOMEN

Ethnic Minority Women

EMERGENCE OF THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MEN AS A DISTINCT FIELD

PSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH AND SOCIAL CHANGE

SUMMARY

GLOSSARY

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

FURTHER READINGS

It has been more than 35 years since Sherif and Weisstein penned the preceding sentiments that reverberated throughout psychology. More recently, the field of the psychology of women has begun to correct its androcentric (male-centered) bias and the literature on the psychology of women continues to expand. One of the authors of this textbook, Florence Denmark, commented in 1980 that women in psychology had gone from “rocking the cradle to rocking the boat.” In fact, there are now several journals (Feminism and Psychology, Sex Roles, and The Psychology of Women Quarterly) exclusively concerned with women and gender. The psychology of women is also interdisciplinary because it is informed by research conducted across a wide number of disciplines, such as biology, sociology, anthropology, history, media studies, economics, education, and linguistics.

As Fine suggests in the preceding quote, however, “interrupting” the discipline of psychology means that psychology has been made to pause and reconsider its theoretical assumptions and where they have led us. This reconsideration is a first step in transforming the discipline and the social structures that have impeded the progress of women in society. Today women and the issues that they care about receive greater attention from scientists, researchers, and laypersons. Few would dispute that women have made great strides in North America over the last quarter century. Yet clearly not all women have thrived. Subtle, and sometimes not-so-subtle, forces continue to support belief systems, traditions, and practices that are sources of inequity between females and males.

In this chapter, we will discuss the distinctions between sex and gender. The chapter also explores and critically examines traditional approaches to psychological research and the biases therein. Psychological research, like any research enterprise, is subject to the perils of researchers’ own stereotypes and attitudes, which affect the way women and female psychologists are perceived. Sexism in both society and science is explored and gender-fair solutions for sexism in research will be considered. Feminist research, due to its critique of scientific procedures and findings, is particularly suited to uncovering biases that are related to race, ethnicity, disability, and sexual orientation as well as gender. Feminists in psychology have begun to focus on the societal forces that afford privilege for some at the expense of others. Therefore, feminist psychologists are positioned at the forefront of social change as they uncover bias in society and science and advance the study and understanding of girls and women.

To make psychology a stronger science and profession that better serve the public interest, certain changes are necessary. Specifically, sensitivity to issues concerning women, gender, and diversity must be emphasized. Psychology should include a gender perspective in its domains of science, practice, education, and public interest. Psychology must make visible women’s viewpoints and experiences. Engendering psychology refers to cultivating a psychology in which gender considerations are mainstreamed or integrated throughout the discipline (Denmark, 1994). In addition to distinguishing between sex and gender, this chapter will discuss the obstacles faced and the advances made in research as sensitivity to gender issues becomes more and more salient in psychology.

DISTINCTION BETWEEN SEX AND GENDER

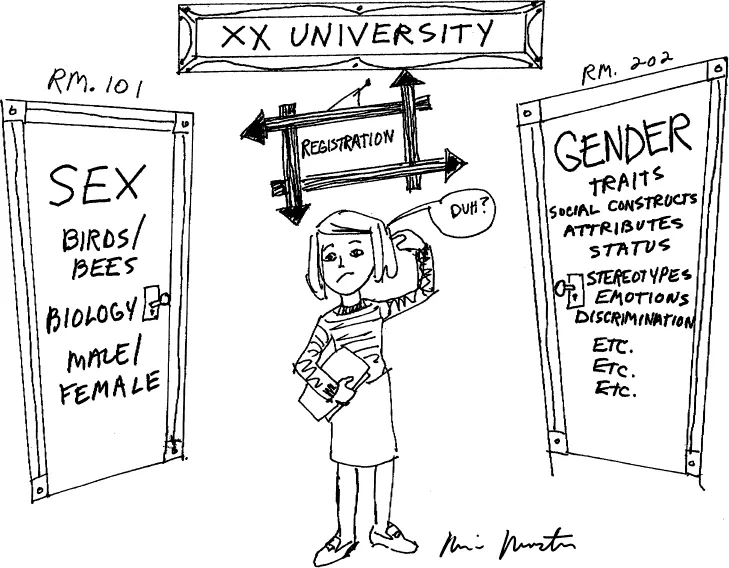

The girl pictured in Figure 1.1 is mystified by the distinction between sex and gender. Let us investigate the meanings of these terms to clear up her confusion.

The Limits of Biology

The terms sex and gender are often misunderstood and misused. All animals, including humans, are differentiated by sex, but only humans are differentiated by gender. Sex, very simply, refers to the biological differences in the genetic composition and reproductive structures and functions of men and women. Two biological sexes exist in mammals and in many non-mammalian species, although recent controversies question the actual number of biological sexes that exist (see Chapter 4).

Biological differences between females and males exist on many levels: chromosomal, genetic, hormonal, and neurological. There is widespread misinformation and lack of understanding of these processes and interrelationships. For example, people’s unfounded beliefs concerning hormones make the distinction of sex even more confusing. Many individuals believe that estrogen and progesterone are uniquely female hormones, while androgens are hormones that belong exclusively to males. However, all these hormones are found in both men and women, but in varying concentrations.

Why Gender?

Biological differences between men and women become social distinctions in most societies. Though gender is based on sex, it is actually comprised of traits, interests, and behaviors that societies place on or ascribe to each sex. In psychology as in all sciences, research findings are put into a theoretical framework to give meaning and coherence to facts and to generate future research. Two major theories with sharply contrasting perspectives currently vying for influence in the social sciences, including psychology, are sociobiology and social construction theory.

FIGURE 1.1 The Sex–Gender Distinction

Evolutionary psychology (or sociobiology) was first formulated by E. O. Wilson, who argued that psychological traits are selected in a population because they are adaptive and help maintain that population. In other words, psychological traits are subject to the same evolutionary processes as are physical traits, and natural selection helps shape aspects of social behavior and social thinking (Denmark, Rabinowitz, & Sechzer, 2000). Proponents of this view hold, for example, that women were bred to be mothers and men to be providers because the biological, sexually differentiated roles maximize the survival of the human species (Wilson, 1975). According to Wilson (1975), in early history, men were predominantly responsible for hunting in the wild, which required cognitive and motor skills such as mental rotation and good hand–eye coordination in order to be successful. Women, who were primarily in charge of raising and protecting children and gathering nearby fruits and vegetables, would have less need of such skills and thus did not develop them. Such differences are said to have impacted on the abilities and traits carried by men and women today (Denmark, Rabinowitz, & Sechzer, 2000). In Wilson’s own words:

It pays males to be aggressive, hasty, fickle, and undiscriminating. In theory it is more profitable for females to be coy, to hold back until they can identify the male with the best genes … human beings obey this biological principle faithfully. (1978, p. 156)

Evolutionary psychologists also propose that different preferences for males and females in regards to mate selection are biologically defined rather than culturally determined. For example, men place more emphasis on the physical attractiveness of their mates than do women, who are more interested in men’s ability to be providers (Buss, 1994). This has to do with the fact that men are often faced with the problem of identifying women who are fertile and healthy enough to bear offspring, which is thought to be associated with attractiveness, whereas women are concerned with finding a mate who is willing to provide for her and her child, a task that would be difficult for her to undertake alone.

Although evolutionary theory has gained some popularity, it is more important to note that the theory attempts to explain conditions only after the fact. The theory provides a possible explanation for events that occurred in the past, but is not amenable to testing. In addition, the theory overlooks data that do not support the evolutionary framework and fails to consider the fact that women also engage in tasks that required skills traditionally considered to be within the male domain, such as spatial abilities (Smuts, 1995).

The second theory, social constructionism, is often traced to French philosopher Michel Foucault (1978). In contrast to evolutionary theorists, social constructionists believe that human behavior is shaped by historical, cultural, and other environmental conditions rather than from a biological perspective. This view further suggests that human behavior does not have essential elements that have universal meanings across times, places, and circumstances. Thus, the meaning of behavior will also change across time and place. Behavior can be best understood by examining its historical, cultural, and social milieu. Throughout this text we will see the impact of social construction on gender. For instance, as we will see in Chapter 8, the meaning of a sexual act depends on the particular context in which it occurs. Thus, men who have sex with other men while they are in prison rarely consider themselves, or are considered by others, gay.

In an age of technological advancement in much of the Western industrial economies, the different life experiences of males and females are not due mainly to hormones or reproductive capacities, but primarily to the social context that determines gender, that is, what is considered “feminine” and what is “masculine.” By social context, we mean the total social sphere in which people find themselves: their personal history, immediate situation, society, and culture. The social context influences and determines the beliefs and behaviors that many people mistakenly believe are directly linked to being female or male. Gender is also more than just a category. Gender is a set of experiences and activities that comprises being female and male; and to a greater or lesser extent, all females and males are involved in the ongoing, dayto-day activities that make up “doing” gender (West & Zimmerman, 1987), or living up to society’s prescriptions for gender based on their sex.

Gender is a social construction that refers to how differences between girls and boys and women and men are created and explained by society. It refutes notions that most differences between women and men are due to biology and are normal and immutable. The concept of gender underscores the fact that while we may observe many different behaviors and attitudes between women and men, there is not necessarily a biological basis for those differences. For example, gender is quickly constructed, even for the newborn. A visit to a greeting card shop will demonstrate that foremost on the mind of those who congratulate new parents is the sex of the newborn. Girls’ cards are dominated by themes of daintiness and physical attractiveness. Boys’ cards are dominated by themes of strength and sports. The difference between the types of cards for female and male infants reveals how early gender is constructed, and how the ideals for each sex are based on images that maximize the differences between females and males. For example, within 24 hours of birth, mothers and fathers were more likely to describe female infants as softer, finer featured, and smaller than male infants eve...