Point of departure: Los Angeles

Edward Soja opens his book Seeking Spatial Justice with what he calls “a remarkable moment in American urban history” (Soja 2010, p. vii). In October 1996, in a courtroom in downtown Los Angeles, a lawsuit brought against the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) by a coalition of grassroots organizations was resolved in an unprecedented consent decree. It was decided that, for at least the next ten years, the MTA would have to give their highest budget priority to improving the bus system that was (and still is) primarily serving the transit-dependent urban poor. According to the decision, the transit authority was required to purchase new buses accessible to wheelchair users, reduce overcrowding on buses, freeze fare structures, enhance bus security, reduce bus stop crime, and provide special services to facilitate accessibility to jobs, education, and health centers. As Soja states, “if followed to the letter, these requirements would soak up almost the entire operating budget of the MTA, making it impossible to continue its ambitious plans at that time to build an extensive fixed rail network” (Soja 2010, pp. vii-viii).

The direct cause that sparked the lawsuit was a proposal of MTA in early 1994 to raise the bus fare from $1.10 to $1.35, eliminate the monthly passes used by many poor bus riders, and cut service on several bus lines. In response to this proposal, the Labor/Community Strategy Center, a community organization and think-tank addressing concerns at the intersection of ecology, civil rights, and workers’ and immigrants’ rights, mobilized bus riders to demonstrate at a public hearing. In spite of this protest, the MTA board approved the original proposal in June 1994. The final spark for the lawsuit occurred just seven days later, when the MTA board voted to spend an additional $123 million on the next phase of an extensive rail program that was primarily serving the affluent suburban population of the larger Los Angeles metropolitan area (Grengs 2002).

Following this highly controversial MTA decision, the Labor/ Community Strategy Center formed the Bus Riders Union, which was initially composed of 1,500 dues-paying members, mostly low-income bus riders. The Bus Riders Union built a mass base by conducting recruitment campaigns directly on the buses. In parallel, the movement brought on board a range of other organizations, including Justice for Janitors, the Filipino Workers Center, and the Korean Immigrant Workers Advocates. This broad coalition eventually filed the lawsuit against the MTA on behalf of 350,000 bus riders (Grengs 2002).

In the lawsuit the grassroots coalition drew on various arguments. They argued, first and foremost, that the decision of MTA to give priority to the development of an extensive rail network constituted a racist practice. In a parallel to the famous legal case about racial practices in education (the Brown vs. Board of Education case, dating back to 1954), it was argued that poor ethnic minorities living in urban centers were being denied their rights by the existence of “two separate but unequal systems” in the provision of mass transit, arguably a vital urban service particularly for the poor (Soja 2010, p. viii). While the transportation needs of poor and ethnic minority populations were never entirely ignored by transportation planners, either in Los Angeles or elsewhere, the coalition of grassroots organizations argued powerfully that these needs “were systematically subordinated to the needs and expectations of those living well above the poverty line” (Soja 2010, p. x). Indeed, as the coalition showed, although 94 percent of MTA’s customers were bus riders, the MTA was spending 70 percent of its budget on the 6 percent of its ridership that were rail passengers (Grengs 2002).

The coalition also explicitly linked their cause to the environmental justice movement, which emerged in the USA in the 1970s and 1980s and emphasized the role of space in the injustices befalling poor and ethnic minorities due to environmentally polluting facilities and practices. Drawing on the arguments championed by this movement, the coalition argued that the MTA practices constituted a form of discrimination based on place of residence, claiming that where one lived should not have negative repercussions on important aspects of daily life as well as personal health (Soja 2010, p. viii). Furthermore, the coalition revealed the vast disparities in subsidies going to different types of public transport service, showing how each trip by rail, predominantly used by white and affluent travelers, was subsidized at a rate of more than $21, while the figure was a little over $1 per bus trip, used primarily by the urban poor (Soja 2010, pp. xiv-xv; see also Grengs 2002).

The lawsuit was an exceptionally successful case of grassroots activism, not least because the resulting decree was radically progressive in character, as Soja underlines: “Giving such priority to the needs of the inner-city and largely minority working poor was a stunning reversal of the conventional workings of urban government and planning, as service provision almost always favored wealthier residents even in the name of alleviating poverty” (Soja 2010, p. viii). Indeed, in its essence the decree implied the transfer of billions of dollars from a plan that disproportionately favored affluent suburbanites to a plan that worked more to the benefit of the poor, ethnic minorities and transit-dependent populations.

Seeking transportation justice

The Los Angeles lawsuit powerfully exposes the inherently political decisions that constitute the very essence of transportation planning and policy. Transportation planning is inevitably political because interventions in the transportation system always affect different persons in different ways. However, in the everyday practices of transportation planning across the world, their political character often disappears into the background (with some notable exceptions, such as Cleveland’s experiences with equity planning in the 1970s; see Krumholz 1982). Typically, mostly well-intentioned planners and engineers follow professionally accepted procedures to analyze the state of the transportation system and to develop solutions to alleged problems such as road congestion, air pollution, increasing costs, or poor service levels. The way in which these solutions work out for different persons, and the often systematic way in which they affect different persons, are routinely ignored in the practice of transportation planning. It was only because of the blatant disparities in the Los Angeles case, between the urban poor and the suburban rich and between a neglected bus service and a flagship rail project, that the inevitably political nature of transportation planning could be so clearly exposed.

The Los Angeles case thus powerfully illustrates the inevitable political choices and trade-offs that have to be made in transportation planning and policy. Let me highlight three crucial domains of choice, all intricately related to differences between persons: place of residence, level of income, and abilities and skills.

The first issue that emerges from the Los Angeles case is the role of place. The grassroots coalitions argued that place of residence should not determine a person’s quality of life. Yet transportation systems, by their very nature, are bounded in space. They provide service to some jurisdictions and thus to some persons, while hardly providing benefits to other jurisdictions or other persons. It is by no means clear how transportation planning should take this inevitable spatial dimension into account. Should transportation planning seek to provide the same level of service to all persons, irrespective of their place of residence? In other words, should a largely comparable transportation system be provided over an entire metropolitan area or region? And, if so, does this imply that transportation facilities should be heavily subsidized in peri-urban and rural peripheries, where there are fewer persons to shoulder the costs of transportation facilities? Or is it legitimate to provide higher levels of service in urban centers, while providing less service on the periphery, thereby avoiding the necessity of cross-subsidization between areas? And how should ‘service’ be defined in a spatially diverse context? Should it be defined in terms of kilometers of road space per inhabitant, in terms of travel speeds on the transportation network, or in any other way? Should all persons be provided with the same range of choice between different transportation services, irrespective of residential location? Is it at all legitimate to expand the transportation choices in some areas while reducing the level of choice in other areas? These questions clearly played a role in Los Angeles, where sparse but highly subsidized, high quality rail services were provided to suburban residents, while basic bus services were delivered to urban residents living in relatively high-concentration areas. What, if anything, could warrant such apparent spatial disparities in financial support and service quality? And, if the Los Angeles disparities are not warranted, what other kinds of differences between areas could be justified?

The second key issue that emerges from the Los Angeles case relates to the pricing of transportation services. Since incomes vary strongly between persons in virtually every society, the pricing of transportation services will affect persons in different ways. Since pricing policies also strongly shape who can and will use what kind of transportation service, and thus who can and cannot access destinations and thus activities, the issue is fundamental to transportation planning. Multiple questions emerge here. Should transportation infrastructures and services be seen as a regular private good to be sold against market prices? In other words, should all travelers pay the full costs of their journeys? Or are there valid reasons to subsidize travel? If so, what makes transportation infrastructures and services different from other services, like restaurants, cinemas or health clubs? And if it is justified to subsidize travel, should all travel receive a subsidy or should subsidies be targeted to particular groups? Which groups would that be? Is it justified to subsidize public transport services, while requiring car users to pay the full price of travel? Can a subsidy on transportation fuel or even car ownership be warranted? If so, under what circumstances? Should transportation budgets be distributed evenly over the population? Clearly, the Los Angeles decree has hardly provided a satisfactory answer to any of these questions. The decree did not challenge the large subsidies for rail travel, while it did accept a small fare increase for the bus services. Moreover, no explicit argument was given justifying the continuation of these disparities. The questions thus remain out in the open.

Finally, while less prominently featuring in the Los Angeles case, persons differ fundamentally in their abilities to use various modes of transportation. For instance, in developed countries over one percent of the population suffers from various forms of visual impairments, which often inhibit persons from driving or cycling independently. Likewise, public transport services are often not accessible to persons using a wheelchair or experiencing particular types of travel-related impairments. But also more subtle exclusionary mechanisms may be at play, as when concerns about traffic safety prevent persons and particularly women from cycling, or when concerns about personal safety inhibit persons, for instance older persons or children, from using particular public transport services at particular times of the day. Clearly, any mode of transportation assumes particular skills and abilities and every transportation mode, even walking, is thus likely to exclude some people while bringing advantage to others. These differences in persons’ abilities to use transportation modes turn transportation planning into a profoundly political exercise, as it implies that difficult trade-offs have to be made. Should transportation planning give priority to investment in the most inclusive transportation modes as opposed to transportation modes that exclude a substantial share of the population? Or should transportation planning seek to design and deliver a system that can offer the cheapest service to most people, according to the famous dictum ‘the greatest good for the greatest numbers’? If important transportation modes cannot be used by all persons, because of differences in persons’ abilities, what kind of differences in service level between various transportation modes are acceptable? What would justify these differences, apart from technical considerations?

These difficult trade-offs are not unique to the Los Angeles case, the USA, or even large cities in the ‘developed’ world. They are likely to play a key role anywhere in the practice of transportation planning, whether in large cities or small towns, at the local level or at the national scale, in the Global North or the Global South. It is only because transportation planning is typically presented as the technical exercise of providing a well-functioning transportation system to society that these trade-offs often fail to reach the public eye or enter the public debate. But governments, as elected bodies that have been endowed with the primary responsibility for the operation, maintenance and development of the transportation system, cannot simply ignore these difficult choices when they present their transportation plans. It may be expected from well-functioning governments that they openly engage in these difficult trade-offs and explicitly justify the choices they make. And such a justification is not possible without reverting to notions of justice and fairness. Like any other form of public planning, transportation planning is thus inevitably a normative activity. It follows that the core question of this book is not whether transportation planning should be based on principles of justice, but on which principles of justice it should be based.

It is my ambition with this book to answer this question. I aim to contribute to the search for transportation justice by developing explicit principles of justice for transportation planning, drawing on both philosophies of justice and the particularities of transportation. Formulated in more ambitious terms, my aim is to develop a new paradigm, or comprehensive theory, for transportation planning, based on principles of justice.

What kind of theory?

The aim of this book is to develop a theory of fairness in the domain of transportation. This ambition requires further specification as to what type of theory I intend to develop. For this purpose, it is useful to draw on the classical distinction between procedural and substantive theories on the one hand, and empirical versus normative theories on the other (Yiftachel 1989).

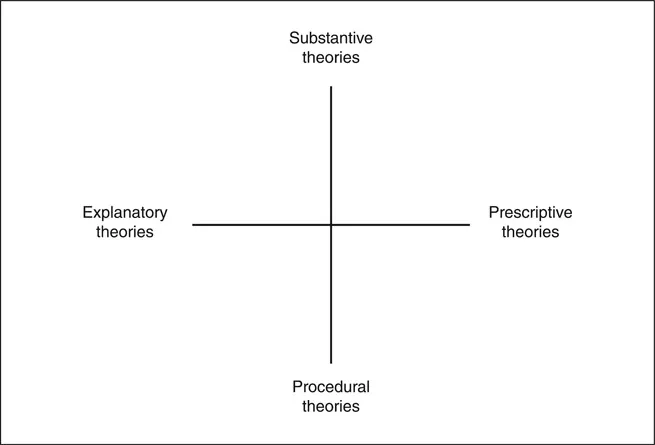

The distinction between procedural and substantive theories of planning was pioneered by Faludi (1973). He argued that it was of essential importance for the discipline of (urban) planning to make a systematic distinction between both types of theories, terming them theories of planning and theories in planning, respectively. Procedural theories relate to the process and methods of decision-making, whereas substantive theories pertain to the (interdisciplinary) knowledge relevant to the content of planning, that is, relevant to the understanding of land use dynamics (Yiftachel 1989). The distinction between empirical and prescriptive theories was introduced implicitly by a number of authors and made explicit by Yiftachel (1989). Empirical or explanatory theories seek to understand the ‘real world’ as it is out there; in other words, they seek to understand and explain how the world is. Prescriptive theories, in turn, provide abstract and general guidance on how the world should be; in others words, they provide guidance for action and intervention. By juxtaposing these two distinctions, four types of theories can be distinguished (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Four types of theories.

The theory to be developed in this book is both substantive and prescriptive in nature (i.e., it belongs to the top-right quadrant in Figure 1.1). The focus on fairness and justice inevitably puts it firmly in the domain of prescriptive theories. The aim is to develop a theory that is helpful in the normative assessment of the transportation system. The theory is substantive in nature because it seeks to define what is a fair transportation s...