![]()

PART I

THE ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION

OF HEALING GARDENS

![]()

The history

What were gardens for?

Gardens as havens, gardens for health

E. O. Wilson, father of the biophilia hypothesis, says our sense of belonging today comes from time in city parks, from choices we make for habitation, for where we spend our leisure time; time spent in gardens provokes deep memories of our evolutionary time on the African savannah. Wilson believes we are hard-wired to need nature around us, that it is within our genetic make-up that we are part of nature. Since he wrote Biophilia in 1984 and co-edited The Biophilia Hypothesis in 1993, around the world much research time and effort has gone into proving the case for our need to be surrounded by living things. This deep need is a core part of our being that when denied affects us in multiple ways.

‘If there is an evolutionary basis for biophilia, then contact with nature is a basic human need: not a cultural amenity, not an individual preference, but a universal primary need. Just as we need healthy food and regular exercise to flourish, we need on-going connections with the natural world.’

Judith Heerwagen, Ph.D.

As places to connect with nature within an urban framework, healing gardens are part of that universal primary need. The relationship between children’s ability to learn, our social relations, our productivity at work, our propensity to commit crime and indulge in self-harming lifestyle behaviours, our appreciation and stewardship of the environment and our psychological and physical health, have all been studied in relation to time spent outdoors in nature. Wilson explains:

All these things are intertwined, and so we have to learn how to look at them as one combined, nonlinear process that’s just about going to bear us away unless we handle them now as a whole … And if we do it, there’s going to be light at the end of that tunnel. We’ll be so much better off.

(Tyson, 2008)

Figure 1.1 Healing water garden, Surrey, UK.

Design for health and well-being requires us to focus first on where we have come from. In order to plan our way forward it is therefore helpful to look to the wisdom of the past. Indigenous peoples of North America, ancient wisdom from China, early philosophers and religious teachings from Europe and elsewhere, all look to the spiritual nature of the land, and its capacity to heal. When surrounded by the beauty, the power and the majesty of nature, our sense of awe and wonder is evoked. It is nature’s capacity to inspire, to give peace, to heal, to balance life, that we value when we set out to create new landscapes.

Creating gardens and gardening (the tending of gardens and rearing of plants), along with animal husbandry, was one of our earliest forms of taming nature, bending it to our will. Early gardens were a simplification of Mother Nature herself, formed for the benefit of people but with few modifications of the natural form. Propagation of hybrids and elaborate training and cultivation techniques came later. Natural elements within the garden included flowers, shrubs and all-important trees. Trees were originally planted to provide shade, fruit and to uplift the soul through a view up through a tracery of leaves.

Today we talk about health spas being like ‘an oasis in the city’. Early gardens often fitted the description of an oasis. The gardens were leafy, compact, welcoming spaces, developed around a water supply. Resources were scarce and from that scarcity came an understanding of and an appreciation for the need to work with nature, to grow what naturally grew in the local climate, that soil. The gardens were intimate spaces, at a scale easy to tend and comprehend. By being a smaller scale version of the wider landscape, early gardens were presented in a form able to be appreciated and understood by people regardless of age, ability or education.

Medieval gardens were about beauty and respite from the harsh world beyond the garden perimeter. Frequently walled to keep out wild animals or marauding bandits, the gardens had an aesthetic that did more than just green and cool the space. Symmetry and line were balanced with a profusion of plants. The eye was eased down an axis, with resting points along the way.

Figure 1.2 Date palms’ tracery of leaves, Dubai.

Figure 1.3 Pergola perspective, Wisley Gardens, UK.

Initially, using locally available materials, structures were built for the plants to grow over. As communities and economies began to expand, trading allowed for unusual and prized imported materials to be used within the gardens. These small buildings, arbours, pergolas and arches, were used to provide perspective, shade and frame views. In time some gardens evolved as a display of wealth. Most gardens, however, were necessarily low maintenance, as few people could afford the luxury of time to tend a purely decorative garden. They needed to grow plants and tend animals for food. Culinary herbs and vegetables were regularly mixed into herbaceous plantings. The mixed plantings enhanced the low maintenance aspect of the gardens by attracting beneficial insects and pollinators and reducing the risk of major outbreaks of pest infestation or disease. Interestingly that ‘fashion’ of mixing herbs and flowers, practicality with beauty, is becoming popular again today.

Gardens, like most art forms, are heavily influenced by their moment in history. The level of cultural and spiritual enlightenment at the time in large part determines the style of garden.

Evidence in paintings and models provides information about our first gardens, such as we know them today, in Egypt. Early Egyptian gardens grew food and flowers, laid out as temple gardens and domestic gardens. Lilies and roses were also grown by the ancient Egyptians for perfume as an early form of commercial horticulture.

Figure 1.4 Wellington Botanical Gardens, New Zealand: Edible edging – parsley and tulips.

In China, Italy and Greece there is evidence of gardens 5,000 years ago. In China, however, the ‘gardens’ were more vast royal parks than intimate growing spaces. Smaller temple and domestic gardens came later.

As culture grew so did an appreciation of plants. We learnt how to grow them out of their natural habitat, and developed decorative containers to house them. Over time we placed symbolic sculpture and pots within natural plantings, developed tiled paths and terraces with intricate detailing in colours complementary to the plantings. While practical, the durable surface was also beautiful.

The gardens were relaxing havens, where people could go to ‘take the air’, walk, sit, pick and eat fruit, admire the colour, scents and sounds of nature.

History is rich with references to gardens and the people’s close relationship to and with the affirming, sustaining, and health-giving properties of nature. Today though, how often do we forget the essence of a garden, that basic nature, that ability to heal, when we come to a design project? It has almost become the norm to allow ourselves to be driven by deadlines and budgets to the point where we forget what landscape and nature is about. We have become accustomed to seeing a design or a development scheme that looks good on paper but in reality takes its reference more from ‘commercial realities’ and the built environment than the natural environment to which we were originally so attracted.

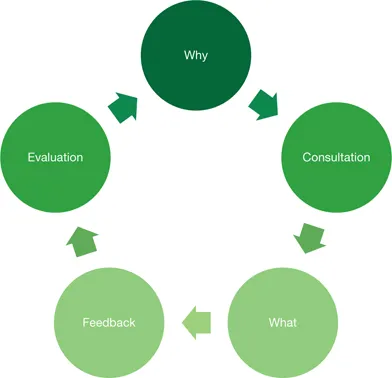

Driven by desires for ‘bigger, brighter, better’, it is easy to forget why we are working on a project before contemplating what we are trying to achieve.

Figure 1.5 Tiled garden, Marrakech, Morocco.

Figure 1.6 Container grown plants, Marrakech, Morocco.

Figure 1.7 The design cycle.

Ancient to modern healing, sensory and therapeutic gardens

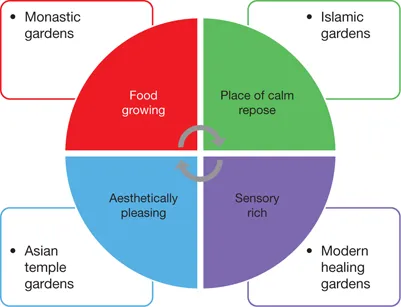

When looking to create healing gardens today, it is helpful to consider the healing gardens of yesterday. If we take two of the world’s major religions as offering examples of early garden forms, as early as 1,500 years ago we see walled Islamic gardens and monastic cloister gardens being used as healing gardens. Designed and constructed to sustain the local community, the origin of today’s model for salutogenic sustainable living can be traced to these gardens. Aiding health and wellbeing in a time of pestilence and strife, monastic and Islamic gardens shared many characteristics. Based on the belief in paradise on earth, the concept of a paradise garden is an ancient one, pre-dating the three great monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, by centuries. These were early sensory gardens.

Paradise gardens

Islamic gardens referenced paradise through the Garden of Eden, with the ‘river of life’ flowing under the garden in irrigating, cooling rills. Fruit trees provided welcome shade as well as food. The fruit blossom provided fragrance, colour and general delight while also attracting beneficial birds, bees and insects. Gardens were laid indoors and out in a pleasing symmetrical fashion, where nothing jarred the eye but rather presented a balanced, calming view. They echoed the fundamental principle that this world is a reflection of a heavenly realm.

From early on in the Jewish and Christian traditions, ‘paradise’ became associated with the Garden of Eden. Prior even to that, the pre-Islamic Arabs considered the slightest indication of nature’s greenness to be sacred. Since people were completely dependent on the oases for their survival it was natural that they should love and revere nature’s vegetation, both for its physical benefits and as a sign of the mysterious power that guided the universe.

Figure 1.8 Historic religious gardens matrix.

Figure 1.9 Indoor water garden, Marrakech, Morocco.

This sense of mystery is an important element in garden design that we will come back to throughout the text. Gardens and nature have held and continue to hold a deep spiritual appeal, albeit sometimes on an unconscious level, for many people today. Although by nature humans are suspicious of things they cannot see or understand, we accept simple gardens and wider nature on a deep level, without need or desire to question. When we are in a garden, what bliss not to have to think for a moment! However we define paradise today, a blissful state of being forms a large part of the image. Gardens today, however contemporary in styling, must still reference their origins if they are to be the healing, therapeutic spaces they can be.

The early paradise garden was a private space, hidden away as a place for quiet contemplation. In Persia, as well as in the...