![]()

1

Phonological Awareness and Reading

What is phonological awareness?

Virtually any three or four year old child understands a simple, spoken word like “cat”, but if you ask her about the sounds in that word she will be hard put to it to answer your question. Most children of this age would not be able to tell you what the word’s middle sound is, for example, or how the word ends. When children learn to talk, their interest naturally is in the meaning of the words that they speak and hear. The fact that these words can be analysed in a different way – that each word consists of a unique sequence of identifiable sounds – is of little importance to them. They want to know the meaning of what someone else is saying, and they need be no more concerned with the actual sounds that make up each word when they listen to someone speaking than they are with the exact composition of the food that they eat each day.

In a year or so, however, these children have to learn to read and write words as well as to speak them, and that may mean that the component sounds in these words take on a new significance. Alphabetic letters represent sounds, and strings of letters, by representing a sequence of sounds, can signify spoken words. The letters “c” “a” “t” represent sounds which roughly add up to the word “cat”. So, a child who is being taught to read English, German, Portuguese or any other alphabetic script may have to pay a great deal of attention to a word’s sounds.

But it need not be so. The fact that individual alphabetic letters represent sounds does not necessarily mean that children learn to read words like “cat” by working out the individual sounds represented by each letter and then putting these sounds together. The child may, to take just one other possibility, recognise the word as a visual pattern without paying a great deal of attention to the individual letters or to the sounds that they represent.

We cannot assume, therefore, that children’s awareness of sounds – or “phonological awareness”, as it is often called – plays an important part when they learn to read and write. We have to establish by empirical means whether this connection exists or not and what form it takes. We need to discover if children are helped, and perhaps hindered sometimes, by their sensitivity to the constituent sounds in words.

One useful starting point in this quest is to recognise that “phonological awareness” is itself a blanket term. There may well be different forms of this kind of awareness, because there are different ways in which words and syllables can be divided up into smaller units of sound.

Phonemes and other speech units

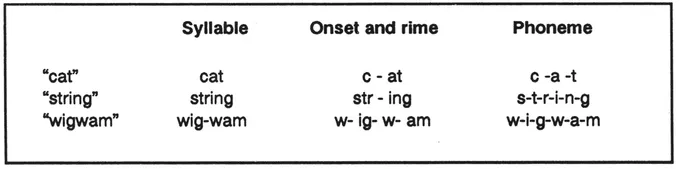

There are at least three ways of breaking up a word into its constituent sounds, and thus at least three possible forms of phonological awareness. Figure 1.1 shows what these are.

Syllables. The first and perhaps the most obvious way is to break it up into its syllables. This poses very little difficulty for most children (Liberman, Shankweiler, Fischer & Carter, 1974). However, many words and particularly words which children first learn to read, are monosyllabic, and so awareness of syllables cannot be relevant to the constituent sounds of these words. We need to think of smaller units than the syllable.

Phonemes. The second way does involve much smaller phonological segments. It is to divide words into phonemes. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that can change the meaning of a word. “Cat” and “mat” sound different and have different meanings because they differ in terms of one phoneme. Alphabetic letters typically represent phonemes, and thus strings of alphabetic letters represent sequences of phonemes. In order to see that a sequence of letters adds up to a meaningful word because it represents all the phonemes in that word, the child has to understand how that word is in effect a collection of phonemes.

FIGURE 1.1 Three ways to divide words into component sounds.

The importance to the child of learning how to use the relationships between single letters and single phonemes, or “grapheme-phoneme” correspondences as these relationships are often called, has been widely recognised. Indeed, some people concerned with phonological awareness and its relation to children’s success in learning to read have stopped here. In their view, awareness of phonemes plays a crucial role in learning to read and no other form of phonological awareness has much significance.

Intra-syllabic Units – Onset and Rime. Yet there is a third and intermediate kind of phonological awareness and we ought to consider whether it too has any part to play in children’s reading. Words can also be divided up into units that are larger than the single phoneme – units which themselves consist of two or more phonemes – but smaller than the syllable. It is usually possible to divide a syllable into two parts, an opening and an end section. The word “string”, for example, has a clear beginning in its first three consonants, “str”, and an equally clear end section which contains the vowel and the last two consonants, “ing”. This monosyllabic word, therefore, can be broken up into two phonological units, each made up of more than one phoneme. Units of this sort lie somewhere between a phoneme and a syllable, and are sometimes called “intra-syllabic units”. The opening unit is often called “the onset” and the end unit “the rime”.

There is a good reason for calling the end unit “the rime”. Words rhyme when they share common rimes. “String” rhymes with “wing” and with “thing”, and all three words have the same rime. This intrasyllabic unit therefore has an immense significance: rhyme is an extremely important part of our everyday lives. Rhymes are to be found practically everywhere – in poems, in songs, in advertisements and in political slogans. They are also a significant part of young children’s lives. Long before children go to school, they are taught rhymes, and begin to make up their own (Chukovsky, 1963; Dowker, 1989; MacLean, Bryant & Bradley, 1987).

Just as the rime tends to consist of two or more phonemes, so the written version of this speech sound usually contains more than one letter. The sound which “cat” and “hat” share contains two phonemes: but these words share a common spelling sequence “-at” which represents the shared sound, and that sequence consists of two letters. So if children connect rhyming sounds with reading, the connection will be between particular sounds and sequences of letters.

At this point we ought to return to our central term “phonological awareness”. Obviously someone who can explicitly report the sounds in any word is “aware” phonologically. But we have begun to extend the use of the term “awareness” by introducing the subject of rhyme. In our view, a child who recognises that two words rhyme and therefore have a sound in common must possess a degree of phonological awareness, even if it is not certain that this child can say exactly what is the sound that these words share. To know that there are categories of words (“cat”, “hat” and “mat”) which end with the same sound is a form of phonological awareness.

We now have two possible links between the constituent sounds in monosyllabic words and alphabetic letters. The first is the link between single letters and sounds which are usually phonemes, and the second is the link between the speech units, onset and rime, which often contain more than one phoneme and also are represented by a letter sequence like “-at” or “-ight” or “-ing”. The difference between these two possible connections between phonological awareness and reading will play an important role in our book.

Cause and effect in the relationships between phonological awareness and reading

We will show later that there is plenty of evidence for a connection between children’s reading and their awareness of sounds. The better they are at reading, the more sensitive they seem to be to a word’s constituent sounds. But connections of this sort always raise questions of cause and effect. There are at least two possibilities.

One is that children learn how to divide words up into their constituent sounds because they are taught to do so when they learn to read. In this case the experience of learning to read would be the cause of phonological awareness. The second possibility is that cause and effect go the other way round. Before children learn to read, they may build up phonological skills which then affect how well they learn to read.

Predictions

At first sight the two alternatives seem equally plausible. We can think of no pressing a priori reasons for preferring one hypothesis over the other. But at least one can find out which is right, for the two hypotheses produce radically different predictions.

1. Illiterate and literate groups. One sharp difference between the two hypotheses is that they produce different predictions about people who have never learned to read. If reading is the main cause of phonological awareness, illiterates should be quite unable to succeed in tasks which test their awareness of sounds. Literate people, in contrast, should find these phonological tasks quite easy. On the other hand, if phonological awareness precedes reading then illiterate people should be as good in phonological tasks as anyone else.

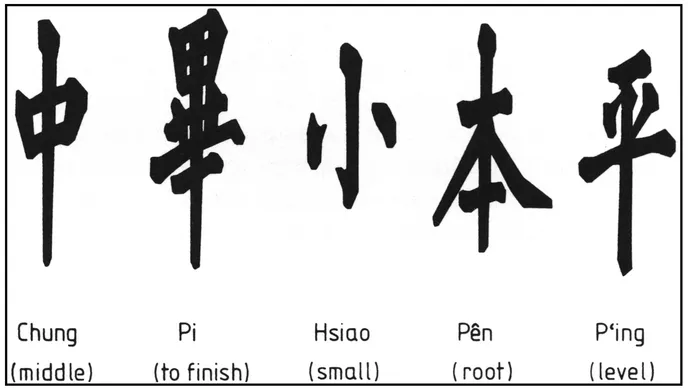

2. Logographic and alphabetic groups. Another way of distinguishing between the two hypotheses is to look at people who have not learned an alphabetic language – at those, for example, who have learned a script such as Chinese in which each word is represented by its own distinctive shape (a logogram), (see Fig. 1.2.) According to the first hypothesis (reading causes phonological awareness), there should be a considerable difference between these people who have learned a logographic script and thus have not been taught to divide words into sounds and others who have learned an alphabetic script: the “logographic” group should fare much worse than the “alphabetic group” in phonological tasks. But if the second hypothesis (phonological awareness affects reading) is right, there is no reason for this sort of difference between the two groups: the logographic group should have the same phonological skills as those who have learned an alphabetic script. However, we have to be a bit cautious here, because the comparison is not a pure one. Some of the traditional Chinese characters contain “phonetics” which indicate part of their sound.

3. Younger and older children. So far we have only talked about special groups (if millions of Chinese readers can be called a special group). But, the two hypotheses also lead to radically different predictions about the course of development of phonological skills during childhood. Causes should precede effects, and so if children become aware of sounds as a direct result of being taught to read they should show no signs of phonological awareness until they have made some headway with reading. But, according to the alternative hypothesis that children’s phonological awareness has an effect on the way that they learn to read, they should be able to segment words into sounds before they learn to read.

FIGURE 1.2 Examples of Chinese characters.

1. Data on illiterate people

There would be little point in comparing illiterate with literate people in a country like England, where instruction in reading is readily available, and illiteracy comparatively unusual. In such a country illiterate people may well have other problems than just a failure to read, and so any difference between a literate and an illiterate group may have nothing to do with reading as such, and may simply reflect social and economic differences. However, there are many countries where illiteracy is more common, and the teaching of reading less widespread. In these countries it is easier to find groups of literate and illiterate people who are like each other in every way except that the people in one group can read and those in the other cannot.

One such country used to be Portugal in the 1970s before the time of a radical and effective programme to remove the problem of illiteracy. At that time Morais, Cary, Alegria and Bertelson (1979) studied a group of Portuguese illiterates and compared them to a similar group of adults who had been illiterate but had learned to read in adult literacy programmes. The experimenters gave both groups two tasks. One was to add a sound to a word (“alhaco”-“palhaco”), and the other to subtract a sound from a word (“purso”-“urso”). These examples are real meaningful words, but some of the addition and deletion problems involved made-up nonsense words.

Although the people in the illiterate group were able to manage some of the words (46% success in the addition task with real words), they made many more mistakes in the phonological tasks than the literate people did. The illiterate people did particularly badly when nonsense words were involved. One can note straightaway that at the very least this remarkable study demonstrates that one cannot take phonological awareness for granted. Here was a group of effective and competent adults who were strikingly insensitive to distinctions which most of us find transparently obvious.

Morais and his colleagues concluded that this was good evidence for the first of the two possible hypotheses, that people become aware of the sounds in words as a result of learning to read. However, we should like to suggest some reasons for caution about the authors’ main conclusion. The first is that one cannot be sure that the two groups were equivalent in every way apart from the fact that those in one could read and those in the other could not. It seems unlikely that pure chance alone determined whether or not these people took adult literacy courses. There could certainly have been some self-selection, and that could have been influenced by the people’s different abilities.

The second worry is that the biggest difference between the two groups was in the nonsense word condition. This raises the possibility that their problem was not so much with the business of adding and deleting phonemes, but with nonsense words per se. We need to give these people other tasks which involve nonsense words but no phonological analysis. According to the Morais et al. (1979) hypothesis the illiterates would have no particular difficulty in such tasks.

The third and most troublesome problem with the study is that all the tasks in it involved judgements about phonemes: for that reason the experiment is not a good test of the hypothesis about awareness of phonemes. The fact that the illiterate people were worse in all four tasks may mean, as the authors claim, that they have a specific insensitivity to phonemes, but it could also mean that they are worse at manipulating anything or at understanding instructions or at paying attention or even at caring how well they did. Single condition experiments are not the right way to test specific hypotheses.

Fortunately, the Brussels group has gone a long way towards checking that the effects are specific ones in another experiment in which they did include conditions which did not involve phonemes (Morais, Cluytens, Alegria & Content, 1986a). Once again they compared a group of illiterate Portuguese people to others who also had been illiterate but who by that time had with varying degrees of success completed a literacy course. The people in both groups were given a set of tasks, some of which involved phonemes and others not. The experimenters’ prediction was that the illiterate group would be at a large disadvantage in the phoneme tasks, but no worse than the literate group in the other conditions.

The experiment was a complicated one, because all the people being studied in it were given several tasks. The most interesting comparisons were between tasks in which the unit was the phoneme and others in which it was the syllable. One of these comparisons was between two “deletion” tasks; all the people were given both a phoneme and a syllable deletion task. These were somewhat limited tasks since they involved only nonsense words and the unit to be detached – phoneme or syllable – was always the same one. In the phoneme task the subjects were given a series of nonsense words beginning with “p” and had to work out what they would sound like without that opening consonant. In the syllable task the opening sound that had to be removed was the vowel “u” (this vowel was always followed by a consonant, and so its removal did shorten the word by a whole syllable).

The illiterate people were worse than the others at both tasks, but they were at a much greater disadvantage in the phoneme task than they were in the syllable task. This, the authors concluded, showed that illiterate people are relatively insensitive to phonemes. But one needs to be cautious about this conclusion too.

For one thing it is a pity that Morais and his colleagues used only nonsense words because these seem to give a particularly low estimate of illiterate people’s sensitivity to phonemes. For another, the phoneme that had to be deleted was always a consonant and yet the syllable that had to be deleted was always a vowel. Because of this the difference between the two tasks may have been nothing to do with phonemes and syllables; the illiterates might simply have found it ea...