![]()

1 Introduction to the challenge of pain and communication in disorders of consciousness

Camille Chatelle,1 Stev en Laureys,2 and Caroline Schnakers3

Abbreviations

| BCI | brain-computer interface |

| CRS-R | Coma Recovery Scale-Revised |

| DOC | disorders of consciousness |

| EEG | electroencephalography |

| fMRI | functional magnetic resonance imagery |

| LIS | locked-in syndrome |

| MCS | minimally conscious state |

| MCS+ | minimally conscious state plus |

| MCS- | minimally conscious state minus |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| VS/UWS | vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome |

Advances in medicine for resuscitation and care have led to an increased number of patients surviving severe brain damage. Some of them will quickly recover consciousness and will be able to communicate, while others may evolve into various disorders of consciousness (DOC). In this introductory chapter, we will define the different DOC that can follow a severe brain injury and the clinical challenges associated with these patients in terms of pain management and detection of consciousness and communication.

Behavioral definition of DOC following a severe brain injury

Although no commonly shared definition of consciousness exists, it is widely accepted that it is a multicomponent term involving a series of cognitive processes such as attention and memory (Baars, Ramsey, & Laureys, 2003; Zeman, 2005). It has been suggested that consciousness is underlined by a large frontoparietal network, also called the global neuronal workspace (Baars, 2005; Dehaene & Changeux, 2011). Additionally, neuroimaging studies have highlighted the importance of the thalamo-cortical connections, especially in the emergence of consciousness (Tononi & Koch, 2008). Indeed, in patients who have recovered consciousness, a reestablishment of the correlation between associative cortices and the thalamus has been observed (Laureys et al., 2000b).

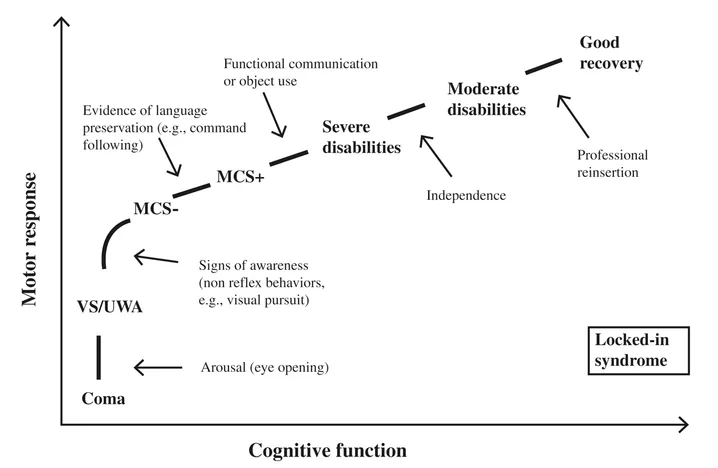

Figure 1.1 Different clinical entities encountered on the gradual recovery from coma, illustrated as a function of cognitive and motor ability (adapted from Chatelle & Laureys, 2011).

At the bedside, consciousness can be characterized by two main components: arousal and awareness (Laureys, Faymonville, & Maquet, 2002a; Posner, Saper, Schiff, & Plum, 2007). Clinically, arousal is manifested by spontaneous eye opening, whereas awareness is assessed by responses to external stimuli (e.g., command-following, visual pursuit, adequate emotional response). Although loss of arousal is associated with altered awareness (e.g., sleep, anesthesia), preserved arousal level does not necessarily imply preserved awareness. Following severe brain damage, a patient can either die (brain death) or evolve through different states of altered consciousness before possibly recovering full consciousness. Each of these states is associated with more or less severe cognitive and motor disabilities (see Figure 1.1). As shown in Figure 1.1, the restoration of spontaneous or elicited eye opening, in the absence of voluntary motor activity, marks the transition from coma to vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (VS/UWS). The passage from VS/UWS to the minimally conscious state minus (MCS–) is marked by the appearance of non-linguistic signs of conscious awareness. MCS plus (MCS+) patients show clear evidence of receptive or expressive language function. Emergence from MCS is signaled by the return of functional communication or object use. The locked-in syndrome (LIS) is the extreme example of intact cognition with nearly complete or complete motor deficit (Laureys, Perrin, Schnakers, Boly, & Majerus, 2005b). Each of these states has also been studied in terms of brain metabolism at rest or brain activation in response to external stimuli.

Brain death

The term “brain death” suggests that the organism cannot function as a whole. Critical functions such as respiration, blood pressure, neuroendocrine and homeostatic regulation, and consciousness are permanently lacking. The patient is apneic and unreactive to environmental stimulation (Guidelines for the determination of death, 1981). This term can only be used after bedside demonstration of irreversible cessation of functions of the brain and the brainstem. Brain death is usually caused by a severe brain lesion (e.g., massive traumatic injury, intracranial hemorrhage, or anoxia) resulting in an intracranial pressure higher than the mean arterial blood pressure. The diagnosis can be made within 6–24 hours, after excluding pharmacological or toxic treatments or hypothermia as potential confounders. This state is characterized by the absence of residual brain metabolism, confirming the absence of neuronal function in the whole brain (Laureys, Owen, & Schiff, 2004a).

Coma

Some patients can remain in a coma, neither aroused nor aware, for several weeks. Their eyes are constantly closed and they do not manifest voluntary behavioral responses. Generally, patients emerge from their comatose state within two to four weeks (Posner et al., 2007). The prognosis is influenced by different factors such as etiology, the patient’s general medical condition, and age. Outcome is most likely to be bad if, after three days of observation, there are still no pupillary or corneal reflexes, there is stereotyped or no motor responses to noxious stimulation, and an isoelectrical or burst-suppression electrophysiological (EEG) pattern is observed. Prognosis in traumatic coma survivors is better than in anoxic cases (Whyte et al., 2009). Recovery from coma may lead to a vegetative state, a minimally conscious state or, more rarely, to a locked-in syndrome (Bruno, Vanhaudenhuyse, Thibaut, Moonen, & Laureys, 2011; Posner et al., 2007). Coma is generally associated with a global decrease in brain metabolism of 50–70% of the normal range.

Vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome

The “vegetative state” (VS), “an organic body capable of growth and development but devoid of sensation and thought,” was defined in 1972 by Jennett and Plum (Jennett & Plum, 1972). The term was proposed to describe a state in which autonomic functions (e.g., cardio-vascular regulation, thermoregulation) and arousal (wakefulness and rest cycles) were preserved with the absence of awareness. Behaviorally, patients in VS open their eyes spontaneously or in response to stimulation, but they only show reflexive (involuntary) responses to the environment. Recently, some have suggested replacing the term VS with “unresponsive wakefulness syndrome” (UWS) in order to avoid the negative association with the word “vegetative” and to better describe the behavioral pattern observed in this population (Laureys et al., 2010). It has been suggested that the state can be defined as permanent when there is no recovery after a specified period (three or twelve months, depending on etiology, anoxic or traumatic, respectively) (American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, 1995; Jennett, 2005). However, further evidence suggests that patients in a VS/UWS can recover even after this length of time, so the term may therefore not be appropriate (Estraneo et al., 2013; Estraneo, Moretta, Loreto, Santoro, & Trojano, 2014). Studies on global brain metabolism have usually shown a decrease of about 40–50% of normal range values in VS/UWS patients (Stender et al., 2015), although some studies have reported cerebral metabolism (Schiff et al., 2002) or blood flow (Agardh, Rosen, & Ryding, 1983) in the normal range in some cases.

Minimally conscious state

Patients in a minimally conscious state (MCS) are aroused and manifest fluctuating but consistent and reproducible signs of awareness (Giacino et al., 2002). Visual pursuit appears to be an early behavioral marker of the transition from VS/UWS to MCS (Giacino & Whyte, 2005), but these patients can also show other voluntary behavioral responses and/or oriented emotional reactions such as responses to verbal orders, object manipulation, oriented responses to noxious stimulation, visual fixation, or appropriate crying/smiling. However, responsiveness can fluctuate, which makes the detection of voluntary behaviors at the bedside challenging. Some researchers have recently proposed subcategorizing MCS into MCS minus (MCS–) and MCS plus (MCS+), based on evidence of differences in brain metabolism within the language network (Bruno et al., 2012; Bruno et al., 2011). MCS+ would encompass patients who show clear evidence of receptive or expressive language function (e.g., command-following). In contrast, MCS– would define those who demonstrate only nonlinguistic signs of conscious awareness (e.g., visual pursuit). The specific behaviors required to meet the criteria for MCS+ and MCS– are still being discussed and additional empirical investigation is needed before these categories can be implemented in clinical practice.

Emergence from MCS is defined by the recovery of functional communication and/or functional use of objects (Giacino et al., 2002). Some patients can remain in MCS without fully recovering consciousness for a prolonged period (Fins, Schiff, & Foley, 2007). Prognosis for recovery in MCS patients remains very difficult because of the marked heterogeneity in the underlying pathophysiology of these patients. However, a better outcome for MCS as compared to VS/UWS patients has been reported (Lammi, Smith, Tate, & Taylor, 2005; Luauté et al., 2010). If the global metabolic rate remains usually higher in MCS than in VS/UWS (Stender et al., 2015), it does not always show substantial changes and return to normal after recovery of consciousness (Laureys, Lemaire, Maquet, Phillips, & Franck, 1999). However, activation studies reported differences between MCS and VS/UWS patients, suggesting a disparity between cognitive preservation and processing of external stimuli such as pain (see also Chapter 2 and 3).

Locked-in syndrome

Not to be misidentified as patients suffering from an altered state of consciousness, locked-in (LIS) patients cannot move or talk but they are usually able to use vertical eye movements and/or blink to communicate. This syndrome is often due to a selective supranuclear motor deefferentation that results in the paralysis of all four limbs and the last cranial nerves without interfering with consciousness (American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, 1995; Plum & Posner, 1983) or cognition (Schnakers et al., 2008b). Therefore, these patients may present the same behavioral pattern as that observed in VS/UWS or MCS patients, which often leads to misdiagnosis of altered state of consciousness (see also Chapter 8). LIS can be subcategorized based on the extent of motor impairment (Bauer, Gerstenbrand, & R...