![]()

1

COGNITIVE PROFILES IN ADULTS AND CHILDREN WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA AND HOW THEY HAVE INFORMED US IN DEVELOPING CRT FOR ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Kate Tchanturia and Katie Lang

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious mental health disorder, with an enduring and chronic course, as well as high morbidity rates (Arcelus et al. 2011). In present times there is little in the way of effective treatments, and the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE 2004) currently does not have a first line (best) recommended treatment for adult anorexia nervosa patients. It is therefore important for us to focus our attention on underlying cognitive traits that may be present in individuals with anorexia, and which may make engaging in conventional psychological therapies difficult.

To be beneficial, many talking therapies such as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Cognitive Analytical Therapy (CAT) require the individual to engage in complex cognitive processes. CBT, for example, is based on the principle of making behavioural changes, and learning more adaptive behaviours in order to affect cognitive processes. If, however, someone’s cognitive style makes it difficult for them to think flexibly and biases them to focus on detail rather than in a gistful way, they are likely to find this process incredibly difficult. Therefore, whether or not an individual will find psychological treatments such as CBT helpful will largely depend on factors such as IQ and neurocognitive style. We use CBT here as an example, but it largely applies to any kind of therapy, because psychological (talking) therapies are based on the premise that patients can learn to replace maladaptive behaviours with more adaptive ones.

Recent research has highlighted a particular neuropsychological profile in AN, in which certain inefficiencies in cognitive processing have been observed. In particular, such inefficiencies have been identified in the areas of set-shifting and central coherence (e.g. for more details our published work, Tchanturia et al. 2011, 2012; Lang et al. 2014a; Roberts et al. 2007; Lopez et al. 2008a,b). Set-shifting refers to the ability to move flexibly from one behaviour or mental set to another and adapting to a changing and unpredictable environment (Lezak 2008). In everyday behaviour, set-shifting is expressed in flexibility of thinking. Another important cognitive feature in the literature associated with anorexia is extreme attention to detail versus bigger picture thinking; many researchers refer to this as central coherence. Central coherence is the ability to contextualize information and integrate it into the ‘bigger picture’ (Frith 1991). With an extremely focused rigid and detailed processing style, it is understandable why individuals with anorexia might find conventional psychological treatments difficult. The idea of such cognitive traits acting as maintaining mechanisms was proposed by Schmidt and Treasure (2006), who suggested that these cognitive styles might be one of the four main factors maintaining anorexia.

This chapter shall therefore focus on set-shifting and central coherence and review the evidence for the cognitive profile of adults and children with anorexia.

Set-shifting

Outside of the eating disorders field, flexibility has been implicated as a strong predictor of response to psychological treatment in a range of mental health disorders, as well as being beneficial for general health and wellbeing (Kashdan and Rottenburg 2010).

Within the sphere of anorexia, many patients report anecdotally that they find problem-solving challenging, due to their inflexible or rigid thinking style. This is coupled with our clinical observations that a majority of patients with anorexia find it difficult to accept the idea of recovery (particularly when very underweight and nutritionally compromised), or to change their behaviours not only around eating but also everyday routines.

Such observations have sparked an interest into mental flexibility, and about a decade ago our attention became focused on research into flexibility of thinking in the adult population in people with anorexia (e.g. Tchanturia et al. 2001, 2002, 2004a,b, 2011, 2012).

Neuropsychological tasks assessing mental flexibility have been used to examine set-shifting and test our clinical observations. Table 1.1 lists the most common of these tasks.

The findings from our early experimental studies (e.g. Tchanturia et al. 2004a,b) matched our clinical observations, and confirmed that due to their more inflexible thinking styles, people with anorexia found cognitive flexibility tasks particularly challenging compared to those without eating disorders. We have continued this line of research for more than a decade now, and as experts within the field, we are convinced that this inflexible thinking pattern is present not only in patients currently ill with anorexia but also in individuals who have recovered from the disorder, in comparison to non-eating-disorder groups. It is still not clear whether this is the case for patients with bulimia and other eating disorders (Tchanturia et al. 2012, 2011; Roberts et al. 2013, 2007; Harrison et al. 2012; Van den Eynde et al. 2011).

The best and most robust way of examining the experimental evidence is through study replication and critical appraisal of the literature. Two decades ago it was impossible to understand neurocognitive profiles in eating disorders for two main reasons: Firstly, the number of studies was extremely limited. Our first attempt in 1999 to critically appraise the eating disorders literature in neuropsychology was unsuccessful, due to the twelve existing studies’ variability in methodology, leading to unclear findings. Such studies concluded that neuropsychological functioning was ‘intact’, even in the starved phase of anorexia. Secondly, studies were looking at general executive functions and not using a hypothesis-driven approach to guide their investigations. This meant that these studies were not focusing on the most clinically relevant aspects of cognition, namely set-shifting and central coherence.

TABLE 1.1 Description of popular experimental set-shifting tasks

| Name of task | Description |

Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST, Heaton et al. 1993) | Originally this test was developed using cards, but it is now computerised to minimise experimenter bias/error and to save time. Participants are presented with a stimulus card and required to match it to one of four category cards (1 red triangle, 2 green stars, 3 yellow crosses or 4 blue circles). The correct way to sort the cards is unknown and the participant must use feedback on whether they have sorted correctly, to guide their next move. The sorting rule changes unpredictably and the participants must adapt to the rule change. The number of perseverative errors is used as a measure of set-shifting. The largest dataset on WCST in eating disorders is published in an open access journal (Tchanturia et al. 2012) and can be found at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3257222/ |

Trail Making Task (TMT, Delis et al. 2001) | Originally developed as pen and paper task, there are now computerised versions available (it is sub-test of D-KEFS test battery). TMT consists of two parts: In Part A, participants are required to connect twenty-five numbered dots in numerical fashion as quickly and accurately as possible. In Part B, participants are asked to connect the dots, but this time alternating between numbers and letters (e.g. 1-A-2-B etc.). A measure of set-shifting ability is taken from the amount of time taken to complete Part B. |

The Brixton (Burgess and Shallice 1997) | A blue dot is displayed either on pages, or in the computerised version on a screen, and moves around in a sequence. Participants are asked to predict the next position where it will appear. The sequence changes unpredictably and participants need to adapt to the new sequence in order to guess its next position correctly. |

| The largest dataset published to the data in eating disorders can be found in an open access journal (Tchanturia et al. 2011) at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3115939/ |

Hypothesis-driven research started in 2000 and now there are many adult population-based studies from different parts of the world confirming our original experimental findings, that cognitive flexibility is problematic for people who are in the actively ill state of anorexia. Studies are available from various groups from Italy (Tenconi et al. 2010; Abbate Daga et al. 2012); Germany (Fredrick et al. 2011, 2013); USA (Steinglass et al. 2006) and the Netherlands (Danner et al. 2012) to name but a few.

Data analysis

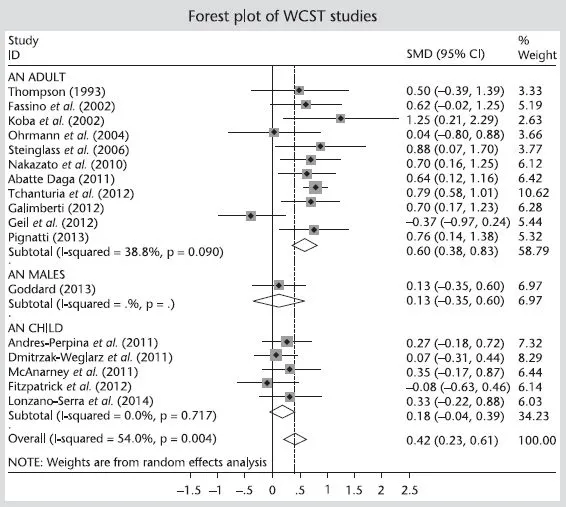

The best way to visually show the results of a meta-analysis (combining results from multiple studies) is by using forest plots, whereby all of the evidence is put together in one graph. Effect sizes (a standardised way – usually Cohens d – of measuring the difference between two groups) are displayed on the x axis with each individual study plotted on the y axis. In regard to measurements, 0.30 and under is seen to be a small effect size, 0.30–0.50 a medium effect size and 0.50 or more is a large effect size. The effect size for each individual study can be seen, with an overall sum of effect sizes displayed on the bottom.

Figure 1.1 displays a forest plot of the available anorexia nervosa (AN) WCST studies. The top half of the forest plot depicts adult AN WCST studies. The graph shows that across the various studies, adults with anorexia made more perseverative errors (as the studies sit to the right of the line), with an overall effect size of 0.60 (large effect size). This means that they found it difficult to switch to new rules – dropping redundant rules and strategies and adapting to the changing environment – when the conditions of the task changed. Instead they tended to continue to follow the old rule, thus exhibiting perseverative errors. It should also be highlighted here that Goddard et al. (2013) has been separated from the other adult studies as this study only contained male AN patients.

FIGURE 1.1 Forest plot of WCST studies: adults with AN (top half) and children with AN (bottom half)

The evidence based on the research in the adult population with anorexia clearly shows (with the exception of one study, Geil et al. 2012) that patient groups are performing less efficiently than controls on set-shifting tasks.

More recently the attention of the field has turned to examine the neuropsychological profile of children and adolescents with anorexia. This interest has been spurred on by the hypothesis that inefficient set-shifting may be an endophenotype for the disorder. An endophenotype is a measurable biological, behavioural or cognitive marker which is present more often in individuals with a disorder than in the general population (Gottesman and Gould 2003).

Endophenotypes must fulfil four criteria:

1 They must be associated with a certain population (e.g. anorexia)

2 They must be present regardless of whether or not the illness is in the acute phase or recovered stage (i.e. not state-dependant)

3 They must be heritable, and

4 Must also be present to a higher degree in non-affected family members, such as siblings or parents (Gottesman and Gould 2003).

As well as evidence of inefficient set-shifting in individuals currently ill with anorexia, the trait has also been observed following recovery and also in unaffected sisters of those with anorexia (Roberts et al. 2010), providing support for the endophenotype hypothesis. However, a recent meta-analysis of the child and adolescent set-shifting data in anorexia did not reveal a clear difference in performance on set-shifting tasks between children with and without anorexia (Lang et al. 2013). A forest plot displaying studies using the WCST with children with AN can be also be found in Figure 1.1 (bottom half).

As can be seen from this graph, the overall sum of effect sizes from the ch...