- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Christianity: The Basics

About this book

Christianity: The Basics is a compelling introduction to both the central pillars of the Christian faith and the rich and varied history of this most global of global religions. This book traces the development of Christianity through an exploration of some of the key beliefs, practices and emotions which have been recurrent symbols through the centuries:

- Christ, the kingdom of heaven and sin

- Baptism, Eucharist and prayer

- Joy, divine union and self denial

Encompassing the major epochs of Christian history and examining the unity and divisions created by these symbols, Christianity: The Basics is both a concise and comprehensive introduction to the Christian tradition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE BASICS OF JESUS

THE ORIGINS OF CHRISTIANITY IN THE FIRST CENTURY

When Jesus was born, probably in 2 CE, the Temple in Jerusalem constituted the ritual center of Judaism. Jews came from all over the known world to offer sacrifice according to the Torah, the Law of Moses as written in the first five books of the Scriptures of Israel.

THE COMMONLY ACCEPTED SYSTEM OF DATING

In 525 CE, a monk and scholar named Dionysius Exiguus established an historical chronology, taking Jesus’ birth as the first “Year of the Lord” (Anno Domini, or “AD”). The system is still in use, with “BC” (“Before Christ”) marking time prior to Jesus’ birth. Today scholars commonly refer to dates as either “Before the Common Era” (BCE) or “Common Era” (CE). In setting out dates for events, Dionysius had to synchronize calendars from various regional governors and kingdoms, each with its own reckoning of dates. There had been no coordinated timeline, but schemes that followed the years of one reign or another, with differing views of when a new year even began. The timing he assigned has therefore been subject to correction as further data has been brought to bear and organized.

Herod the Great, who ruled as the client-king of Rome, had physically expanded the Temple, which stood on a stone plinth of some thirty-five acres that is still extant. The Herodian edifice is known as the Second Temple, since the First Temple, built by Solomon, had been destroyed in 586 BCE. The largest structure of its kind at the time, the Second Temple needed to be huge to accommodate the offerings of all Israel. According to the Torah only that one place on earth was acceptable to the God of Israel for the purpose of sacrifice.

Alongside this clear ritual center, the Torah guided the ethical behavior of Israelites. The Torah concerns not only basic moral instruction, but also commandments in regard to what foods should be eaten and other rules of purity. Sacrifice demanded that Israelites and their offerings be in a pure condition as they approached the God of Israel.

In addition to the written Torah, a group called the Pharisees held that oral Torah, teachings that they committed to memory, also needed to be followed. The oral Torah derived from Moses alongside the Scriptures in their view, but could only be accessed through the teachings of the Pharisees themselves. Because they held to additional regulations as necessary to make an Israelite pure, they came to be called “Separatists,” the probable meaning of the term “Pharisee” in Hebrew. Inside the Temple itself, however, control of proceedings was in the hands of an hereditary priesthood among privileged families, allegedly derived from a priest named Zadok (and hence called the Sadducees in the Greek Gospels). They adhered to the written Torah alone.

TORAH OR LAW

Torah means “guidance” in Hebrew and refers to the revelation given to Moses in the period between the exodus and Israelite settlement in the land of Canaan. Rendered “law” (nomos) in Greek, the Torah addressed common behavior, the regulation of sacrifice, and the maintenance of that standard of purity that was expected of Israel as a sacrificial community. Alongside the written Torah (the biblical books called Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), the Pharisees held that their oral traditions also reached back to Moses. Eventually, these oral traditions were written down also, in the work called the Mishnah (c. 200 CE).

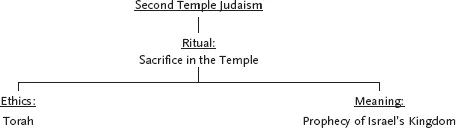

As long as the Second Temple stood, Judaism during the first century adhered to the view that correct sacrifice there, together with adherence to the Law, would bring about the fulfillment of the promise to Abraham, the forefather of all Israel. Once settled in the Promised Land, God had assured Abraham that “all the families of the earth” would find their blessing in the Israelites (Genesis 12:3). This prophecy of future, virtually limitless expansion—an Israelite kingdom greater than any power on earth, reaching from the Nile to the Euphrates (Genesis 15:18)—fills out the religious system of Judaism during the Second Temple period. A clear goal and meaning animated a system of precise ritual and ethical commitment.

As a religious system, Judaism of this Second Temple period allowed great diversity in culture and yet unified Jews, most of whom by this time lived in what is called the Diaspora. Although the word literally means “dispersion” in Greek, by the first century Israelites occupied a vital and proud place among the civilized peoples from Babylon to Spain. Over the previous centuries Jewish emigration had been largely voluntary, although policies of deportation also played their part. For all the differences among Jews scattered around the Mediterranean world—in language, local custom, and even how to define Scripture—the ritual of the Temple, the Torah of Moses, and the promise of the Prophets gave them a common identity.

JESUS’ FIRST REVOLUTION

Jesus was a revolutionary, but not because he headed up an insurrection. Nor did he set out deliberately to found a new religion. Yet the way he put the Judaism of his time into practice changed the religious system. That alteration affected the whole, and within only a few decades, a different religion emerged. All his basics were Jewish, but by means of two revolutions, Jesus arranged them into a new system.

One of the earliest sources within the Gospels is called “Q,” an abbreviation of the German word Quelle, which means “source.” Jesus’ teaching was arranged in the form of a mishnah (a compilation of a rabbi’s teaching by his disciples). This mishnah was preserved orally in Aramaic, Jesus’ original language, and in a classic passage (Luke 10:1–12) it explained how his followers should act on his behalf. He sends them out as his personal representatives. The term used for “agent” in Greek (apostolos) comes into English as “apostle,” the highest human authority, Jesus’ envoy. As he delegates his followers, he explains his goals in the clearest possible way. Jesus’ commission to them reflects the program of activity he embraced for himself and expected the apostles to follow.

Jesus instructs these disciples to travel without provisions. That seems strange, unless the image of the harvest at the beginning of the charge (Luke 10:2) is taken seriously. Because they are going out as to rich fields, they do not require what would normally be needed on a journey: purse, bag, and even sandals are all dispensed with (Luke 10:4). They should treat Israel as a field in which one works, not as an itinerary of travel. The support they receive as they make their way around Israel will be the sign whether their message is accepted or not.

Another powerful comparison is at work within this commission alongside its image of Israel as a land ready for harvest. Pilgrims who entered the Temple in Jerusalem also did so without the bags and staffs and purses that they had traveled with. All such items were to be deposited before worship, so that one was present without encumbrance, just as an Israelite. Part of worship was that one was to appear in one’s simple purity, and that imperative was incorporated into the apostles’ work.

By his program of constant travel within Israel, Jesus treated the whole of the land as holy, and he instructed his disciples to do the same—dispensing with the equipment of travel. He accepted hospitality in every place that he entered and even acquired the reputation of a “glutton and a drunkard,” “a friend of sinners” (see Matthew 11:19 and Luke 7:34). For him any person who joined in eating with other Israelites, both forgiving and being forgiven for that purpose and acknowledging that God was the true host of the occasion, belonged in his fellowship. The apostles define and create the true Israel to which they are sent, and they tread that territory as on holy ground, shoeless and without staff or purse.

The meaning behind this activity on behalf of extending purity into Israel is grounded in Jesus’ characteristic prayer, known as the Lord’s Prayer or the Paternoster. The New Testament includes two versions of the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9–13; Luke 11:2–4), both of which derive from the source known as “Q.” Luke’s is widely considered the earlier in form, and it does seem plain that Matthew presents what is, in effect, a commentary woven together with the prayer. The relative sparseness of Luke has won it recognition among scholars as the nearest to the form of an outline which Jesus recommended to his followers.

Matthew | Luke |

Our father, who is in the heavens, | Father, |

your name will be sanctified, | your name will be sanctified, |

your kingdom will come, your will happen as in heaven, even on earth. | your kingdom will come. |

Our bread that is coming, give us today, | Our bread that is coming, be giving us each day, |

and release us our debts, as we also have released our debtors, | and release us our sins, because we also ourselves release everyone who is indebted us, |

And do not bring us to the test, but deliver us from the evil one. | And do not bring us to the test. |

One Gospel cannot be explained on the basis of literal copying from another Gospel. Matthew reflects the use of the prayer in a congregation of believers, while Luke is geared more for private use. In the renderings of the Greek texts above, indented material is widely considered to be commentary that helped explain the prayer.

A model is at issue in Jesus’ teaching, rather than a precise repetition of words. (Jesus warned against mechanical or wordy prayer, Matthew 6:7.) The basic model of the Lord’s Prayer consists of calling God father, rejoicing that his name shall be sanctified and that his kingdom shall come, and then asking for daily bread, forgiveness, and not to be brought to the test.

The model unfolds under two major headings:

I) | an address of God (1) as father, (2) with sanctification of God’s name, and (3) vigorous assent to the coming of God’s kingdom; |

II) | a petition for (1) bread, (2) forgiveness, and (3) constancy. |

Assessed by its individual elements, the Lord’s Prayer may be characterized as a fairly typical instance of Judaic practice in its period. In particular, Jesus reflects the oral, memorized culture of Jewish Galilee, where the Psalms were known by heart and used in the course of worship. To call God “father” was—in itself—not unusual. Psalm 103:13 associates God’s fatherly care with his actual provision for prayerful Israel: “As a father has compassion upon his children, so does the LORD have compassion upon those who fear him.”

The same Psalm (103:1) shows that the connection of God’s “holy name” to his fatherhood was seen as natural. Sanctifying God’s name acknowledges that holiness, and the earliest of Rabbinic texts of prayer—such as the Kaddish, which means “Sanctified [be God’s name]”—insist on that recognition. That God’s holiness is consistent with people being forgiven and accepted by him is the foundational motif of Psalm 103, where the singer calls on his own soul to bless the LORD “who pardons all you iniquities and heals all your diseases” (Psalm 103:3). Finally, this psalm portrays God as the hand that guides creation and revelation, so in nature as well as in the justice that emerges in human society, “his Kingdom rules over all” (Psalm 103:19).

The initial point of Jesus’ model of prayer is that God is to be approached as father, his name sanctified, and his Kingdom welcomed. The act of prayer along those lines, with great variety over time and from place to place and tradition to tradition, has been a hallmark of Christianity.

To address God as one’s father, and then to sanctify his name, acknowledges ambivalence in the human attitude toward God. He approaches us freely and without restraint, and yet is unapproachable, as holy as we are ordinary. The welcoming of his Kingdom, of his comprehensive rule of justice within the moral ambiguities of this world, wills away this ambivalence. God’s intimate holiness is to invade the ordinary, so that any sense of estrangement is overcome.

The three elements which open the prayer characterize a relationship and an attitude toward God which the one who prays makes his own or her own. The distinctiveness of the prayer is nothing other than that consciousness of God that Jesus enjoyed. Awareness of God and of oneself is what Christians kindle when they pray the Lord’s Prayer. And at the same time, the prayer is nothing other than the Lord’s; whatever the power of such a consciousness, it is only ours because it was Christ’s first. That is why the consciousness of praying in this manner produces relationship: one is God’s child and Jesus’ sister or brother in the same instant.

In this case, as in others, a basic of Christianity first emerged in Aramaic, the language of Jesus and his earliest followers. A Semitic tongue similar to Hebrew, it is nonetheless a different language; that is why the Hebrew Bible had to be translated into Aramaic during the time of Jesus. (The result is called targum, a term that means “translation” in Aramaic.) But the Gospels and all the other books in the New Testament were composed in Greek. They are based in a large proportion upon Aramaic sources, but their writing is firmly located in the “common” Greek dialect (the Koine) of the first century. Yet the elements of the Lord’s Prayer are clearly drawn from the Judaic tradition, and Aramaic wording can be identified as the source of the Greek texts of Matthew and Luke:

‘abba | father/source |

yitqadash shemakh | your name will be sanctified |

tetey malkhutakh | your kingdom will come |

hav li yoma lakhma d’ateh | give me today the bread that is coming |

ushebaq li yat chobati | and release me my debts |

ve’al ta‘eleyni lenisyona | not bring me to the test |

Although the individual parts of the whole are common, Jesus assembled them in a way that produced a shift in the religious system of Judaism. Prophecy of the coming Kingdom had been the meaning behind both ritual and ethics, but in Jesus’ practice, the true meaning of all human activity—and the opening of the prayer—was instead the relationship to God as Father. That becomes forever the determinative focus among the disciples of Jesus.

The Kingdom remains vital, but in a new way. Instead of its being the aim and meaning of ritual and ethics, Jesus prays for the prophetic Kingdom within human experience, as Matthew explains it, “on earth as in heaven.” Prophecy of God’s Kingdom, rather than the Kingdom of Israel, is now a principle of ethics, of people acting in such a way that God is known as Father. That is why Jesus tells parables of God as a King that also conve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Timeline

- 1 The basics of Jesus

- 2 Catholic, Orthodox basics

- 3 Basics in the Middle Ages

- 4 Reformation and Enlightenment basics

- 5 The basics of modern Christianity

- Postludes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Christianity: The Basics by Bruce Chilton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.