This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Routledge Course in Translation Annotation: Arabic-English-Arabic is a key coursebook for students and practitioners of translation studies.

Focusing on one of the most prominent developments in translation studies, annotation for translation purposes, it provides the reader with the theoretical framework for annotating their own, or commenting on others', translations.

The book:

-

- presents a systematic and thorough explanation of translation strategies, supported throughout by bi-directional examples from and into English

-

- features authentic materials taken from a wide range of sources, including literary, journalistic, religious, legal, technical and commercial texts

-

- brings the theory and practice of translation annotation together in an informed and comprehensive way

-

- includes practical exercises at the end of each chapter to consolidate learning and allow the reader to put the theory into practice

-

- culminates with a long annotated literary text, allowing the reader to have a clear vision on how to apply the theoretical elements in a cohesive way

The Routledge Course in Translation Annotation is an essential text for both undergraduate and postgraduate students of Arabic-English translation and of translation studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Routledge Course in Translation Annotation by Ali Almanna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Annotation – defining matters

In this chapter …

In this chapter, an attempt is made to reach a precise definition of the term ‘annotation’ focusing on the various processes and stages of the annotating mechanisms and such related terms as ‘commenting’, ‘assessing’, ‘revising’, ‘editing’, ‘proofreading’ and so forth on the one hand and placing the terms concerned in their right place according to Holmes’s map. Further, another attempt will be made to show that annotation, like other translation activities, is characterized by subjectivity. The question that will be implicitly addressed in this chapter is: Can subjectivity be kept to a minimum?

Key issues

- Annotation

- Assessment

- Comment

- Criticism

- Evaluation

- Reviewing

- Revision

- Subjectivity

- Textual profile

Place of annotation and related issues

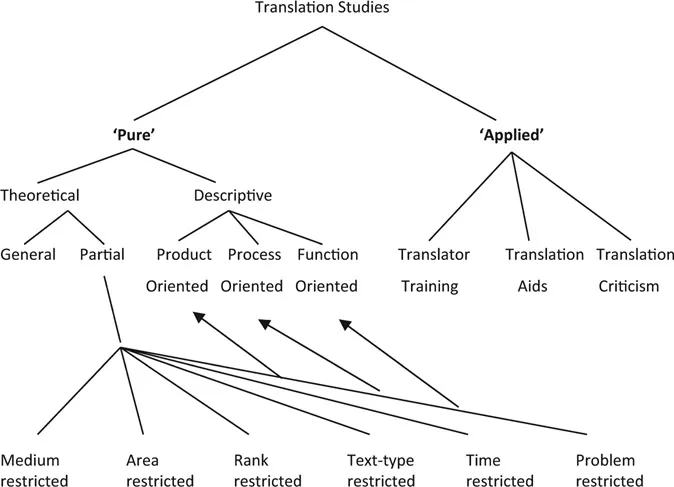

The whole discipline is divided into two main branches, viz. ‘pure translation studies’ and ‘applied translation studies’ (Holmes 1970/2004: 172–185; also discussed in Toury 1995; Baker and Malmkjær 1998; Munday 2001/2008/2012; Hatim 2001; Hatim and Munday 2004; Chakhachiro 2005 among others). The former deals with theoretical and descriptive studies, whereas the latter focuses on issues, such as translator training, translator aids and translation criticism. The figure above, received later from Gideon Toury (1995: 10), clearly shows these categories.

Holmes’s basic map of translation studies (Toury 1995: 10)

As the central focus of this study is on annotation, comment and other related issues, such as reviewing, assessment, evaluation and so on, attention is intentionally centred on applied translation studies, in particular translation criticism in the sense Holmes (1970/2004: 181–183) uses the term. As far as translation criticism is concerned, it is further subdivided by Holmes into revision, evaluation and reviews of translation. What is of greater importance, here, is that translation criticism (be it revision, evaluation or review) is retrospective in nature, and so are annotation and comment our main concern in the current study. Translation criticism utilizes principles of contrastive analysis, yet it is not aimed at studying differences between two languages. Rather, it focuses on equivalence or ‘matches’ and ‘mismatches’ between the source text (ST) and target text (TT). In spite of using similar principles and concerning themselves with the relationship between the ST and TT, the use of revision is concerned with the ‘whys’, whereas translation criticism concentrates on the ‘whats’ and ‘ho ws’ (Chakhachiro 2005: 227–228).

Building on the premise that translation criticism is conducted retrospectively, one cannot avoid adopting parameters that may be considered mainly subjective when conducting annotation, comment or comparative analysis (cf. Lauscher 2 000; Reiss 2000; House 2001; Chakhachiro 2005). However, the reviewers’ comments and translators’ annotations need to be systematic in order to control their own subjectivity and achieve consensus about an outcome.

Annotation is different from revision, reviewing, proofreading, editing, assessment or evaluation in the sense that annotation is conducted by the translator him/herself while facing a particular problem. The purpose of annotation is to defend the choices made by the translator; hence the importance of sensitizing trainee translators to the existence of such controversial issues and the local strategies that may be invoked to accommodate them. In the main body of the translation, the ST and TT can appear on facing pages, with notes at the bottom of the page (footnotes) or at the end (endnotes), but they do not have to. It seems likely that the majority of the notes will be on the translation side (be they on translation strategies, language role, aspects of pragmatics, aspects of textuality, cultural aspects, stylistic aspects or semiotic aspects; see next chapters in this book). However, the original text may be annotated also, especially with regard to grammatical difficulties or ambiguities.

When the text has already been translated, especially if it has been translated more than once, the annotations may also provide examples of the other translated versions. It is entirely appropriate to refer to translation theories where this provides a clue to the justification of a certain approach. An annotated translation should have a brief introduction presenting the text, indicating its interest and explaining what kinds of difficulties it might present. Getting this introduction just right is important: A short background to the original text and its author needs to be given by the translator prior to embarking on the actual act of annotating. Further, when the ST is in any way uncertain, an explanation needs to be provided of which text has been used or how it was determined. This applies particularly to older texts but not exclusively so. The introduction might well address the problem of what a translation is, dealing with some theoretical points and suggesting particular problems inherent in translating between the two languages concerned or dealing with the text type (for more details, see next chapter).

Annotation and related issues

Linguistically speaking, annotation derives from the verb ‘annotate’, which means to add explanatory notes, supply a work with critical commentary or explanatory notes or provide interlinear explanations for words or phrases. Its synonyms include ‘comment’ (cf. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English 1987/1995: 33). However, in this study, a distinction is made between the term ‘annotation’ and its synonym ‘comment’. While ‘comment’ is used when commenting on others’ translations, ‘annotation’ is used to refer to the critical notes offered by translators on their own translations. Further, annotation should not be confused with a translation with a lot of footnotes and/or endnotes. As such, annotation can be envisaged as a reflection. To sum up, annotation for translation purposes is used to explain the decisions taken by the translator. Obviously, therefore, they should not be used sparingly in this case, as the absence of a note might be taken as indicating that a difficulty or obscurity had not been properly understood.

When doing translation-oriented analysis in order to annotate one’s own translation or comment on somebody’s translation, one needs to distinguish between obligatory features and optional features. Obligatory features involve choices that must be followed by the translator in order to satisfy the rules imposed by the target language (TL) system, without which the translation will be ungrammatical. However, optional features represent cases in which the translator can exercise real choice by deciding on one translation option rather than another/others. Annotation is needed by translators when translating a segment that leaves them with more than one option to follow. In this case, the translator starts a series of actions, including analyzing the ST, highlighting the elements that need to be reflected in the TT and prioritizing among the competing elements. Hence the need for annotation to persuade their readers that they are aware of other options but opted for this particular local strategy or a combination of many local strategies in rendering the text at hand for a particular reason. Annotation is a common method of reflection.

With regard to revision, scholars’ views on revision can be reduced to two main perspectives:

- the revision should be conducted by a person other than the translator (cf. Dickins et al. 2 002; Samuelsson-Brown 2 004; Chakhachiro 2005; British Standards Institution; Mossop 2007a, 20 07b; Robert 2008 among others) and

- the revision should be conducted by the translator him/herself (cf. Sedon-Strutt 1990; Sager 1 994; Yi-yi Shih 2 006; Mossop 2007a among others).

Building on the assumption that everybody agrees a translator has to check his/her own work before submitting it to a client and/or translation project manager, this binary subdivision is rather fake and ambiguous.

As for identifying the persona of the reviser, it is strictly connected to identifying the moment in time at which the revision process has to be carried out; in other words ‘who’ is the reviser also depends and is interrelated with the discussion on at ‘which level’ of the translation process revision is expected to take place. According to the BSEN15038:2006 stand ard (British Standards Institution 2006: 11), revising translation is a compulsory stage in a professional and quality-oriented translation process at its macro level, and it should be conducted by a person other than the translator. Mossop (2007a: 6) speaks of two types of revision: unilingual and comparative revision. When conducting a unilingual revisi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Annotation – defining matters

- 2 Annotation and global strategies

- 3 Annotating translation strategies

- 4 Annotating grammatical issues

- 5 Annotating lexical and phraseological choices

- 6 Annotating aspects of cohesion

- 7 Annotating register

- 8 Annotating pragmatic, semiotic and stylistic aspects

- 9 Annotating cultural and ideological issues

- 10 Annotation into action

- References

- Index