![]()

PART

ONE

BUILDING AN UNDERSTANDING OF DESIGN FOR THE INTERESTS OF THE PUBLIC

![]()

Chapter 1

Creation of a Paradigm

The emergence of the socially aware design curriculum and its historical impact on architecture and design education in the united states

Introduction

To tread lightly from the beginning seems an injustice to those brave enough to selflessly effect social change through design. For this is a story about perseverance and sacrifice. A perseverance that we will attempt to unravel throughout the pages of this book, but that can only be entirely appreciated by going out into the world and participating in an act of giving back. Along with a sacrifice that can only be felt by swinging hammer to nail, or by cutting a piece of lumber for the third time, or by laying down shingles on a roof in the dead of winter, freezing in the cold air, and watching your fellow classmates do the same. All of this just to finish the final few touches on a house for someone you don’t even know, and probably never will. As I’ve discovered through my own education and the time I’ve spent practicing architecture professionally, this is also a story of creating new methods to educate a student interested in architecture and design – and how the steady emergence of the student of these new methods in the profession has changed design practice for the foreseeable future.

We will unfurl this winding path by looking into the history first, at architectural education and the design studio from its birth in the United States during the nineteenth century to its current state – highlighting various events leading to the creation of the asset-based, community-first design studio and design centers. To bring reality to what all too often becomes a fantasy of star-chitecture, we’ll uncover the various paths that can be taken as an architect – and trust me, not all of those involve design, or even architecture for that matter. The next step is to learn from failure. Whether you have ever failed or not (I’m betting you have), the loss of control that comes with such an experience can be the greatest teacher. Sometimes (even when the act is well intentioned) jumping into the unknown can cause suffering, personal or otherwise. How do we react when we are down on our hands and knees, just hoping someone will help? We find a way, we find a solution. That’s what architects do. Step by step, we will see how to effect social change during the act of learning, with an eye towards building upon selflessness in the future. Because the work of a designer – of an artist – is never quite complete.

A “Clearinghouse for the interchange of Knowledge and Skill”

Just west of Boston, Massachusetts, on the north shore of the Charles River, there are two pillars of secondary education. You’ve probably heard of them. Their history is long and interwoven with the development of the United States, from politics to economics to science and technology. They have produced Nobel laureates, presidents of countries (including, of course, the United States), heroes of numerous wars, and leaders of business and societies all over the world. However, Harvard University cannot lay claim to the first school of architecture within an existing educational institute.

When you’re heading out of the city along Massachusetts Avenue and you drive over the Harvard Bridge into Cambridge, you come upon the second pillar, a bustling and condensed world of activity known as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Along a serene, tree-lined street full of people, automobiles, and transit buses, there is a series of buildings that one by one reveal themselves assuredly – through their monumentality, individuality, and star power. You see both the people and the buildings represent intellectual movements – revolutions of understanding if you will. You can perceive the evolution of the institute in the appearance of these buildings. The Stata Center by Frank Gehry, with its folded geometry twisting and turning your eye this way and that; or Simmons Hall by Stephen Holl, with its strict adherence to rectilinear form, porous facade and just the right splash of color. There are also four buildings by I.M. Pei (an alumnus); a chapel and auditorium by Eero Saarinen; the Baker House by influential Finnish architect Alvar Aalto; and, more recently, an extension to the Media Lab by Fumihiko Maki. Of course, we can’t leave out the Great Dome and the Maclaurin Buildings – designed by William Bosworth in the neo-classical Beaux Arts tradition when MIT moved to its current location in 1916. However, each of these well-known architects owes their education in the arts, in some way, to someone who never saw any of their buildings, let alone knew anything about their idiosyncratic (and famous) design tendencies. In fact, every student of architecture in America owes their education to this man.

His name was William Robert Ware (1832–1915), and he was a professor in the founding years of MIT in the 1860s when it was located in three buildings in the Back Bay area of Boston. In 1865 he was asked by the president and founder of MIT, William Barton Rogers, to formalize architectural education at the institutional level by developing a curriculum based on his years teaching students in his own professional firm. In 1866 he wrote and presented what he entitled An Outline of a Course of Architectural Instruction to do just that. What was adopted by the institution in 1868 was the first organized curriculum for how to train students interested in building science to become professional, practicing architects (MIT 1996). To know why this was so innovative, we must look contemporarily towards the concept of the ‘pupillage,’ a dominating force at the time within the profession of architecture in the United States.

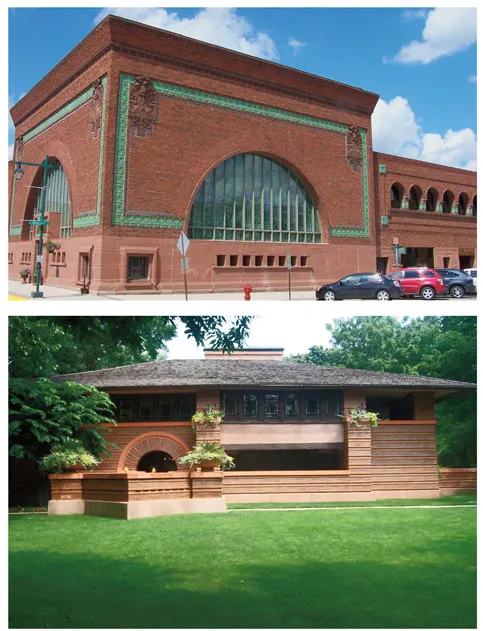

1.1 + 1.2

The National Farmer’s Bank (now Wells Fargo Bank) by Louis Sullivan (1908) in owatonna, minnesota [top] and the Heurtley House by Frank Lloyd Wright (1904) in Oak Park, illinois [bottom].

The structure for architectural apprenticeship (or pupillage) was such that the knowledge of the master architect would be passed down systemically to the pupil in order to preserve the information and to maintain an ordered discipline in architectural expression. However, only when the master architect deemed the pupil ready were they considered so. When looking at historical figures from the nineteenth century, some of the great American architects were trained under this system (near the end of the century, from 1887 to 1893, Frank Lloyd Wright would be taught by Louis Sullivan, for instance) (Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation 2012).

Although this system did a very good job of preparing the pupil for what it would take to be a self-practicing architect, it was not fundamentally a democratic means for the distribution of architectural thought. Early in the second half of the nineteenth century as the embers of the Civil War still smoldered just a few hundred miles to the south (and equally so in the streets of Boston), it was against this backdrop, and amidst various schools of design being created throughout Europe, that William Ware developed his idea to bring architectural education in the United States to the masses. As a private research institute, MIT could still control who would be accepted into the program and who wouldn’t, yet in a democratic manner based on academic merit not patronage. Ware would later go on to create the architecture school at Columbia University in the Bronx, New York, as well. However, it may not be clear up to this point that MIT wasn’t the truly first school of architecture in the United States, so let us take a moment to clarify.

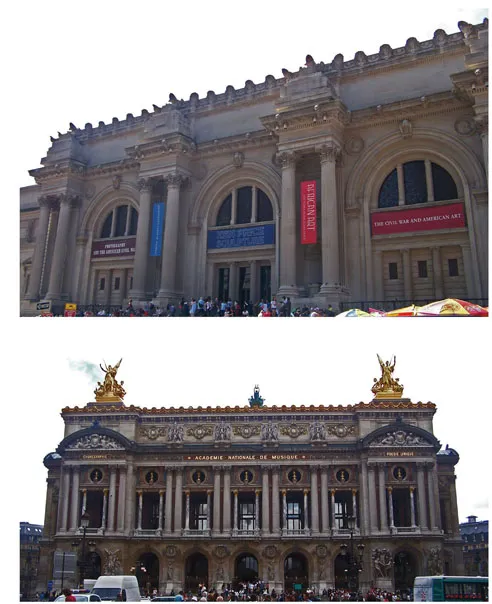

Rare is the person who is entirely self-trained in the technical and design aspects of being a professional architect. There is almost always someone of influence behind each designer. I am no exception, as I can point to three or four individuals who have taught me the values I hold close as a licensed architect. Ware was no exception either. However, his personal influence, his mentor, was a truly pioneering figure in American architectural history. Richard Morris Hunt (1827–1895) was the first American to graduate from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris (McCullough 2011), and when he returned to the United States he would design such projects as the Tribune Building, and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, as well as the Fifth Avenue facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and numerous homes for the wealthy elite in the late nineteenth-century Gilded Age. In addition, Morris assisted in the co-founding of the American Institute of Architects in February 1857 (AIA 2008) and also created the truly first school of architecture – with just four students – at the Tenth Street Studio Building (also designed by Morris) between Fifth and Sixth Avenues in the year 1855 (TFAOI 2007).

1.3 + 1.4

The Fifth Avenue facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1872) by Richard Morris Hunt in New York [top], and L’Opéra de Paris (1875), originally known as the Salle des Capucines and most often referred to as Palais Garnier (after its architect, Charles Garnier) [bottom].

If you ask people who are well versed on architectural history, most point to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts as the beginning of the split from the role of architect-builder into, as Michael Pyatok1 describes, “aestheticians” (Pyatok 2014). A repercussion of this was the loss of input from the master craftsman in the design process. Pyatok continues: “it [the school] was intended to create art, or architecture as an art, independent of utilitarian and engineering purposes” (Pyatok 2014). Instead of using the needs of related crafts to inform the design, the reflection by students and practitioners of architecture was on past empirical styles (Roman, Greek) to symbolically represent the greatness of the French empire during the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. Without the requisite devotion to a monarchy in the United States, however, MIT and Ware established a democratic educational means to achieve certification as an architect within an institution of higher learning. In that act, MIT became the first school of architecture within an institution of higher learning in the United States – a “clearinghouse for the interchange of knowledge and skill” (Ware 1866, 10). The next act would take m...