03 : Introduction

Representing Climates and Regions

Aside from our experience of weather, we only know climate through representations. Understanding the atmosphere as a system has been a scientific and social aspiration for centuries; more recently, since World War II, the precise science of climatology has emerged as a means to investigate, understand, and represent relevant patterns. Within these developments, the geographic region has often been a useful way to make these visual understandings of climate more manageable. Though region is an imprecise term in much of what follows, its function is to identify a geographic condition where the cultural and architectural relationship to climate has some legible consistency.

As we only know climate through representations, architectural representations have increasingly become a crucial means through which to understand existing climatic conditions and also to imagine how to live in the future. Such aspirations enrich the field and also serve as a significant means to connect architecture to other forms of inquiry. These tendencies are well developed in the section. First, Vishaan Chakrabarti and his colleagues at SHoP Architects have produced a compelling way to describe and visualize the relationship of cities to sustainability generally considered. They identify the city as an important tool for adjusting human relationships to climate systems. Visualization strategies are crucial, as their article and the book from which it is drawn rely on innovative images, charts, and diagrams to communicate the central ideas of the text, to make that information more accessible, and to relate urban conditions to other forms of data and their potential consequences.

The essay by Dan Willis builds on Chakrabarti’s arguments (and those by another contributor to this book, David Owen) in favor of urban density, and then proposes a specific two-part agenda for contemporary architects who are concerned for the environment. Willis believes architects should be devoting attention to translating the sorts of spaces and environments that attract families to the suburbs into urban, most likely “verticalized,” equivalents. In addition, they must present these new urban visions in a manner that is likely to spark further professional interest and activity, thereby leading to greater public acceptance. Willis evokes early twentieth-century artist Hugh Ferriss and his book The Metropolis of Tomorrow as a model for the form, if not the style, of contemporary visualizations of desirable density.

Stephen Kieran, of KieranTimberlake, demonstrates the importance of representational tools to understanding how climates and other regional patterns can be engaged and expressed in a building. He examines the universal palliative of air conditioning and its effects on architectural design methods, and proposes, through the Ideal Choice Homes developed by his firm, how passive models can provide another option, on a mass scale. Stefan Al then discusses how complex urban forms in the Pearl River Delta have provided opportunities for energy efficiency according to their regional specificity. Here the regional effect on urban form is seen to be simultaneously cultural and climatic, with an emphasis on density allowing for highly efficient settlements.

The next building project to be highlighted in this section, the ParkRoyal on Pickering hotel/office complex in Singapore, by WOHA, is notable for the degree to which the building incorporates landscape elements throughout all of its levels. Indeed, to a great extent the building acts as a scaffold supporting all manner of native greenery, as well as sky-gardens, terraces, pools and waterfalls. This symbiotic relationship blurs the distinction between building and landscape. What would generally be considered discrete “systems,” separate from the living elements on, in, and around the building, are instead conceived as an interdependent network of devices that mediate climate and enhance quality of life. Thus the same flowers, vines, and shrubs that provide shade and evaporative cooling simultaneously create a suitable habitat for insects and birds.

Daniel Barber’s essay examines the history of architectural interest in climate region, through an analysis of the “Climate Control Project,” a joint effort through the American Institute of Architects and the shelter magazine, House Beautiful, which looked to the emerging science of microclimatology to offer parameters for new ways of building in the suburbs. The climatic region was here deployed explicitly, but also very generally, as it was determined that general design methods relative to climate are not easily generalized even across very small geographic areas.

Lateral Office offers three distinct visualizations of the region and its potential design effects. How we see the region – the terms, ideas, and potentials it contains – the firm proposes, frames the design projects that emerge. The different projects operate at different scales of design intervention, but in each case take the framework of the region as a means to determine that scale.

Muramoto demonstrates how Koji Fujii, the pioneer of environmental engineering in Japan in the 1920s, identified unique bioclimatic designs in traditional Japanese architecture, and modernized them with scientific environmental knowledge gained from his experimental house named “Chochikukyo.” He argues that the modern-day relevance of Fujii’s bioclimatic approach is that this house enhances awareness of the important threefold reciprocity between social, visual, and climatic conditions.

A science center by SMP Architects for a Philadelphia school is included as a case study of a very place- and climate-specific response to an urban infill site. The project is notable for its extremely clear and accessible drawings and diagrams, which explain the architects’ strategies for site utilization, energy generation, heating and cooling, natural ventilation, daylighting, rainwater harvesting, and the selection of appropriate materials and assemblies. Also worthy of noting is the degree to which the building and landscape design are integrated, with the intention of creating a didactic, self-sustaining ecosystem.

Rania Ghosn discusses the complex engagement with corn as a fuel crop, and how it has reframed the agricultural practices of the mid-west. Tracing the importance of government support, labor practices, chemical innovations, and the vagaries of the market, the physical transformation of the region is seen to be both immanent and implicated in a wide range of global forces. Keith Eggener then traces the work of Francisco Artigas, one of the most prolific modern architects in Mexico, focusing on how cultural and climatic aspects of the region elicited a range of design responses. His crystalline, cubic pavilions—built for top professionals, business leaders, powerful political families, film stars, and other native and foreign elites, featured in popular movies and television shows of the era, once reproduced in newspapers and magazines around the world – were acute and affecting responses to their physical and cultural settings.

The heavy timber roof and large overhang of Patkau Architects’ Gleneagle Community Center demonstrates how architecture can take advantage of existing sloped topography for passive energy design. Unique cross-sectional development under the big roof houses a large volume gymnasium that faces three floors of stacked program spaces with visual connections between them, where one can literally and metaphorically experience the dynamic “energy” flow of the Community Center.

Cities, Sustainability, and Resilience

As crucial as the concept may be, “sustainability” has become an over-marketed, hackneyed, and largely misunderstood term as it relates to urbanism. I define sustainability as the aspiration that human activity be made compatible with the long-term health and safety of the natural environment, which, in turn, would ensure the longevity of our own species. Sustainability is decidedly not Henry David Thoreau’s misanthropic vision of a virgin forest occupied by one person. In the contemporary context, it is not about camping, or visiting eco-resorts in areas that should remain untouched, or living in “green” McMansions in the wilderness. To the contrary, sustainability is about running toward people, not away from them. It is about embracing all of humanity in order to leave most of the natural world just that—natural. Put in the simplest possible terms, if you love nature, don’t live in it. Cities represent the best chance of realizing this aspiration of global sustainability in a rapidly growing world.

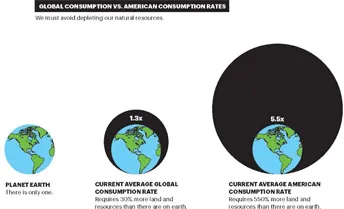

There is an alternative to the human self-loathing embedded in so much of environmentalism today: the rare belief that worldwide population growth and sustainability can be mutually compatible (Sachs 2005). While efforts to stem the rate of population growth are admirable, and through the implementation of economist Jeff Sachs’s extraordinary Millennium Development Goals we can and should reduce population growth rates, it remains clear that a world of 10 billion or more is inevitable by the year 2100.

Should environmentalists explicitly or tacitly focus on this growth as the primary problem, they do so at their own peril. Curtailing population growth is certainly one method to reduce resource usage, but who decides who gets to procreate and at what rate? Humanity’s history with such judgments is nothing short of bleak, with everything from genocide to forced sterilization representing the most terrifying moments in our collective past. Of course, as Sachs advises, we should actively promote birth control, prosperity, women’s education, public health, and all other measures that ethically reduce the rate of population growth. But again, we must have an environmental strategy that works with the reality of billions reaching the middle class worldwide in this century.

As human consumption continues to increase the world over, it is now abundantly clear that we use more natural resources than the world can replenish. We are, in our current state, collectively unsustainable. We must address resource usage at a global scale, and we must do so with a full embrace of every baby born. Individual feel-good actions have limited impact at a larger scale. We face a planetary environmental crisis, and must stop believing that solely through our individual choices will we solve this existential threat to current and future generations.

Sustainability, therefore, is not about the negligible benefits of the latest hybrid SUV, fluorescent light bulb, organic floor cleaner, or any of the other technological panaceas that attempt to absolve our gluttonous use of land and resources. Technology will not save us from ourselves, nor will the continual purchase of more stuff, however “green” it may be.

“If you love nature, don’t live in it.”

Addressing climate change at a global level will require a dramatic adj...