![]()

Section 1

Regional trends and country stories

![]()

1

East Asian democratization in comparative perspective

Viewing through the eyes of the citizens

Yu-tzung Chang and Yun-han Chu

Democracy is in trouble in every region of the world. Attempted democratic transitions are failing, new democracies are having trouble consolidating themselves, established democracies are suffering from a depletion of public trust in democratic institutions and there is a growing disillusion among many voters believing that existing political channels have failed to further their interests and preferences in a meaningful way while, at the same time, rising authoritarian powers radiate confidence in the effectiveness of their political systems (Diamond 2015).

How do East Asian democracies fare in the face of the headwind of global democratic recession (Diamond 2015)? Do East Asian democracies show any signs of democratic deconsolidation comparable to what Roberto Foa and Yascha Mounk have observed in the established democracies (2016; 2017)? In this chapter, we assess and ascertain whether democratic regimes in East Asia are still enjoying a solid foundation of popular support by applying an integrated framework of evaluating the popular perception of and orientations toward democracy. Thanks to the many innovations in survey design initiated by Asian Barometer Survey (ABS),1 we are in a position to study these crucial issues with a robust micro-foundation, i.e., seeing through the eyes of citizens, who are the final judge on width and depth of a regime’s popular foundation (Chu, et al. 2008).

Democracies become consolidated only when, in Linz and Stepan’s incisive phrase, not only all significant elites, but also an overwhelming proportion of ordinary citizens, see democracy as “the only game in town” (Linz and Stepan 1996:, 15). The consolidation of democracy requires “broad and deep legitimation, such that all significant political actors, at both the elite and mass levels, believe that the democratic regime is the most right and appropriate for their society, better than any other realistic alternative they can imagine” (Diamond 1999: 65). Thus the state of normative commitment to democracy among the public at large is crucial for evaluating how far the political system has traveled toward democratic consolidation.

The challenges of democratic consolidation in East Asia

Over the last four decades, as the tidal wave of the third wave democratization swept through the political landscape of the developing world and brought down numerous authoritarian regimes, people have taken for granted that democratic regimes by default enjoy a more robust foundation of legitimacy and thus are expected to be more resilient than non-democratic regimes in times of economic crisis and social turmoil. However, most recently there have been a number of developments that should prompt us to revisit this prevailing view.

As we enter the twenty-first century, the momentum of the third wave of democratization has gradually come to a halt and the large-scale trend of concurrent movement toward democracy has been arrested by the force of a new “democratic recession” (Diamond 2015). Many third-wave democracies have suffered from bad governance, political gridlock, setbacks in freedom and human rights or even democratic breakdown. Signs of democratic deconsolidation have taken place in many third-wave democracies, from Turkey, Ukraine, and Hungary to Bangladesh. Although the 2011 Arab Spring was a potential cause for optimism, thus far only Tunisia’s democratic transition has made visible progress, while democracy failed to take hold in Egypt, Yemen and Libya. During the late Third Wave, many transitions, perhaps even the majority, resulted in what Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way called competitive authoritarian regimes and others labeled illiberal democracies, semi authoritarian, electoral authoritarian or hybrid regimes (Levitsky and Way 2010). These governments held elections and tolerated limited opposition, but only within narrowly constrained political spaces delimited by the incumbents. At the same time, authoritarianism remains a fierce competitor to democracy in Asia, Middle East, Africa and the vast region of the former Soviet Union.

In East Asia, in particular, liberal democracy has yet to establish itself in the region’s ideological arena as “the only game in town,” i.e., the only acceptable mode of political legitimacy, as witnessed by the sustained interest in the debates over Asian values, the Chinese model of development, and Asian meritocracy (Bell 2015). Nearly forty-five years after democracy’s third wave began with the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, liberal democracy has yet achieved Fukuyama’s (1992) expected historical triumph. This reality is very apparent in East Asia, where, despite decades of economic growth and rapid social transformation, most East Asians do not live under democratic governments. As Huntington (1968; 1991) has pointed out, East Asia is a site of competition between civilizations. The reasons for this include the region’s long history of human civilization, its diverse cultural heritage, the resiliency of the competing non-democratic political models and the strong presence of Sino-US strategic rivalry.

Before the arrival of Western modernization in the nineteenth century, East Asia had its own political and economic hierarchy and international order. East Asian civilization is marked by the diversity of its cultural heritage and forms of social organization, including Confucian culture, Buddhist culture and Islamic culture. The presence of these cultural traditions forms the backdrop to conflicts between traditional and modern values during the process of modernization. According to some observers, major cultural traditions in the region, including Confucianism and Islam, may be incompatible with democracy (Huntington 1984; 1991).

East Asia is also a fertile soil for resilient non-democratic regimes competing with the model of representative democracy. The recent economic rise of China has led many to view the “China Model” as a viable alternative to Western democracy.2 After China’s economic success was showcased to the world at the Beijing Olympics, the intellectual debate over whether China has embarked on an alternative path to modernization has gathered momentum. Prior to this, the rise of East Asia’s “four little dragons” and the public pronouncements of Singapore leader Lee Kuan Yew resulted in widespread discussion surrounding “Asian values.” Thirty years later, the rise of China has led to a reemergence of this debate. Does this mean that there is a genuine alternative to Western-style democracy? The Thai military coup in 2006, and the continuing failure of countries such as Malaysia and the Philippines to strengthen democracy, provide a stark illustration of the continuing challenges for democratic consolidation in the region. Even Indonesian democracy, widely held up as an exception to the democratic recession elsewhere in the world, has been “stagnating” in recent years under attack from anti-reformist elements (Mietzner 2012).

East Asia in comparative perspective

East Asia is not unique in its uneasy relationship with democracy due to traditional culture or authoritarianism legacies. Regional barometer surveys that cover Africa, Latin America, the Arab world and South Asia likewise show that support for democracy can be thin. But in Latin America and Africa democratic legitimacy has declined least in the best-governed and most democratic countries, while in East Asia it is in precisely such countries – Japan, Korea and Taiwan – that democratic legitimacy has been most fragile (Chu et al. 2008; Diamond and Plattner 2008; Diamond, Plattner and Chu 2013).

According to a Freedom House report in 2017, of the 195 countries assessed, eighty-seven (45%) were rated Free, fifty-nine (30%) Partly Free and forty-nine (25%) Not Free.3 East Asia, however, lagged behind the global trend. The region has long been the cradle of “developmental authoritarianism,” with Japan being the lone liberal democracy, and for decades a one-party dominant system at that. At the time the Fourth Wave of ABS ended in 2016, only five of the region’s eighteen sovereign states and autonomous territories were ranked “free” by Freedom House’s standards of political rights and civil liberties. Among the five, only four (South Korea, Taiwan, Mongolia and Indonesia) had undergone democratic transition during the time span of the third wave. Two recently re-democratized systems, Thailand and the Philippines, suffered serious backsliding and were downgraded by Freedom House to “partially free.” The bulk of the region was still governed by one-party authoritarian and electoral-authoritarian regimes. The region not only lagged the global trend of third-wave democratization but also was not immune from worrisome trend of global democratic recession. Furthermore, with the shift of the center of regional economic gravity from Japan to China, East Asia become perhaps the only region in the world where newly democratized countries become economically enmeshed with non-democratic countries.

Even after democratic transition, few of the region’s former authoritarian regimes were thoroughly discredited. Many people recalled the old regimes as having delivered social stability and miraculous economic growth and as seemingly less susceptible than democracies to money politics. Many of the old authoritarian regimes had allowed some organized opposition and limited electoral contestation, so citizens did not experience as dramatic an increase in the area of political rights and freedoms after the transition as did citizens in third-wave democracies in other regions (Chang, Chu and Park 2007).

In terms of regime performance, many of East Asia’s new democracies struggled with governance challenges – political strife, bureaucratic paralysis, recurring political scandals, financial crises and sluggish economic growth. At the same time, the region’s more resilient one-party authoritarian and electoral-authoritarian regimes, such as China, Vietnam, Singapore and Malaysia, were seemingly able to cope with complex economies, diverse interests, economic globalization and financial crises. These historical and contemporary benchmarks tended to generate extraordinarily high expectations for the performance of democratic regimes.

To assess the challenges of democratic consolidation in East Asia, we draw on the empirical data that reveal how the citizens perceive and evaluate the state of democracy in their given country. More specifically, we examine how far the citizens think their country has traveled down the road of democratic progress thus far, to what extent the citizens have acquired strong and deep normative commitments to democratic form of government, whether the majority of the citizenry are satisfied with the way democracy works, how much public trust that democratic institutions are enjoying and to what extent the political system lives up to the citizens’ expectation about controlling corruption, the most cited factor that erodes the legitimacy of the regime. By analyzing the data from ABS across four waves, we provide a systematic and longitudinal assessment of the state of democracy in East Asia.

The data from South Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, the Philippines and Thailand allow us to compare popular legitimation of democracy across the region’s five new democracies. Data collected from Japan, Hong Kong and China throws light on popular beliefs and attitudes in societies living under different kinds of regimes: the only long-established democracy in the region – a former British colony that has enjoyed the world’s highest degree of economic freedom but witnessed its momentum of democratic transition slow after retrocession to Chinese control in 1997 – and a one-party authoritarian regime wrestling with the political implications of rapid socio-economic transformation while resisting any fundamental change in its political regime.

Perceived extent of democracy

The ABS introduced a direct way to find out how far the citizens think their country has traveled down the path of democratic development. The respondents were asked to indicate where their country stand under the present government on a 10-point dictatorship-democracy scale. A score of 1 means “complete dictatorship” whereas a score of 10 indicates “complete democracy.” Since the mid-point of the scale lies between 5 and 6, those in the top half (6 or above on the scale) may be seen as locating the country in the democratic territory.

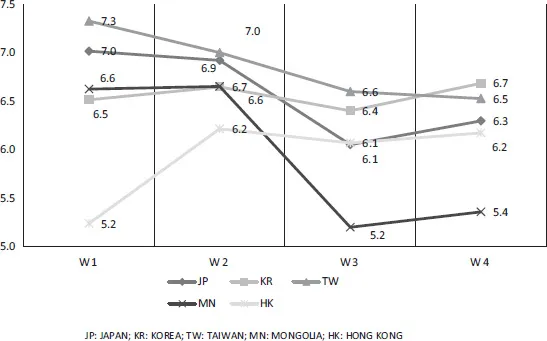

As shown in Figure 1.1, with the exception of Hong Kong, the overwhelming majority of East Asian people is of the opinion that their democracy has not made significant democratic progress over the last fifteen years despite the fact that their countries are rated by Freedom House as “Free.” On the contrary, the popular perception is that their democracy has suffered some backsliding with the rating of the country’s level of democratic development gradually declining. For example, whereas Taiwan citizens previously rated the island’s democratic progress at 7.3, it is now reduced to 6.5. In Japan, this score has fallen from 7.0 points to 6.3. The most worrisome nation is Mongolia, where the score has fallen from 6.5 to 5.4. Hong Kong’s story is encouraging but not impressive. In the eyes of Hong Kong people, this former British colony has made some progress from a rather low level of democratic development over the recent decade probably thanks to the growing mass demand for direct popular election of the chief executive of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) under the Basic Law.

Figure 1.1 Perceptions of current regimes

Support for democracy

A necessary condition for the consolidation of democracy is met when an overwhelming proportion of citizens believe that “the democratic regime is the most right and appropriate for their society, better than any other realistic alternative they can imagine”(Diamond 1999: 65). By this standard, East Asia’s young democracies have not yet achieved a strong and resilient popular base for democratic legitimacy. The four waves of the Asian Barometer Survey confirm that many East Asian citizens still possess amb...