eBook - ePub

The Promise of Representative Bureaucracy: Diversity and Responsiveness in a Government Agency

Diversity and Responsiveness in a Government Agency

Sally Coleman Selden

This is a test

Share book

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Promise of Representative Bureaucracy: Diversity and Responsiveness in a Government Agency

Diversity and Responsiveness in a Government Agency

Sally Coleman Selden

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This text on representive bureaucracy covers topics such as: bureaucracy as a representative institution; bureaucratic power and the dilemma of administrative responsibility; and representative bureaucracy and the potential for reconciling bureaucracy and democracy.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Promise of Representative Bureaucracy: Diversity and Responsiveness in a Government Agency an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Promise of Representative Bureaucracy: Diversity and Responsiveness in a Government Agency by Sally Coleman Selden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

—————

Bureaucracy As a Representative Institution

Decision making that values diversity multiplies the points of access to government, disperses power, and struggles to ensure a full and developed rational dialogue. Public policy then becomes “the equilibrium reached in the group struggle at any given moment.”—Lani Guinier (1994, 175)

Administrative decisions are often, in a broad sense, political decisions. In government departments and agencies, for example, administrators charged with responsibility for program implementation ultimately shape the nature of many public policies.1 For example, Charles T. Goodsell (1985, 41) found substantial variation in the “tone of voice” used in Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) food stamp application forms and instructions. Some offices addressed potential clients positively in their program literature, while others were negative and threatening. The tone of the materials sends a powerful message to potential applicants about the organization’s climate and attitude toward clients. Government bureaucrats exert influence over the formation of public policy every day, often in small ways, but just as frequently in larger ways (Krislov 1974). Consequently, the control of administrative power in public service is extremely important, especially in a democratic system. Traditionally, scholars have focused on formal constitutional mechanisms and less formal strategies emphasizing public access, efficiency, and competence to reconcile administrative power and democracy. Today, however, the problem of ensuring administrative responsibility and responsiveness to the public remains a major concern in public administration (Gilbert 1959; Larson 1973; Meier 1993b; Mosher 1982; Waldo 1952).

Problems of bureaucratic responsibility emerge because classified civil servants are at least three steps removed from the American electorate (Mosher 1982). Elected officials appoint top-level administrators who in turn direct organizations staffed by civil service employees. Furthermore, the civil service personnel system is designed to protect employees from political pressure. Employees in the classified service cannot be disciplined, transferred, or promoted for political reasons. As a result, some scholars contend that presidential and congressional oversight alone are inadequate means of ensuring bureaucratic responsibility (Gilbert 1959). When this concern is coupled with the fact that civil servants exercise considerable administrative discretion at all levels of the public bureaucracy, problems of accountability and responsibility become critical.

As a consequence, a number of scholars have endorsed the view that bureaucratic power to mold public policy can be made more responsive to public interests (and will therefore better serve democratic principles) if the personnel in the bureaucracy reflect the public served, in characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and gender (Rourke 1978, 396). This idea forms the rationale for the theory of “representative bureaucracy.” The argument is premised on the belief that such attributes lead to certain early socialization experiences that in turn give rise to attitudes and values that ultimately help to shape the behavior and decisions of individual bureaucrats (Kranz 1976; Krislov 1974; Saltzstein 1979). Proponents contend that representative bureaucracy provides a means of fostering equity in the policy process by helping to ensure that all interests are represented in the formulation and implementation of policies and programs (Denhardt and deLeon 1995; Saltzstein 1979). According to Samuel Krislov (1974, 21), a prominent scholar on the subject, “the greater the degree of discretion imputed to a bureaucracy, the more vigorous its functions, the stronger the need for the type of accountability and sense of responsibility implied by the call for representativeness.”

The Issue of Bureaucratic Representation

J. Donald Kingsley’s (1944) book, Representative Bureaucracy, is the first work to systematically examine the issue of public work force representation. Kingsley, who studied the operation of the public service in Great Britain, advanced the notion that the civil service should reflect the characteristics of the ruling social class because the civil service must be sympathetic to the concerns of the dominant political leadership. Kingsley’s work was grounded on the notion that the representativeness of the public bureaucracy should be measured in terms of social class. Operating from that premise, V. Subramanian (1967) documented middle-class dominance in the bureaucracies of several nations, including Great Britain, France, India, and the United States. Later work by Kenneth J. Meier (1975) focusing on the American civil service measured bureaucratic representativeness in terms of a variety of factors such as age, education, income, size of birthplace, social class, region of birth, and father’s occupation. Subsequent interest in the racial, ethnic, and gender-based representativeness of the American bureaucracy emerged in part because of the relative underrepresentation of minorities and women in middle and higher levels of the civil service and because important attitudinal and opinion chasms often form along racial, ethnic, and gender lines.

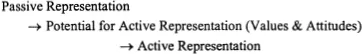

The central tenet of the concept of representative bureaucracy is that passive representation, or the extent to which a bureaucracy employs people of diverse demographic backgrounds, leads to active representation, or the pursuit of policies reflecting the interests and desires of those people (Meier 1993b; Meier and Stewart 1992; Mosher 1982). For example, African-American administrators may be more supportive of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) policies than their white counterparts, or Hispanic police officers may be more empathetic toward Hispanic suspects than non-Hispanic officers. This is plausible because of the belief that individuals of like backgrounds undergo similar socialization experiences. Those experiences lead to the formation of attitudes and values that are subsequently linked to behavior. The theory suggests that minority administrators, for example, will share attitudes and values with minorities in the general population and will therefore act to represent minority interests when opportunities to do so arise in the policy process.

Some scholars have argued, however, that the link between demographic background and attitudes/values is weakened or overcome by organizational socialization (Meier and Nigro 1976; Mosher 1982). Socialization is an ongoing learning process that continues once an individual enters an organizational setting and may be used to create a culture or environment that encourages organizational commitment and loyalty. When the organization’s mission or culture does not emphasize minority or female interests, socialization to the organization may weaken the link between the demographic background of administrators and active representation of minorities and women (Meier and Nigro 1976; Romzek and Hendricks 1982). For example, representation of women and minorities is not central to the mission of the National Institutes of Health or the Central Intelligence Agency. In such agencies, the acceptance of organizational norms and values will likely decrease representative bureaucracy. Agencies with a mission that includes representation of particular groups, such as the EEOC and the Commission on Civil Rights (CRC), are more likely to inculcate in employees values that include active representation of particular groups.

Benefits of Representative Bureaucracy

A bureaucracy that reflects the diversity of the general population implies a symbolic commitment to equal access to power (Gallas 1985; Meier 1993c; Mosher 1982; Wise 1990). The symbolic role results from both the personal characteristics of distinctive group members, and the assumption that because of these characteristics, the bureaucracy has had experiences in common with other members of that group (Guinier 1994). When members of distinctive groups become public officials, they become legitimate actors in the political process with the ability to shape public policy.

Groups previously not represented may provide genuine expertise, valid information, and more accurate reflections of group preferences (Kranz 1976). To a degree, individuals are limited in their understanding of an issue by their own experiences and frames of reference. When a group is not represented, its concerns and preferences are less likely to be voiced and brought to bear on decisions rendered. A more diverse decision-making entity suggests that a wider range of perspectives will be considered. The presence of underrepresented groups should enhance the majority group’s empathic understanding and responsiveness to previously underrepresented or excluded groups (Kranz 1976).

A representative bureaucracy should also influence how items are prioritized on the agenda (Kingdon 1984; Guy 1992). According to John Kingdon (1984, 160), agendas change either because “incumbents in positions of authority change their priorities and push new agenda items; or the personnel in those positions changes, bringing new priorities onto the agenda by virtue of the turnover.” As the share of women and minorities in decision-making positions increases, subjects of particular interest to these groups have a greater chance of becoming a priority on the agenda (Guy 1992). Some scholars, for example, have gauged increased responsiveness by examining the discourse on and adoption of policies and practices that target specific groups (Tamerius 1995). A bureaucracy that reflects the demographic composition of society will incorporate a greater spectrum of opinions and preferences into the agenda-setting and decision-making processes and, as a result, should be more responsive to those groups (Kranz 1976).

Several scholars also suggest that groups previously underrep-resented or unrepresented will be more closely bound to the agency as their representation increases and, as a result, they will be more inclined to cooperate and to co-produce with bureaucratic agencies (Kranz 1976; Shafritz, Hyde, and Rosenbloom 1986). Potential clients, for example, may be more apt to participate in government programs when they identify and are comfortable with program administrators (Hadwiger 1973). Similarly, they may avoid taking part in programs if they are intimated by or feel awkward around program personnel.

The last benefit to be highlighted is that a more representative bureaucracy will lead to a more efficient use of human resources (Kranz 1976). Previously excluded groups, such as minority females, are readily available in the labor pool.

Since at least the 1960s, government jurisdictions in the United States have pursued a number of equal employment opportunity and affirmative action strategies designed to promote work force diversity. Recently, these efforts have been under siege, and questions have been raised about the fairness of affirmative action policies designed to advance the opportunities of previously underrepresented groups. To inform policy makers’ decisions regarding the benefits of a diversified work force, however, it is important to consider some of the empirical questions that emerge from the concept of representative bureaucracy.

The first issue that arises is whether or not the bureaucracy broadly reflects the demographic characteristics of the population, and what factors explain variations in representation. Are people of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds employed? Are women as well as men employed in important positions? Following these questions is the issue of whether or not increasing work force diversity makes a difference in organizational operations and policies. Has increasing female, minority, and ethnic employment had an impact on policy outputs?

Empirical Research on Representative Bureaucracy

There are three major components to the theory of representative bureaucracy:

Empirical research on the topic follows these components closely. Some researchers have focused on the demographic composition of the bureaucracy as a test of representation, some have explored attitude congruence between bureaucrats and represented groups, and others have examined the effect of minority representation on policy outputs and outcomes. The bulk of previous empirical research has concentrated on passive representation, that is, whether or not the bureaucracy broadly reflects the composition of society in terms of gender, race, and ethnicity (Hellriegel and Short 1972; Nachmias and Rosenbloom 1973; Gibson and Yeager 1975; Grabosky and Rosenbloom 1975; Meier 1975; Hall and Saltzstein 1977; Rose and Chia 1978; Cayer and Sigelman 1980; Smith 1980; Dometrius 1984; Lewis 1988; Kellough 1990a; Kim 1993; Page 1994). Also, a number of scholars have looked at determinants of female, minority, and ethnic employment levels in municipalities and the federal government (Dye and Renick 1981; Eisinger 1982; Welch et al. 1983; Riccucci 1986; Saltzstein 1986; Stein 1986; Mladenka 1989a, 1989b, 1991; Kellough 1990a; Kellough and Elliott 1992; Kim 1993; Cornwell and Kellough 1994).

A second category of research has explored the relationship between demographic characteristics and bureaucrats’ attitudes. These studies have yielded contradictory results, which may be due in part to different approaches used to measure attitude congruence. For example, in ten of the twelve policy areas examined, Kenneth Meier and Lloyd Nigro (1976) found that organizational socialization was more important than demographic factors in explaining attitudes. In one case, welfare, the influences of social origins and organizational socialization were the same. On the issue of improving the conditions of minorities, demographic factors (including race) were more important than organizational socialization. David Rosenbloom and Jeannette Featherstonhaugh (1977), on the other hand, concluded that despite the effects of agency socialization, social characteristics continued to influence the attitudes of civil servants. They found that African-American civil servants tended to hold attitudes similar to African Americans in the general population when compared to white federal bureaucrats.

Empirical research examining the impact of passive representation on policy outcomes has been more consistent. Meier and Stewart’s (1992) analysis revealed that the presence of African-American street-level bureaucrats (e.g., schoolteachers) had a significant effect on policy outcomes favoring African-American students. Meier (1993a) later replicated these findings for Latinos. He also tested the hypothesis proposed by Frank Thompson (1976) and Lenneal Henderson (1979) that a critical mass of minority administrators is needed under some circumstances before active representation occurs. Meier (1993a) found evidence to support this sup...