![]()

Part One

The Context of Character

![]()

Chapter 1.0

Introduction

This book has evolved from the long experience of the authors in tackling the questions: what exactly constitutes the character of this place and how is that character communicated with and to others? Other questions have followed: how can communities and individuals communicate their responses to the character of an area, beyond generalities and indistinct feelings, with professionals and politicians in an effective and precise way, using something like a common language? Furthermore, are there techniques of characterisation that can be used to facilitate this common language? Finally, we regularly ask ourselves the questions: So what? Can characterisation be used as something more than a measure to protect a place (which may or may not be valid, depending on circumstances); can characterisation be integrated more fundamentally than it is into the planning, design and placemaking process? If so, how might it influence present practice?

Defining Character

How, precisely, do we define the character of a place? We use the term so widely within the fields of planning, conservation and urban design, assuming that its definition is self-evident. Yet so much can hang on this word, often used as a measuring rod by which we can assess whether a place is worthy of protection, or whether a design proposal is appropriate. It is used in public inquiries and policy documents as well as being informally used in ordinary conversations to help describe a place or building.

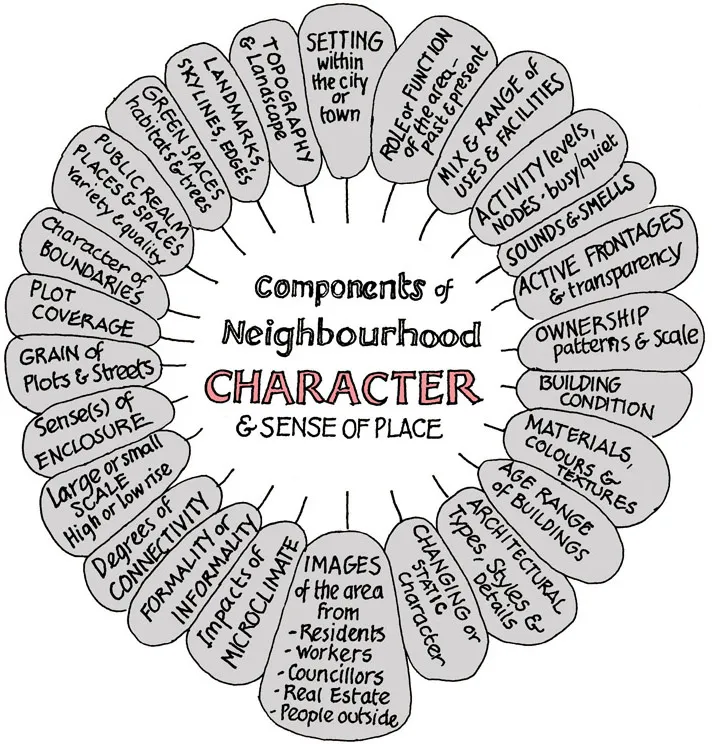

The diagram in Figure 1.0.1 shows the different components that are likely to comprise the character of an urban, suburban or village area. They are depicted in circular format, to indicate that there is no implied hierarchy of components. In particular contexts some components may assume greater emphasis, whilst others may hardly have any impact, and this will vary. It will be seen that there is, perhaps as expected, a significant representation of terms relating to the physical appearance of an area, building types, forms, materials, styles and so on. Additionally, the spatial qualities of sense of place and enclosure, scale and landmarks are included, as are topography, landscape and layout of the area. Importantly, levels of activity and building uses, and other factors affecting character are identified: the sounds, smells and textures of a place, its sense of age and the visible reminders of past uses and the image and associations people have with an-area.

1.01 The components of character

These factors are rarely perceived in isolation; they overlap and are intertwined with-others in the diagram. Therefore it is our task to identify the key relationships between these factors, as much as the factors themselves.

Moreover, character is a dynamic concept in that it changes and evolves. An area may have had one type of character a century ago, another a generation ago and have yet another today, but there may be signs that in the near future it might be more affluent or, indeed, may be declining. In this process of evolution the present will always retain some remnants of the past; in older buildings whose original purpose has become obsolete, in street layouts and alignments, in place names and in landmarks. Today we tend to value these reminders of our roots and incorporate them into our present environments by sensitive re-use and recognising that the ‘patina of age’ engages our delight in places. However, it is still not always so, and the cherished character of a place can be lost through widespread demolition and insensitive replacement development.

The term character is often considered to be synonymous with ‘good’ or ‘positive’. However, whilst some places may have a positive character, in that the people who live, work or visit there regard it as a pleasant, stimulating or relaxing place to be, there are other places that have a negative character. In these places, the atmosphere might be alienating, threatening or run-down. In yet other places, the character may be said to be neutral, in that whilst generally acceptable, it might be monotonous, lack any sense of stimulation, be devoid of any sense of focus or have little to distinguish it from other areas.

It is the job of architects, planners, urban designers and other ‘place shapers’, first, to work with communities to identify the character of neighbourhoods, to identify what is valued and what is of value (there may be a difference here), and to pinpoint the negative and neutral aspects of the character. Second, the task is to develop strategies whereby the positive character can be conserved and enhanced, where the negative can be sensitively and appropriately replaced, and to propose interventions in the neutral areas where, for example, improvements in landscape, diversity or legibility may be appropriate.

We argue that there is a difference between a place that is perceived as attractive and well kept and somewhere that may be apparently less attractive (possibly as it is unfamiliar or may be somewhat run-down), but that is significant. Both could have positive aspects of character.

All the factors identified within the diagram will be explained and discussed in Part Two of the book.

Defining Characterisation

Characterisation involves the process of capturing the character of a place through a range of skills and insights. Ideally it is a collaborative activity involving perceptive observation (of people and the built environment), notation and graphic skills of various types, research, editorial and management abilities. However, we stress that the process should not be judged as only being effective in relation to the size of a report, or to the length of time and human resources expended on it. We demonstrate that effective characterisations can be undertaken over a short period of time, with a relatively small number of people, preferably a mix of local people and professional facilitators. This last point ensures a balance between local knowledge and insights and a certain detachment to see the particular project within a wider context.

Characterisation requires the exercise of judgement and evaluation; it is more than the pure description of the neighbourhood. We are looking for what is significant that defines the place; what is typical in the pattern of built forms and layout; and what may be unique and what stands out. ‘Unique’ can be an over-used concept; rarely is somewhere absolutely unique in that there is nowhere like it. What might be unique is the mix of features that are seen in a different mix elsewhere in similar neighbourhoods. It is important not to be so inwardly focussed on the neighbourhood being characterised that we don’t compare it with adjacent areas or with other similar areas elsewhere.

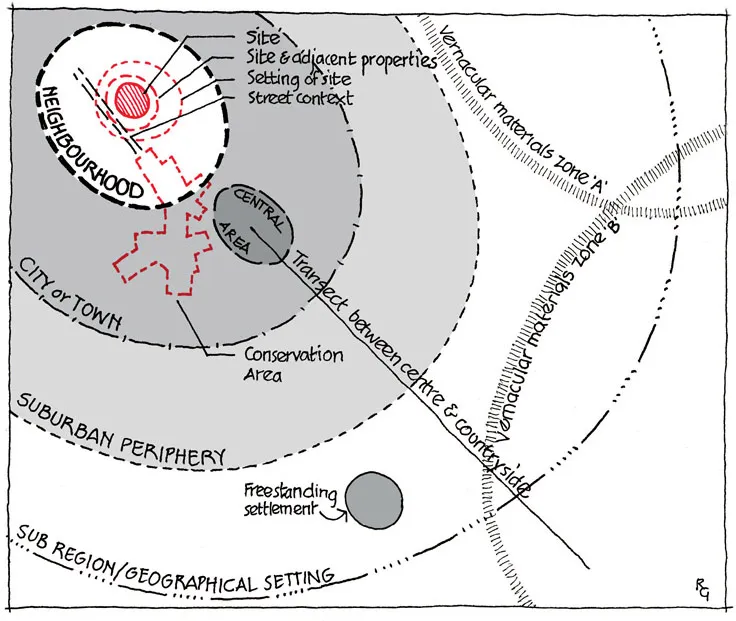

Characterisation can be undertaken at a variety of scales; from the national and regional, to landscapes and to local authority areas. This book focuses on the smaller scale of the urban area and in particular on the patchwork of neighbourhoods, districts or quarters. In doing this, the influence of the larger scales will be taken into account where relevant (see Figure 1.0.4).

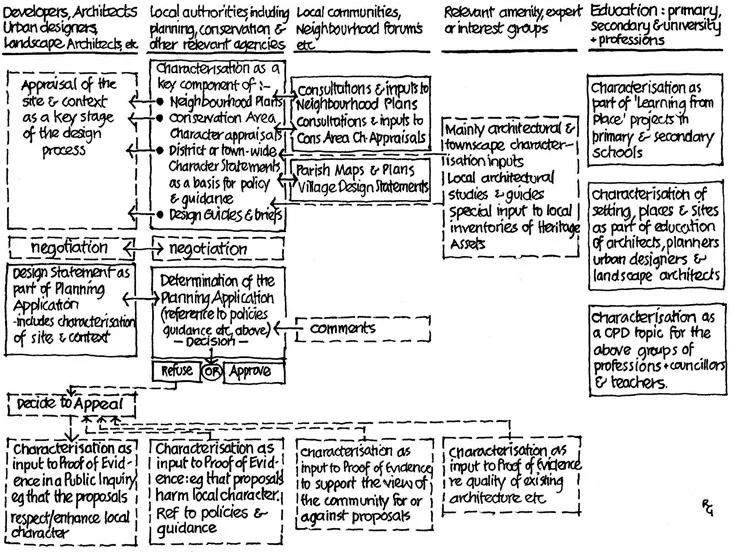

1.02 Issues involving character in the planning and design process

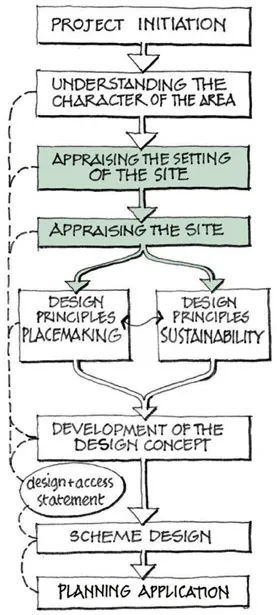

1.03 Characterisation in the urban design process

1.04 Characterisation can take place at a variety of overlapping scales

Defining Neighbourhoods

An extensive literature has accumulated on neighbourhoods over the past 80 years or so in the United Kingdom and United States, regarding their definition, composition, image and related policies. Within the context of this book, we generally subscribe to the concept of neighbourhoods adopted by Hugh Barton and Marcus Grant, co-authors of our ‘sister’ publication Shaping Neighbourhoods.

The definition of ‘neighbourhood’ … is one based on resident perceptions. As such they are normally residential areas of distinctive identity, often distinguished by name, and bounded by recognisable barriers or transition areas, such as railway lines, main roads, parks, and the age or character of buildings (often associated with social or land use differences).

Neighbourhoods thus defined vary in size widely according to local circumstances, but a typical size might be 4,000 to 5,000 (people). They are often large enough to include a primary school and some local shops. However, … they may not coincide with local catchment areas. The local high street [main street], with its range of [town centre] facilities will sometimes be at the edge of the neighbourhood.

(Barton et al.: 32)

Taking this definition, neighbourhoods occupy the space between the whole town, or similar urban area (with its range of commercial, industrial, services, administrative, educational-and cultural uses), and the ‘home place’ comprising ‘the individual streets, squares, blocks … that make up the patchwork of the neighbourhood’ (ibid.).

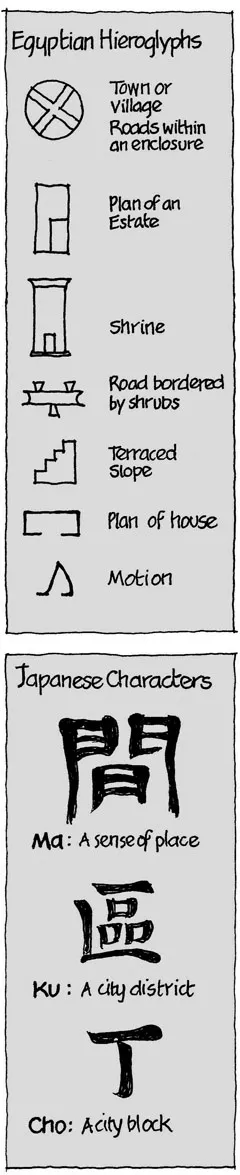

1.05 Symbols describing place, in ancient Egypt and Japan

Neighbourhoods are usually ‘fuzzily’ defined, with different people having different views on the boundary of the area. Neighbourhoods will sometimes overlap with the town or city centre. Moreover, administratively delineated neighbourhoods, parishes, or quarters, may or may not coincide with neighbourhoods as perceived by the residents.

A neighbourhood will generally possess some focus of facilities which generate a catchment area of local streets. It will have a sense of local distinctiveness.

We share the view of Shaping Neighbourhoods that neighbourhoods are ecosystems; in that they are human habitats with networks of interacting factors, uses, activities, social and community relationships, culture and lifestyles, which are reflected in and supported by an infrastructure of buildings of appropriate size, affordability and tenure. Moreover, the public realm of green and ‘hard’ spaces also contributes to the ecology of the neighbourhood. If this ecology is working, it is reflected in the well-being of the residents; they feel safe, can express themselves, there is a high degree of human interaction and conviviality. If it is dysfunctional, the neighbourhood becomes stressed in various ways, for example socially, economically and in terms of its general condition.

Notation: Towards a Common Language?

A theme that runs through the book is that the quality of communication between neighbourhood communities, local politicians and professionals such as planners and urban designers should be substantially improved. Many professionals, it appears to residents, seem to communicate both graphically and verbally in what seems unfathomable jargon, whereas professionals are often dismayed that ‘lay’ people seem unwilling or unable to discuss-matters regarding their surroundings beyond generalities and clichés.

Despite the English language having an extensive vocabulary, it seems that it has limitations when we attempt to evaluate buildings and the urban landscape. We believe that many readers will acquire an enlarged vocabulary of spatial and design terminology as they progress through the book, from the annotated diagrams, captioned illustrations and margin notes as well as throughout the text. The quiz sheet, devised for use with in-house cou...