![]()

Chapter 1

Sound Production vs. Sound Reproduction

Before getting into sound reproduction, the title of this book, it is good to have a look at where it all begins: in live performances—sound production. We may like to think that our audio systems are capable of reconstructing such experiences, but that is simply not possible. Even today, with nearly unlimited bandwidth available, two-channel stereo is the default format. There is no doubt that stereo can be greatly entertaining, and at times can make us feel close to the real experience. But it is sad to say that many recordings can be well described as: left loudspeaker, right loudspeaker and phantom center. This is mono, mono and double mono. Listened to through headphones it becomes left ear, right ear and center of the head. The essence of the music can be conveyed, but any semblance of acoustical space and ambiance is missing. Skillful microphone setup and signal processing by recording engineers can improve things, but at best stereo remains a directionally and spatially deprived format, and an antisocial one, requiring a sweet spot.

We need more channels to capture, store and reproduce even the essential perceptions of three-dimensional sound fields. This is what the movie world has known for decades, and now cinemas have as many as 62 channels in the immersive sound formats. That is excessive for musical needs, but more than two would be nice. Fortunately there are examples of excellent multichannel music, and indications that a binaural version of it will be a part of virtual reality systems. Stay tuned.

On the scientific side, the origins of modern acoustics lie largely in the domain of halls for the performance of classical music. Whether this music appeals to a person or not, the basic perceptions generated by these live performances are generously shared within all recorded music, whatever the genre. Reverberation, spaciousness, envelopment and so on are all simply pleasant perceptual experiences, and recording engineers have been provided with elaborate electronic processors allowing them to be incorporated into any kind of music, adding to the artistic palette. The future is sounding good.

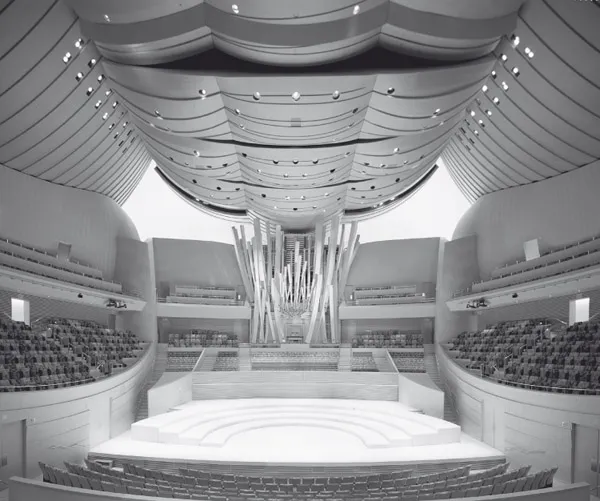

1.1 Live Classical Music Performances— Sound Production

I have an approximation of a state-of-the-art sound reproducing system at home, and have always had such systems, gradually improving over the years. As good as they have been, the real thing is a very different and more satisfying auditory event. Dressing up, driving, perhaps eating out, crowds of similar-minded people, the overall visual atmosphere all add to the experience, but the aural components of the experience are the real treat.

I attend about a dozen live concert hall performances a year. Sitting, watching people take their seats and the orchestra assembling on stage, I am aware of a pleasing sense of a large space—I hear the space that my eyes see. This does not happen at home. As the musicians tune up and practice difficult passages, the timbres are enriched by countless reflections—repetitions that give our hearing system more opportunities to hear subtleties. I can localize individual musicians, and even though the sound begins at those locations, the timbres linger in the decaying reverberation all around me. When the music starts, it all magnificently comes together. The sound of the hall is an inseparable part of the performance: rich timbres combined with enveloping space. I am “in” the performance. This is a complex listening experience, allowing one to begin to discover what contributes to an engaging final product. However, it is interesting to consider that with different musicians, instruments, conductors and halls, the “reference” is really not a constant entity.

In fact, one can correctly assert that a live concert hall performance is what it is at the time, and may never be repeated again. It is sound production.

It is interesting to note that, even in different halls, the essential timbres of voices and musical instruments remain remarkably constant. We have considerable ability to separate the sound of the source from the sound of the hall. In other words, we appear to adapt to the room we are in and “listen through” it to hear the sound sources. A variation on this interpretation is that we engage in what Bregman (1999) calls “auditory scene analysis,” and we “stream” the sound of the voices and instruments as significantly separate from the sound of the room. We do this to such an extent that one can focus on the sound from one section of the orchestra, suppressing others. Two ears and a brain are remarkable. If a concert hall performance seems to lack bass, as some do, the inclination is to blame the hall, not the musicians or their instruments. We instinctively know where the blame lies.

Later in the book we will discuss the elements of these auditory events from both perceptual and measurement perspectives. For now, it is sufficient to note that reproducing a concert hall experience means delivering both the timbral and the spatial components. This is not easy.

Achieving satisfactory reproductions of these performances is partially determined by hardware: the electronics, the loudspeakers and the rooms. These are things consumers can choose and manipulate to some extent. But the most important contribution comes from the “system”:

Figure 1.1Los Angeles County Music Center’s Walt Disney Concert Hall Auditorium.

- ■The number of channels and the placement of the loudspeakers and listeners for playback.

- ■The microphone choice and placement, mixing/sound design, and mastering performed in the creation of the recording.

If the “system” does not allow for certain things to be heard, disappointment is inevitable. The existing system evolved within the audio industry itself and is being implemented by professionals operating within it. These are key factors in our impressions of direction and space, and there is persuasive evidence that spatial perceptions are comparable in importance to timbral quality in our overall subjective assessments of reproduced sound.

Time-domain information, the reverberation, is an important clue to the nature of the performance space. It can be conveyed by a single channel—mono—but it is a spatially “small” experience, with all sound localized to the single loudspeaker. Adding more channels allows for a soundstage, conveyed by the front channels: the lateral spread of the orchestra, with depth. There is also a more subtle component: apparent source width (ASW), or image broadening, wherein sounds acquire dimension, and an acoustical setting; some call it “air” around the instruments. Two channels suffice for a single listener in the symmetrically located “stereo seat,” but multiple listeners or a single listener not in the stereo seat require the addition of a center channel to prevent the phantom image soundstage from distorting and ultimately collapsing to the nearer loudspeaker. The perception of being “in” the space with the performers—envelopment—is hinted at in good stereo recordings, absent from many, but is more persuasively delivered by multichannel recordings, with side and other channels providing long-delayed lateral reflections that contribute to both image broadening and envelopment. It is the length of the delays that creates the impressions of large space, something that limits the spatial augmentation possible with multidirectional loudspeakers in small listening rooms. In fact, envelopment is, according to some authorities, the single most important aspect of concert hall performance.

As good as stereo can be, more channels are better for a single listener, and most definitely for multiple listeners. Unfortunately the 5- or 7-channel options almost universally used in movies have been not been commercially successful in the music domain, even though they are capable of more engaging reproductions. The new “immersive” formats, employing even more channels and loudspeakers, were created for movies, where they provide exciting spatial dynamics, but some demonstrations of music programs provide compelling impressions of real concert halls or cathedrals, even as one moves around the listening room. The two-ears, two-channels relationship works for headphones, but is spatially deprived for loudspeaker reproduction. This topic will be discussed in more detail later in Chapter 15.

1.2 Live Popular Music Performances— Sound Production

As pleasurable as the classics are, the majority of our entertainment falls into the numerous subdivisions of what is collectively called “popular” music. The recording methods used are also shared with most jazz we hear. Most of what we listen to is captured by microphones located unnaturally close to voices and musical instruments, or electrically captured without any acoustical connection, and then mixed and manipulated in the control room of a recording studio. The “performance,” the art, is what is heard through the monitor loudspeakers during the mixing and mastering operations. The era of large, expensive recording facilities is fading, as more recordings are done in converted bedrooms or garages in homes. The wide availability of sound mixing and processing programs, and the low cost of powerful computers, has given almost anybody access to capabilities that once were the exclusive domain of elaborate recording studio facilities. This paradigm shift is an important factor, expanding the repertoire of recorded music, changing the business model of the music industry itself, and liberating creative instincts that previously had been “damped by dollar signs.”

Big-name artists engage in elaborate tours, spanning the globe in some cases. They became popular through recordings created in studios, and reconstructing the essence of that recorded “sound” in a concert situation is sometimes a goal. Occasionally, excerpts of studio recordings creep into the live performances. None of this is a problem because it was always an artificial creation, owing little or nothing to any live unamplified performance. It might seem like cheating, but there are some effects that cannot be duplicated in live performances. In the end, the delivered “art” is what matters.

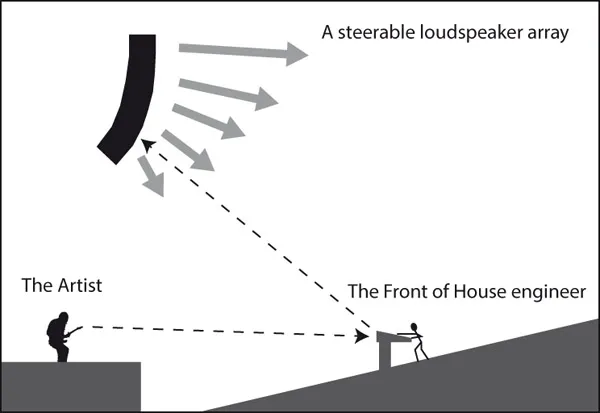

Figure 1.2 shows that in live, amplified/sound reinforced, popular music performances, the front-of-house (FOH) engineer is in control of the performance heard by the audience. It is an artistic creation in real time, and can vary enormously with different engineers, their tastes and, interestingly enough, how well they hear. I left one show at intermission because the sound was far too loud, and not very good. I learned later that the FOH engineer was known by insiders to have serious hearing loss, but had a long relationship with the performer. Pity. This is a situation in which, for a variety of acoustical, technical and personal reasons, live popular music performances are variable.

One can correctly assert that a live popular music performance is what it is at the time, and may never be repeated again. It is sound production.

Figure 1.2A functional diagram of a tour sound system. The microphone and direct-wired inputs from the artists on stage are mixed and manipulated by the front-of-house (FOH) engineer, based on what is heard from the loudspeaker array, the sound of which is shared with the audience.

1.3 Reproduced Sound—The Audio Industry

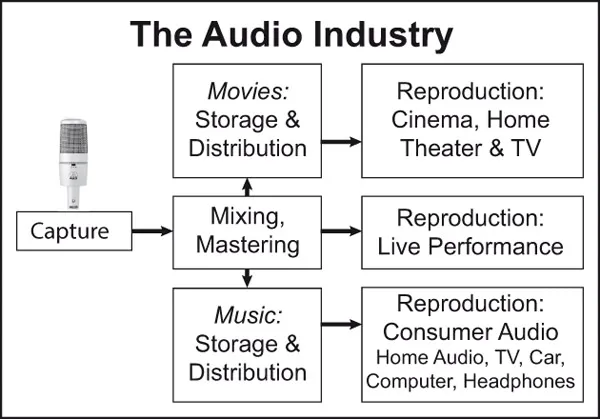

Sound reproduction is different. At some time and place, an original performance occurs, and the objective is to reproduce that performance with as much accuracy as possible whenever and wherever someone chooses to press a “play” button. Most of our listening experiences involve recordings, broadcasts or streaming audio that is reproduced through loudspeakers in a room, loudspeakers in a car or through headphones. This is the audio industry, as shown in Figure 1.3.

Clearly the audio industry is a complex operation, requiring extensive standardization if all of the devices within these different operations and business units are to be compatible with the signals moving through them. More importantly, there is the matter of what listeners in these varied situations hear. Is the result of the mixing and mastering engineering accurately delivered to the customers’ ears?

A fallacy: That reference to a “live” sound is the only way to judge sound quality. Reason: microphones capture only a sample of the live sound field that we would hear in a live performance. Parts are missing. Recording engineers can manipulate the mix to sound something like the live sound, to create a totally artificial experience or anything in between.

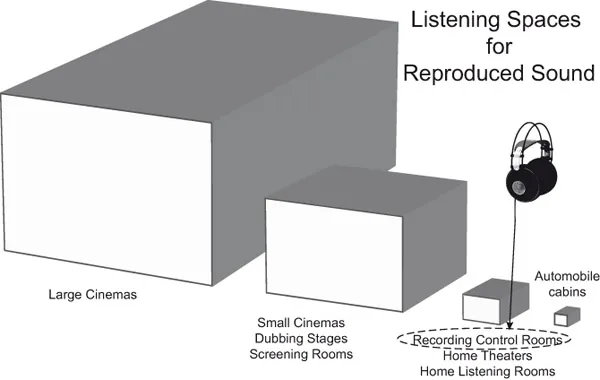

Figure 1.4 illustrates the enormous contrasts in scale involved in reproduced sound, and it is reasonable to think that the differences might be insurmountable. Can movies created for large cinemas be credible in small home theaters or television sets in tiny apartments? The delivery systems, the film and music formats also differ, and new options continue to evolve. Making it all work involves complex engineering of many kinds, and some of it requires research to optimize the processes that deliver sounds to listeners’ ears, making them appropriate for the circumstances.

Figure 1.3The audio industry as we know it.

Figure 1.4The range of listening spaces within which accurate sound reproduction is desired.

Fortunately, cinemas are designed to have reverberation times that are not very different from domestic rooms. Combined with the large directional loudspeakers normally used, listeners end up in fundamentally similar sound fields and the experiences are acoustically more similar than might have been expected. This is discussed in detail later on.

Headphones normally replay stereo sound tracks created using loudspeakers in recording control rooms. Although it is possible to achieve a good timbral match, the spatial presentation is fundamentally different from that delivered by loudspeakers, sounds being localized primarily within or close to the head. For optimum headphone experiences, binaural (dummy head) recordings are needed, but we seem to have adapted well to the gross spatial distortions commonly experienced. The music survives.

The portrayal in Figure 1.5 could very well be wrong in detail, but there is little doubt that the trend is correct. The circumstances within which we are primarily entertain...