eBook - ePub

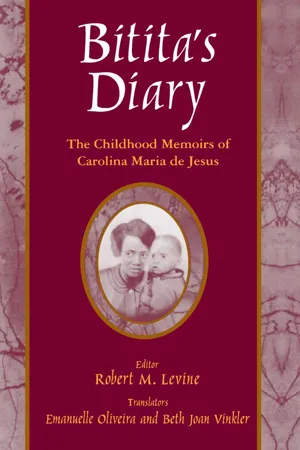

Bitita's Diary: The Autobiography of Carolina Maria de Jesus

The Autobiography of Carolina Maria de Jesus

This is a test

- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bitita's Diary: The Autobiography of Carolina Maria de Jesus

The Autobiography of Carolina Maria de Jesus

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Carolina Maria de Jesus (1914-1977), nicknamed Bitita, was a destitute black Brazilian woman born in the rural interior who migrated to the industrial city of Sao Paulo. This is her autobiography, which includes details about her experiences of race relations and sexual intimidation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Bitita's Diary: The Autobiography of Carolina Maria de Jesus by Carolina Maria De Jesus,Robert M. Levine,Beth Joan Vinkler,Emanuelle Oliveira in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

________________________

Childhood

The poor lived on a plot of state land, named the “Heritage.”

There was no running water. Even with the well, they had to walk to transport the water. We lived on land that Grandpa bought from a man known as the “teacher,” who owned a private school. The price of the land was fifty thousand réis.1 Grandpa said that he did not want to die and leave his children homeless.

Our little home had a thatch roof. The walls were made of adobe covered with straw. Every year we had to change the straw, because it would rot and had to be changed before the rains came. My mother paid ten thousand réis for a cartload of straw. The floor was not made of wood, it was earth, made hard over time by many steps.

I was making my avant-première2 in the world. I knew my brother’s father, and I didn’t know my own. Does every child have to have a father? My mother’s father was Benedito José da Silva, his last name was the master’s. He was a tall, peaceful black man, resigned to his fate as a pawn of slavery. He did not know how to read, but he spoke with a soft, pleasant voice. He was the most handsome black man I have ever seen in my life.

I thought it was so beautiful to hear my mother say, “Papa!” and my Grandpa’s response, “What is it, my dear?” I envied my mother because she knew both her father and mother.

I often thought about asking her who my father was, but I didn’t have the nerve. I thought it was disrespectful to ask such a question. To me, the most important people were my mother and my grandfather.

I heard the old women say that children must obey and respect their parents. One day, I heard from my mother that my father was from Araxá and that his name was João Cândido Veloso. My grandmother’s name was Joana Veloso. My father played the guitar, and he didn’t like to work. He only had one pair of clothes, when my mother washed his clothes, he would lay down naked. He waited for his clothes to dry to get dressed and go out. I came to the conclusion that we never have to ask anyone anything. With time we will come to know all.

Whenever my mother talked, I would get close so I could listen to her. One day, she scolded me and said, “I don’t like you!” I answered her, “I’m only in this world because of you. If you hadn’t been with my father I wouldn’t be here.” She smiled and said, “What an intelligent girl! And she’s only four!” My aunt Claudimira said, “She’s rude!” My mother defended me, saying that what I said was true. “She needs to be spanked. You don’t know how to raise children.” They started to argue and I thought, “My mother was the one who was insulted, but she isn’t hurt.” I realized my mother was the more intelligent one.

“Spank her! Spank the little black girl! She’s only four, but as the twig is bent, so grows the tree.”

“People are born what they are, they don’t change!” answered my mother.

I became worried, thinking. What can “four” mean? Can it be a sickness? Can it be a treat? I went running off when I heard my brother’s voice calling me to pick garibolas.3

Saturdays really worried me. What excitement! Men and women were getting ready to go to the dance. Can a dance be essential to people’s lives? I asked my mother to take me to the dance. I wanted to see what a dance was, to see what caused such excitement among the blacks. They talked about the dance over a hundred times a day …

A dance … It must be something really good, because people who talked about it always smiled. But the dance was at night, and at night I was sleepy.

I envied the women. I wanted to grow up and get a boyfriend. One day, I saw two women fighting over a man. They said, “He’s mine, tramp! Bitch! Slut! If I find out you slept with him, I’ll kill you!” I was shocked. Can a man be such a good thing? Why should women fight over them? So, men are better than coconut candy, peanut brittle, french fries with a steak? Why should women want to get married? Can a man be better than fried bananas with cinnamon and sugar? Can a man be tastier than rice with beans and chicken? Will I get a man when I grow up? I want a very handsome man!

My ideas changed from minute to minute, just like the clouds in the sky that make beautiful scenes. After all, if the sky were always clear blue, it wouldn’t be so lovely.

One day I asked my mother, “Mama, am I a person or an animal?”

“You’re a person, dear!”

“What does it mean, to be a person?”

My mother didn’t answer. At night, I looked at the sky. I watched the stars and wondered, “Can it be that stars talk?” “Do they dance on Saturdays? On Saturday I will look to see if they are dancing. In the sky there must be women-stars and men-stars. Can it be that the women-stars fight over the men-stars? Can the sky be only where I am looking?”

When I went with my mother to get firewood, I saw the same sky.

In the woods, I saw a man cut down a tree. I was envious and I decided to be a man so I could be strong. I looked for my mother and begged her, “Mama, I wanna be a man. I don’t like being a woman! Come on, Mama! Change me into a man!” When I wanted something, I could cry for hours and hours.

“Go to bed. Tomorrow, when you wake up, you will be a man.”

“How great! How great!” I exclaimed, smiling.

When I become a man, I will buy an ax and chop down a tree. Smiling and bursting with happiness, I imagined I would need to buy a razor to shave and a rope to tie up my pants. I’d buy a horse, spurs, a broad-brimmed hat, and a whip. I intended to be an upright man. I wasn’t going to drink pinga.4 I wouldn’t steal, because I don’t like thieves.

I lay down and went to sleep. When I woke up, I went looking for my mother and cried, “I didn’t turn into man! You fooled me!” I raised my dress so she could see I was still a girl. I followed her around, crying and begging, “I wanna be a man! I wanna be a man! I wanna be a man!” I kept it up all day long. The neighbors got impatient, “Dona5 Cota, spank this little black girl! What a pain this girl is! What a monkey!” But my mother indulged me and said, “When you see a rainbow, you run under it. Then you will become a man.”

“I don’t know what a rainbow is, Mama!”

“A rainbow is an arco-da-velha.”6

“Oh!”

And my gaze turned to the sky. That being the case, I would have to wait until it rained, and then the rainbow would appear. I quit crying for a few days. One night, it rained. I got up to see if I could find the rainbow. My mother came to see what I was doing. Seeing me look at the sky, she asked, “What are you looking for?”

“The rainbow, Mama.”

“Rainbows don’t come out at night.”

My mother didn’t talk much.

“Why do you want to be a man?”

“I wanna be as strong as a man. A man can chop down a tree with an ax. I wanna have a man’s courage. He walks in the woods and isn’t afraid of snakes. A working man makes more money than a woman, and gets rich and can buy a beautiful house to live in.”

My mother smiled and took me back to bed. But when she got tired of my questions, she would beat me.

My baptismal godmother7 defended me. She was white. When she bought a dress for herself, she would buy another for me. She combed my hair and kissed me. I thought I was important because my godmother was white.

I only wanted to eat delicious things. I remember that when I ate fried bananas with cinnamon, I said, “How tasty!” And for several days, I thought of nothing but fried bananas with cinnamon. If only I could eat a little bit more! If only I could eat that again!

I ate canned coconut candy. Oh, how delicious! And I could only think about canned coconut candy. The first time that I saw canned sardines and ate them with bread … Poor Mama! I didn’t give her a break. I kept asking her, “I want that tasty thing! I want that tasty thing!” And I followed my mother all around.

My aunt Teresa asked, “What does she want?”

I heard my mother say, “She wants sardines with bread.”

And that’s how I learned that those tasty things were sardines.

I was unbearable. When I wanted something, I cried night and day until I got it. I was very persistent in all of my whims. I thought the most important thing was to get what you wanted. And my wishes were satisfied. The only way my mother could live in peace was to give in to me. She was tolerant. She looked at me, smiled, and said, “Look at her face!” She didn’t beat me.

The neighbors looked at me and said, “What an ugly little black girl! She’s not only ugly, she’s nasty! If I were her mother, I would have killed her already !” My mother looked at me and said, “A mother doesn’t kill her child. What a mother needs is lots of patience! Mr. Euripedes Barsanulfo told me she was a poet!”

1. The réis is an old Brazilian monetary unit which was replaced by the cruzeiro in 1942. One conto de réis was equal to U.S.$107 in 1930, so that fifty thousand réis, the price Carolina says her grandfather paid for the house, would have been $5,350 in 1930 U.S. dollars. She was probably wrong because this price would have been too high for someone as poor as her grandfather.

2. Avant-première, premiere, as in the premiere of a play. Carolina uses the French.

3. Garibolas are a regional fruit.

4. A strong alcoholic drink made of fermented sugar cane.

5. Dona is a term of respect roughly equivalent to “ma’am.”

6. According to the Novo Dicionário Aurélio da Língua Portuguesa, 2nd edition, an arco-da-velha is a colloquial term for rainbow. There is a Brazilian saying, “Ela fez coisas do arco-da-velha,” meaning “She did extraordinary things.” Thus, one can relate the arc of the rainbow with extraordinary occurrences.

7. In Brazilian culture, the godparent relationship is an important one. People chose different godparents for the various events in their lives: baptism, first communion, marriage. The popular terms compadre, for men,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Latin

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Series Foreword by Robert M. Levine

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction by Robert M. Levine

- 1. Childhood

- 2. The Godmothers

- 3. The Holiday

- 4. Being Poor

- 5. A Little History

- 6. The Blacks

- 7. My Family

- 8. The City

- 9. My Son-in-Law

- 10. Grandfather's Death

- 11. School

- 12. The Farm

- 13. I Return to the City

- 14. The Domestic

- 15. Illness

- 16. The Revolution

- 17. The Rules of Hospitality

- 18. Culture

- 19. The Safe

- 20. The Medium

- 21. The Mistress

- 22. Being a Cook

- Afterword

- About the Editor