Slavery Takes Root in Early America

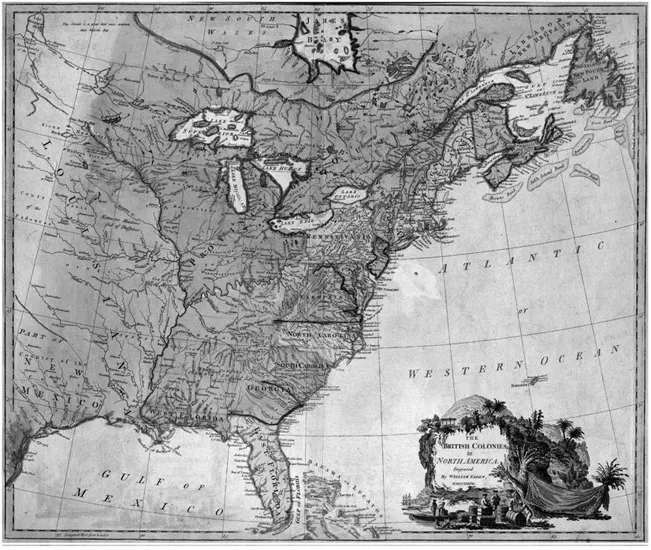

Imagine the thoughts of English colonists who undertook the treacherous journey across the Atlantic to settle in the New World. They had risked their lives to venture to a mysterious land only dimly understood. Maps only vaguely represented the New World, and vast stretches of the North American continent remained terra incognita, shrouded in obscurity. Along the Atlantic Coast of North America hundreds of Native American tribes, vast acres of virgin forests, and innumerable species of native birds and other game filled the landscape. It was a land at once promising and scary.

When English colonists set foot in the Americas in the early 1600s, they found an abundance of land available for growing cash crops. Though it took them a few years to realize it, tobacco in particular would become vital to the economy of colonial America. The first permanent English colony, Jamestown, was founded in 1607 but from the beginning there were relatively few white colonists to exploit the tens of thousands of acres of potentially cultivatable land. Even a significant increase of British immigrants to the New World in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries failed to provide sufficient numbers of colonists for agricultural labor.

Figure 1.1 The settlement of Jamestown in 1607. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, 808025

Almost as soon as the Jamestown colony was settled, large farms called plantations began to emerge along the rivers of Virginia and Maryland, known together as the Chesapeake region. The crops grown in the colonial South, especially rice, cotton, tobacco, and indigo (a plant used for making dye), were very labor-intensive, meaning that they required hours of daily toil in harsh conditions. Despite the widespread use of the indenture system, labor in the colonial South remained scarce; there were simply not enough people to do all of the necessary agricultural work.

In the search for more laborers, Native Americans were among the first to be enslaved. In Jamestown’s early years, relationships between the English colonists and Native Americans like the Powhatan tribe alternated between peace and warfare. By the 1630s the Chesapeake colonists maintained a consistently brutal policy toward the Native Americans in their midst, including capturing men, women, and children and forcing them to work as slaves. According to historian Alan Gallay, between 30,000 and 50,000 Indians had been enslaved by the early 1700s in North America. But because of a high death rate and susceptibility to disease, Native American slaves could not fill the labor needs of the colonies. In addition, Indian men often refused to do agricultural labor, which they considered to be “women’s work,” and because the Indians knew the land much better, and knew how to survive in the wilderness, they could escape easily and make their way back to their villages. In the end, although the Indian slave trade persisted in the English colonies into the eighteenth century, Indian slave labor proved impractical.

Colonial leaders and planters turned to indentured servitude to help solve the initial labor shortage. Under this system, poor whites in England (usually men but sometimes women) would enter into a contract with an employer in the colonies who offered transatlantic passage in exchange for a predetermined number of years in labor. Contracts varied from four to seven years but, whatever the length of the contract, the servant was bound to the employer. Indentured servants were more than slaves; there were laws that protected them from bodily harm, although colonial authorities were not always very responsive to abuses. But they were similar to slaves in that they were not free; they needed passes, or legal documents, when traveling, and essentially were the property of their masters for the length of the contract. Finally, masters could sell their servants for the remaining terms of their contracts whenever they pleased. In general all these changes moved the institution of colonial servitude closer to a system of slave labor in which workers were considered property and their labor traded and sold. Indentured servitude, then, was something of a halfway point between free and slave labor.

Map 1.1 The British colonies in North America. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, 484202

At the same time, colonial farmers and planters turned to the African slave trade to fill their labor needs. Beginning in the 1670s, slaves imported from Africa became a dominant feature of the colonial American economy, especially in the South. The English colonists who came to settle in the southern colonies found that land was abundant and relatively easy to obtain. The first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, but the black population was slow to rise until the 1660s and 1670s. Only 300 to 400 Africans lived in the Chesapeake colonies in 1650, a mere 2% of the population. Even in 1670, the black population was only 5%. But by 1700, Africans or those of African descent comprised 35% of the total number of those living in the Chesapeake colonies.

Between 1675 and 1700, there were many reasons why the colonists saw black slavery as a more attractive labor system than white servitude. First, indentured servitude was only temporary; this practice meant that each year a new group of servants who had completed their contracts became a burden on colonial society. As Edmund S. Morgan argued in his important book American Slavery, American Freedom, Bacon’s Rebellion, which saw blacks and poor whites banding together to fight authority, demonstrated to colonial leaders the dangers of importing more indentured servants. Usually servants ended their contracts with no money, no shelter, few skills, and only the clothes on their backs. Colonial elites in the South became concerned about the potential political hazard posed by the abundance of former servants. Second, changes in immigration meant that by the mid- to late 1600s, as economic conditions slowly improved in England, fewer white servants wanted to migrate. In addition, as life expectancy for all races rose in the Chesapeake in the 1600s, slaves became a better investment. Slaves were more expensive than indentured servants, but as the likelihood of slaves living longer increased, their high cost was more justified. Colonial laws, such as a Maryland statute explicitly stating that the children of slave mothers would also be slaves, ensured that bondage would pass from one generation to the next; this doctrine was never applied to white indentured servants, only to black slaves. Finally, racial prejudice, especially long-held beliefs about African inferiority, spurred the growth of the slave trade. Winthrop D. Jordan and other historians have underscored long-standing white European beliefs that God destined Africans and other dark-skinned peoples for hard, physically demanding labor.

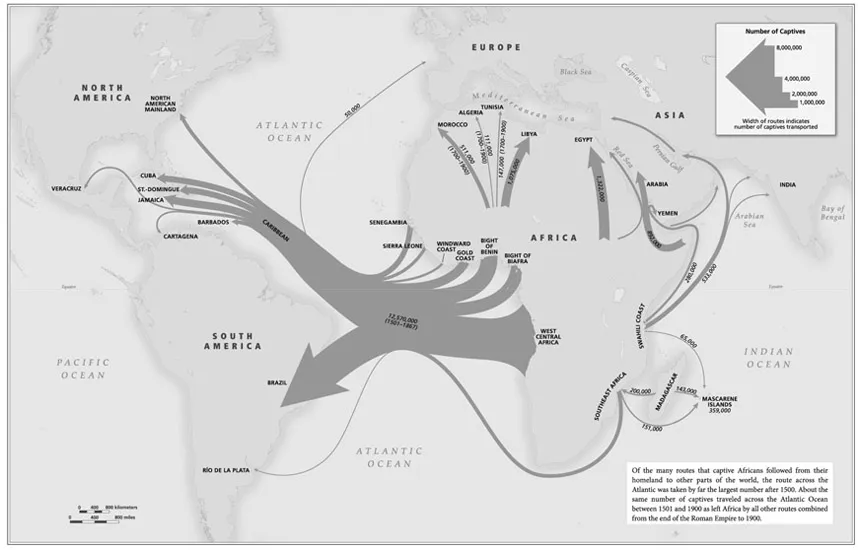

Only about 5% of all Africans that were brought to the New World went to the English colonies along the Atlantic Coast of North America; the vast majority went to Brazil, the Caribbean, and other Latin American colonies. Slavery took root as well in the northern colonies, and New York City would remain an important center of slavery throughout much of the colonial era. Slaves in the northern colonies not only worked on farms, but also helped load ships in port towns, worked as artisan laborers in carpentry, iron-forging, masonry, and other skilled crafts, and worked in physically demanding jobs such as digging trenches.

Those slaves who did come to the English colonies were sold mostly in the South. The rocky soil in New England was not as useful for growing crops like tobacco. Tobacco required much work, as did other crops that dominated the South, such as indigo, rice, sugar, and later cotton. These crops required many hours in the sun, sometimes in swampy conditions infested with mosquitoes and other pests. The English believed that Africans were better suited to these kinds of working conditions. As one white woman, Louisa McCord of South Carolina, put it: “The white man will never raise, can never raise, a cotton or a sugar crop in the United States. In our swamps and under our suns the negro thrives, but the white man dies.” Employing such rationalizations, colonial racism made the expansion of African slavery possible and ensured that slavery would play a central role in the nation’s founding. However, some religious groups in the northern colonies thought slavery was immoral. Quakers in Pennsylvania, for example, remained largely opposed to bondage before and after American won independence from Britain.

Map 1.2 Overview of the slave trade out of Africa, 1500–1900. David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 2010

Rise of the Slave Trade

The African slave trade is one of the darkest stories in human history. The ruthlessness with which men and women of all ages were forcibly transported to the New World is stunning. Yet the slave trade did not begin with the opening of the Americas in the 1600s. Europeans had owned slaves (both white and black) long before the beginning of American colonization. In ancient civilizations in Egypt, Greece, and Rome, slavery was an important part of the economy and society. Africans themselves had been active for hundreds of years in capturing other Africans and selling them into slavery. But slavery meant different things at different times, and scholars have discovered that the concept of slavery is a complicated one. If you are used to thinking of slaves as agricultural laborers, you might be surprised to find that in world history, slaves were often soldiers, government officials, wives, concubines, and tutors, and that some societies even allowed their slaves to participate in politics.

Despite the long and sad history of human slavery, bondage seemed particularly brutal in the New World. The first colonists and traders to bring Africans to the Americas were the Spanish and Portuguese, who used them to replace or supplement the dwindling numbers of Indian slaves toiling in Caribbean colonies. Large plantations, some with thousands of slaves, grew sugar and other crops. Jamaica, Haiti, Cuba, Bermuda, and other islands were the centers of the slave trade in the New World. Slavery in the Caribbean was brutal, with punishments swift and harsh on large sugar plantations or in mining operations. Tens of thousands of slaves also went to South America, particularly Brazil, which in the 1880s became the last country in the western Hemisphere to outlaw slavery. In fact, after the South lost the Civil War many southerners moved to Brazil, carrying their slaves with them, and reestablished their plantations where a community of descendants from the American South lives to this day. Slavery, therefore, was not confined to the colonial South; it was a worldwide practice that had involved many of the world’s leading nations, and had spread to the New World particularly rapidly.

How did Africans get to the New World? With the permission of local African rulers, Europeans built forts and trading posts on the West African Coast and bought slaves from African traders. African rulers also occasionally enslaved and sold their own people as punishment for crimes or for being in debt; others enslaved fellow Africans as prisoners of war. Attracted by European cloth, iron, liquor, guns, and other goods, West Africans fought increasingly among themselves to secure captives and began sending raiding parties to kidnap individuals from the interior. This trade created a snowball effect whereby one tribe would receive metal products, food, and weapons in exchange for slaves. The tribe would then become stronger, enabling it to push into the interior of Africa, conquering even more tribes in a vicious cycle.

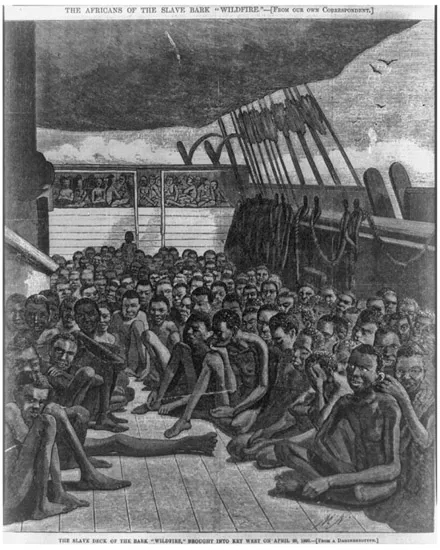

Figure 1.2 Enslaved Africans on board a slave ship. Library of Congress, Images of African-American Slavery and Freedom, LC-USZ62-41678

Slaves who survived the ordeal of transportation to the trading forts on the coast faced an almost unimaginable ordeal on the ships to the colonies, a six- to eight-week-long forced migration that has come to be called the “Middle Passage.” Captains wedged men below the decks into spaces about six feet long, sixteen inches wide, and thirty inches high. Slaves were often packed so tightly that they could barely move. Women and children were packed even tighter than men. Slaves were sometimes allowed on deck for fresh air, but most of the time they remained below the decks, where the hot and humid air grew foul from the vomit, blood, and excrement in which they were forced to lie. Some slaves nearly went insane; others tried to commit suicide by starving themselves or jumping overboard to drown. On many voyages, scores of enslaved people died from disease, but captains figured this into their calculations for profit and packed enough slaves in the ship to make money.

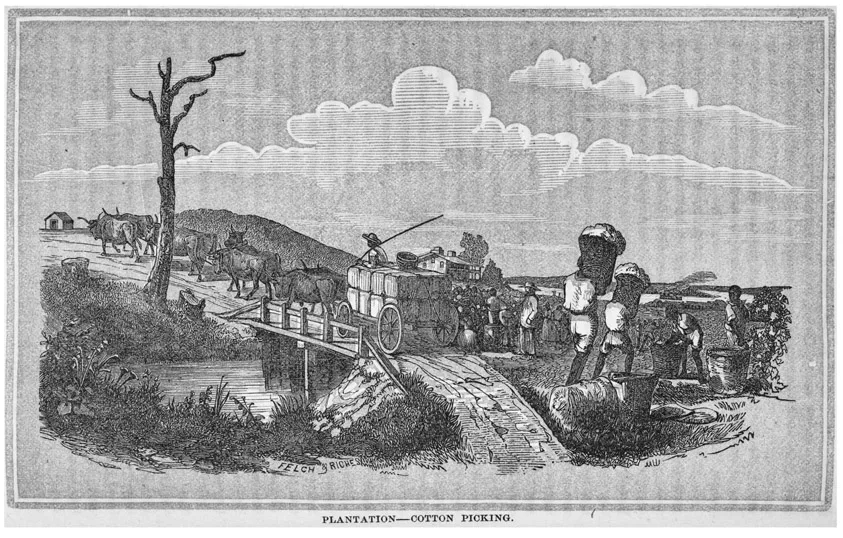

Figure 1.3 Plantation—cotton picking. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, 427779

Those enslaved men and women who survived the kidnapping from their homelands then had to endure the fear and humiliation of being sold. Historian Walter Johnson has found that in slave markets, such as those in New Orleans, slaves were subjected to close and demeaning inspection by speculators who often abused female slaves. For abolitionists who wanted to end slavery, the slave trade was the worst feature of bondage. In fact, many northerners were abolitionists based solely on their opposition to the buying and selling of human beings. Southern port towns such as Wilmington, Savannah, Charleston, and New Orleans boasted active slave markets, and traders and speculators often purchased slaves in the older states like Virginia and South Carolina only to sell them in the booming southwestern states like Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas. Sometimes slaves were purchased right off the ships, and sometimes a public auction was held. In the “scrambles,” potential buyers rushed on bo...