eBook - ePub

Energy for the 21st Century

A Comprehensive Guide to Conventional and Alternative Sources

This is a test

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Energy for the 21st Century

A Comprehensive Guide to Conventional and Alternative Sources

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A compendium of current knowledge about conventional and alternative sources of energy. It clarifies complex technical issues, enlivens history, and illuminates the policy dilemmas we face today. This revised edition includes new material on biofuels, an expanded section on sustainability and sustainable energy, and updated figures and tables throughout. There are also online instructor materials for those professors who adopt the book for classroom use.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Energy for the 21st Century by Roy Nersesian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

____________________________________

____________________________________

ARE WE ON EASTER ISLAND?

Energy is a natural resource and, for the most part, finite. Exhaustion of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) is not imminent, although we may be at the onset of negotiating a slippery slope with regard to oil production. Interestingly, we have a history of responding to finite natural resources in danger of exhaustion. We exhausted forests in Europe at the start of the Industrial Age in our quest for making glass and metals, and we nearly drove whales to the point of extinction during the nineteenth century in our quest for whale oil. Fortunately, we found ways to avert what could have been a terminal crisis. The forests in Europe were saved from the axe by the discovery of coal as an alternative to wood in glass- and metal-making. Whales were saved from extinction by finding an alternative source for their oil for lighting in the form of kerosene. In the twentieth century we took effective action to rejuvenate a threatened species of marine animal life, but at the same time we discovered the technology to strip-mine the open oceans of fish life. As we exhaust open-ocean fishing, an alternative has been found in aquaculture or fish farming. Aquaculture is similar to relying on sustainable biofuels whereas open-ocean fishing, when fish are caught faster than they can reproduce, is similar to exhausting fossil fuels.

In the case of energy, it is true that immense energy reserves have been found that have kept up with our horrific appetite for energy, making mincemeat of Theodore Roosevelt’s prediction, from the vantage point of the early twentieth century, that we will soon exhaust our natural resources. A key question facing us is whether the future pace of discovery can keep ahead of our growing appetite for energy; that is, will Roosevelt ultimately be proven right? Just because we run short of a natural resource does not necessarily mean that we can find an alternative. That is the tragedy of Easter Island.

EASTER ISLAND

Easter Island is over 2,000 miles from Tahiti and Chile. To the original inhabitants, Easter Island was an isolated island of finite resources surrounded by a seemingly infinite ocean. What happened on Easter Island when it ultimately exhausted its finite resources is pertinent because Earth is an isolated planet of finite resources surrounded by seemingly infinite space. Whether we admit it or not, we are in danger of exhausting our natural resources. Rough, and some deem optimistic, estimates are forty years for oil, sixty years for natural gas, and a one hundred twenty years for coal. These are not particularly comforting when viewed from the perspective of a six thousand year history of civilization. Like the Easter Islanders who had nowhere to go, this is our home planet now and for the foreseeable future. Space travel is a long way off, and flying off to Mars to escape a manmade calamity on Earth is not a particularly inviting prospect.

Examination of the soil layers on Easter Island, or Rapa Nui to the present inhabitants, reveals an island with abundant plant and animal life that existed for tens of thousands of years. Around 400 CE, the island was discovered and settled by Polynesians, who originally named the island Te Pito O Te Henua (Navel of the World). The natives survived on the bounty of natural animal and plant life on the island and fish in the surrounding waters. Critical for survival was the eighty-foot tall Easter Island palm that provided sap and nuts for human consumption and canoes for fishing. The palms also provided the means to move the massive stone Moai, stone figures for which the island is famous, which now stand in mute testimony to an ecological catastrophe that unfolded around 1500. By then, the estimated population had grown to somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 inhabitants.

This sounds like an awful lot of people descended from a few settlers, but this is the nature of exponential growth. If a party of ten people originally settled on Easter Island and grew at a relatively modest 1 percent per year (about the current growth rate in world population), the number of Easter Islanders would double about every seventy years. There were nearly sixteen doublings of the population in the 1,100 years from 400 to 1500 CE. Double ten sixteen times and see what you get. In theory the population would have grown to 567,000, a mathematical consequence of compound exponential growth at 1 percent per year over 1, 100 years. It would never have reached this level because, as proven in 1500, a population in excess of 10,000 was sufficient to exhaust the island’s natural resources.

A growing population increased the demand for meat, which eventually led to the natives feasting on the last animal. More people and no animals promoted more intensive tilling of the land, which first had to be cleared of the palms. With fewer palms, erosion increased and, coupled with the pressure to grow more crops, soil fertility declined. Of course the palms did not go to waste as they were needed to support the leading industry on Easter Island: the construction and moving of the Moai, plus of course, canoes. Fish became more important in the diet as the population grew, the animals disappeared, and crop yields fell. Around 1500, the last palm tree was cut down. Bloody intertribal warfare, cannibalism, and starvation marked the demise of a civilization.

On Easter of 1722, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen rediscovered the island. It presented a great mystery, as the few surviving and utterly impoverished natives had no memory of the tragedy nor did they understand the meaning of the Moai. The gift of Western civilization—infectious disease—ultimately reduced the native population to a remnant of 111 by 1800. In 1888, when the island was annexed by Chile and renamed Rapa Nui, the population had risen to 2,000 (a growth rate considerably in excess of 1 percent!).

THE MATHEMATICS OF EXTINCTION

Suppose that we depend on a forest for supplying wood for fuel and building material. If the forest grows at 3 percent per year and we remove 2 percent of the forest per year, the resource will last forever (a sustainable resource). The forest also lasts forever if 3 percent is removed per year, but care has to be exercised to ensure that removal does not exceed 3 percent. If consumption exceeds 3 percent as a consequence of a growing population that needs more wood for fuel and shelter, or if a new technology is introduced that consumes a great deal of wood, such as glass- and metal-making, then the forest will eventually be consumed (a nonsustainable resource).

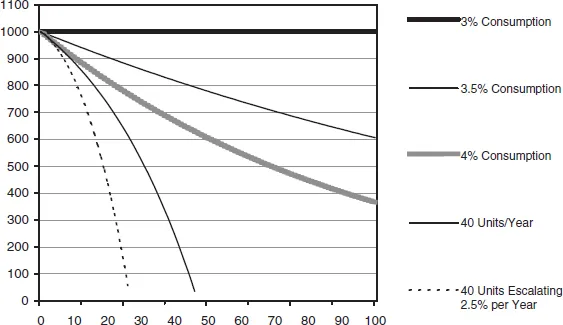

Suppose that a forest consists of 1,000 units of usable wood that increases naturally by 3 percent per year. Figure 1.1 shows what happens to the forest as a resource in terms of units of usable wood when consumption is 3, 3.5, and 4 percent per year. While the forest is a sustainable resource if consumption is limited to 3 percent, in a century the forest will be reduced to 600 and 380 units for consumption rates of 3.5 and 4 percent respectively. One hundred years in the recorded 6,000-year history of humanity is not very long; for a growing minority, it is a single lifetime. But this does not accurately describe the situation. What is wrong with this projection is that demand declines in absolute terms over time. For example, in the first year the forest gains 30 units and consumption at 4 percent is 40 units, leaving 990 units for the next year. When the forest is down to 800 units, consumption at 4 percent has been reduced from 40 to 32 units.

Figure 1.1 Exhausting a Natural Resource

This is notrealistic; there is no reason for demand to decline simply because supply is dwindling. Suppose that consumption remains constant at 40 units with 3 percent growth in forest reserves. Then, as Figure 1.1 shows, the forest is transformed to barren land in 47 years. The final curve is the most realistic. It shows what would happen if consumption climbs at 1 unit per year; 40 units in the first year, 41 units the second, and so on, which is reflective of a growing population. Now the forest is gone in 30 years, a single generation.

Yet, even this projection is not realistic. Consumption, initially growing by 1 unit a year, declines in relative terms over time. For instance, when consumption increases from 40 to 41 units, growth is 2.5 percent; from 50 to 51 units, growth has declined to 2 percent. Another curve could be constructed holding consumption growth at 2.5 percent, based on a starting point of 40 units per year. But the point has already been made: The resource is exhausted within a single generation.

Before the resource is exhausted, other mitigating factors come into play. One is price, a factor not at play on Easter Island. As the forest diminishes in size and consumers and suppliers realize that wood supplies are becoming increasingly scarce, price would increase. The more serious the situation becomes, the higher the price. Higher prices dampen demand and act as an incentive to search for other forests or alternative sources for wood such as coal for energy and plastic for wood products (neither option available to the Easter Islanders).

Price would certainly have caused a change of some sort to deal with the oncoming crisis, but would not have affected the eventual outcome. A very high price for the last Easter Island palm would not have saved a civilization from extinction. The individual who became rich selling the last palm would have to spend his last dime buying the last fish. Easter Island is not the only civilization that collapsed from a shortage of natural resources. It is believed that the fall in agricultural output from a prolonged drought caused the demise of the Mayan civilization in Central America. Ruins of dead civilizations litter the earth, a humbling reminder of their impermanence.

PROGRESS IS OUR MOST IMPORTANT PRODUCT

About one-third of the earth’s population still depends on wood as a primary energy source. Unfortunately, removing forests to clear land for agriculture is often considered a mark of progress. Where cleared land stopped and forests began marked the boundaries of the Roman Empire. Agriculture transformed war-loving hunter-gatherers into law-abiding agrarians. The resuscitation of civilization during the Middle Ages was evidenced by forests and abandoned lands transformed to vineyards and other forms of agricultural enterprise by monks. Removal of forests to support a growing population became too much of a good thing. The first energy crisis occurred early in the Industrial Revolution when wood demand for housing, heating, and the new industries of glass- and metal-making exhausted a natural resource. A crisis turning into a calamity was averted by the discovery of coal in England and forests in North America.

The growth of the United States as a nation can be traced by the clearing of a large portion of the forest covering the eastern half of the nation for farmland. This was a visual sign of progress for pioneers seeking a new life in the Americas. Despite environment protestations to the contrary, clearing forests is still considered a sign of progress. We are intentionally burning down and clearing huge portions of the rain forests in the Amazon and in Southeast Asia for cattle grazing and other forms of agriculture.

Burning wood or biomass faster than it can be replaced by natural growth adds carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) releases carbon dioxide previously removed from the atmosphere by plant, animal, and marine life millions of years ago. The increasing concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is blamed on both the continuing clearing of forests and our growing reliance on fossil fuels. At the same time, clearing forests and consuming energy are signs of economic progress to raise living standards. Although there is intense public pressure to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, over half of the planet’s population live in nations in South America and Asia where governments have been active in increasing carbon dioxide emissions in pursuit of economic development. However, in recent years, concerns have been raised on the effect of water and air pollution on the health of the people and efforts are being initiated to curb pollution.

Unlike the unhappy experience of the Easter Islanders, there are countervailing measures being taken to compensate for burning down vast tracts of the world’s tropical forests. Tree farms and replanting previously harvested forests ensure a supply of raw materials for lumber and paper-making industries for their long-term sustainability. A number of public service organizations are dedicated to planting trees to combat the rising concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. An increasing carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere itself promotes plant growth that would be a natural countermeasure (an example of a negative feedback system). Yet despite human efforts to the contrary, the world’s resource of forests continues to dwindle and the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere continues to climb.

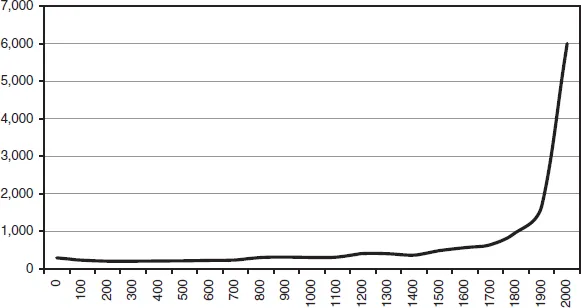

THE UNREMITTING RISE IN POPULATION

Both energy usage and pollution can be linked directly to population. Indeed, there are groups who advocate population reduction as the primary countermeasure to cut pollution of the land, air, and water. These groups have identified the true culprit of energy exhaustion and environmental pollution, but their suggested means of correcting the problem does not make for comfortable reading. Figure 1.2 shows the world population since the beginning of the Christian era and its phenomenal growth since the Industrial Revolution.1

Figure 1.2 World Population

The world’s population was remarkably stable up to 1000 CE. The Dark Age of political disorder and economic collapse following the fall of the Roman Empire around 400 CE was instrumental in suppressing population growth. The high death rate for infants and children and the short, dirty, brutish lives of those who survived childhood, coupled with the disintegration of society, prevented runaway population growth. After the Dark Age was over, the population began to grow accompanied by a period of global warming. This continued until the Black Death starting around 1350, which occurred during a period of global cooling. With several recursions over the next hundred years, the Black Death wiped out massive numbers of people in Asia and Europe. More than one-third of Europe’s population were victims, with as much as two-thirds in certain areas. It took over a ce...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- 1 Are We on Easter Island?

- 2 Electricity and the Utility Industry

- 3 Biomass

- 4 Coal

- 5 The Story of Big Oil

- 6 Oil

- 7 Natural Gas

- 8 Nuclear and Hydropower

- 9 Sustainable Energy

- 10 Looking Toward the Future

- 11 An Energy Strategy

- Index

- About the Author