![]()

1 Introduction to cost-benefit analysis

1.1 Introduction

Cost-benefit analysis is a process of identifying, measuring and comparing the benefits and costs of an investment project or program. A program is a series of projects undertaken over a period of time with a particular objective in view. A project is a proposed course of action that involves reallocating productive resources from their current use in order to undertake the project. The project or projects in question may be public projects – projects undertaken by the public sector – or private projects. Both types of projects need to be appraised to determine whether they represent an efficient use of resources. Projects that represent an efficient use of resources from a private viewpoint may involve costs and benefits to a wider range of individuals than their private owners. For example, a private project may pay taxes, provide employment for some who would otherwise be unemployed, and generate pollution. The complete set of project effects are often termed social benefits and costs to distinguish them from the purely private costs and returns of the project. Social cost-benefit analysis is used to appraise the efficiency of private projects from a public interest viewpoint as well as to appraise public projects.

Public projects are often thought of in terms of the provision of physical capital in the form of infrastructure such as bridges, highways and dams, so-called “bricks and mortar” projects. However, there are other less obvious types of physical projects which augment environmental capital stocks and involve activities such as land reclamation, pollution control, fish stock enhancement and provision of parks, to name but a few. Other types of projects are those that involve investment in forms of human capital, such as health, education, and skill development, and social capital through drug use prevention and crime prevention, and the reduction of unemployment. While outside the notion of the traditional kind of project, changes in public policy, such as the tax/subsidy or regulatory regime, can also be assessed by cost-benefit analysis. There are few, if any, activities of government that are not amenable to appraisal and evaluation by means of this technique of analysis.1

Investment involves diverting scarce resources – land, labour, capital and materials – from the production of goods for current consumption to the production of capital goods which will contribute to increasing the flow of consumption goods available in the future. An investment project is a particular allocation of scarce resources in the present which will result in a flow of output in the future: for example, land, labour, capital and materials could be allocated to the construction of a dam which will result in increased hydro-electricity output in the future (in reality, there are likely to be additional outputs such as irrigation water, recreational opportunities and flood control but we will assume these away for the purposes of this example). The cost of the project is measured as an opportunity cost – the value of the goods and services which would have been produced by the land, labour, capital and materials inputs had they not been used to construct the dam. The benefit of the project is measured as the value of the extra electricity produced by the dam. As another example, consider a job training program: scarce resources in the form of classroom space, materials and student and instructor time are diverted from other uses to enhance job skills, thereby contributing to increased output of goods and services in the future. Or, third, consider a proposal to reduce the highway speed limit: this measure involves a cost, in the form of increased travel time, but benefits in the form of reduced fuel consumption and lower accident rates. Chapters 2 and 3 discuss the concept of investment projects and project appraisal in more detail.

The role of the cost-benefit analyst is to provide information to the decision-maker – the official who will appraise or evaluate the project. We use the word “appraise” in a prospective sense, referring to the process of actually deciding whether resources are to be allocated to the project or not. We use the word “evaluate” in a retrospective sense, referring to the process of reviewing the performance of a project or program. Since social cost-benefit analysis is mainly concerned with projects undertaken by the public sector, or with private sector projects which significantly affect the general community and consequently require government approval, the decision-maker will usually be a senior public servant acting under the general direction of a politician. It is important to understand that cost-benefit analysis is intended to inform the decision-making process, not supplant it. The role of the analyst is to supply the decision-maker with relevant information about the level and distribution of benefits and costs, and potentially to contribute to informed public opinion and debate. Ideally, the decision-maker will take the results of the analysis, together with other information, into account in coming to a decision about the project. Parties involved in the project may use the results of the analysis to inform their decision as to whether or not to participate under the terms laid down by the decision-maker. The role of the analyst is to provide an objective appraisal, and not to adopt an advocacy position either for or against the project.

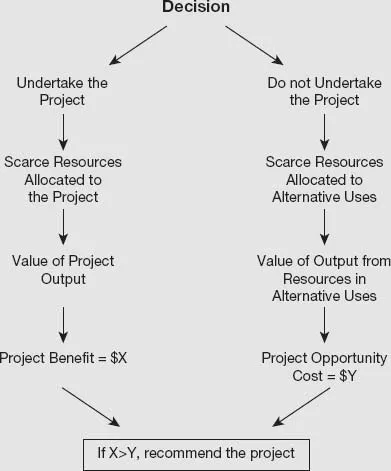

An investment project makes a difference and the role of cost-benefit analysis is to measure that difference. Two as yet hypothetical states of the world are to be compared – the world with the project and the world without the project. The decision-maker can be thought of as standing at a node in a decision tree as illustrated in Figure 1.1. There are two alternatives: undertake the project or don’t undertake the project (in reality, there are many options, including a number of variants of the project in question, but for the purposes of the example we will assume that there are only two).

The world without the project is not the same as the world before the project; for example, in the absence of a road-building project, traffic flows may continue to grow and delays to lengthen, so that the total cost of travel time in the future without the project exceeds the cost before the project. The time saving attributable to the project is the difference between travel time with and without the road-building project, which, in this example, is greater than the difference between travel time before and after the project.

Which is the better path in Figure 1.1 to choose? The with-and-without approach is at the heart of the cost-benefit process and also underlies the important concept of opportunity cost. Without the project – for example, the dam referred to above – the scarce land, labour, capital and materials would have had alternative uses. For example, they could have been combined to increase the output of food for current consumption. The value of that food, assuming that food production is the best (highest valued) alternative use of the scarce resources, is the opportunity cost of the dam. This concept of opportunity cost is what we mean by “cost” in cost-benefit analysis. With the dam project we give up the opportunity to produce additional food in the present, but when the dam is complete, it will result in an increase in the amount of electricity which can be produced in the future. The benefit of the project is the value of this increase in the future supply of electricity over and above what it would have been in the absence of the project. The role of the cost-benefit analyst is to inform the decision-maker: if the with path is chosen, additional electricity valued by consumers at $X will be available; if the without path is chosen, extra food valued at $Y will be available. If X > Y, the benefits exceed the costs, or, equivalently, the benefit/cost ratio exceeds unity. This creates a presumption in favour of the project, although the decision-maker might also wish to take distributional effects into account – who would receive the benefits and who would bear the costs – and other considerations as well.

Figure 1.1 The “with and without” approach to cost-benefit analysis. The decision tree has two paths: following the left-hand path by allocating scarce resources to the project will result in output valued at $X being produced. The right-hand path considers alternative uses for these scarce resources which would result in production of output valued at $Y.

The example of Figure 1.1 has been presented as if the cost-benefit analysis directly compares the value of extra electricity with the value of the forgone food. In fact, the comparison is made indirectly. Suppose that the cost of the land, labour, capital and materials to be used to build the dam is $Y. We assume that these factors of production could have produced output (not necessarily food) valued at $Y in some alternative and unspecified uses. We will consider the basis of this assumption in detail in Chapter 5, but for the moment it is sufficient to say that in competitive and undistorted markets the value of additional inputs will be bid up to the level of the value of the additional output they can produce. The net benefit of the dam is given by $(X − Y) and this represents the extent to which building a dam constitutes a better (X − Y > 0) or worse (X − Y < 0) use of the land, labour, capital and materials than the alternative use.

When we say that $(X − Y) > 0 indicates that the proposed project is a better use of the inputs than the best alternative use, we are applying a measure of economic welfare change known as the Kaldor-Hicks Criterion. The K-H criterion says that, even if some members of society are made worse off as a result of undertaking a project, the project is considered to confer a net benefit if the gainers from the project could, in principle, compensate the losers. In other words, a project does not have to constitute what is termed a Pareto Improvement (a situation in which at least some people are better off and no-one is worse off as a result of undertaking the project) to add to economic welfare, but merely a Potential Pareto Improvement. The logic behind this view is that if government believed that the distributional consequences of undertaking the project were undesirable, the costs and benefits could be redistributed by means of transfer payments of some kind. The problem with this view is that transfers are normally accomplished by means of taxes or charges which distort economic behaviour and impose costs on the economy. The decisionmaker may conclude that these costs are too high to warrant an attempt to redistribute benefits and costs. We return to the appraisal of the distributional effects of projects in Chapter 11.

Since building a dam involves costs in the present and benefits in the future, the net benefit stream will be negative for a period of time and then positive, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. To produce a summary measure of the net benefits of the project, all values have to be converted to values at a common point in time, usually the present. The net present value (NPV) is the measure of the extent to which the dam is a better (NPV > 0) or worse (NPV < 0) use of scarce resources than the next-best alternative. Converting net benefit streams, measured as net cash flows, to present values is the subject of Chapters 2 and 3.

When we compute present values for use in a cost-benefit analysis we need to make a decision about the appropriate rate of discount. The discount rate tells us the rate at which we are willing to give up consumption in the present in exchange for additional consumption in the future. It is often argued that a relatively riskless market rate of interest, such as the government bond rate, provides a measure of the marginal rate of time preference of those individuals participating in the market. However, it can be argued that future generations, who will potentially be affected by the project, are not represented in today’s markets. In other words, when using a market rate of interest as the discount rate, the current generation is making decisions about the distribution of consumption flows over time without adequately consulting the interests of future generations. This raises the question of whether a (lower) social discount rate, as opposed to a market rate, should be used to calculate the net present values used in public decision-making. This issue is considered further below and in Chapters 5 and 11.

Much of what has been said up to this point about public projects also applies to projects being considered by a private firm: funds that are allocated for one purpose cannot also be used for another purpose, and hence have an opportunity cost. Firms routinely undertake investment analyses using the same techniques as those applied in social cost-benefit analysis. Indeed, the evaluation of a proposed project from a private viewpoint is often an integral part of a social cost-benefit analysis, and for this reason the whole of Chapter 4 is devoted to this topic. A “private” investment appraisal takes account only of the benefits and costs of the project to the project’s proponent – its effect on revenues and costs and hence on pro...