![]()

Part I

What is crime?

![]()

Chapter 1

Defining and examining crime from different perspectives

How we define crime and criminality is of interest to both professionals and the layperson. Many disciplines, such as law, criminology, sociology and psychology, have provided definitions of what we mean by crime and criminality. In this chapter we will explore these different approaches and their understanding of crime and criminality. The introduction points us to how we are readily influenced by the media in our construction of what constitutes a crime and criminal behaviour, but it is the legal approach for a definition and understanding of crime and criminal behaviour that we will address first. Two important aspects of crime definition using a legal stance is the distinction between Latin terms actus reus (wrongful act comprising the physical component of a crime) and mens rea (a guilty state of mind necessary for proving guilt). In this chapter we will explore the use of actus reus and mens rea in the determination of an individual’s guilt. Circumstances where criminal responsibility can be mitigated against, such as age of criminal responsibility, impact of mental impairment and learning disability, ignorance or mistake of fact or law and acting in self-defence, will be explained. We will also explore within the legal approach, separate issues contextualising how law and punishment evolved. British laws can be traced back to King Henry VII in the late 1400s where a distinction between mala in se (morally wrong behaviour) and mala prohibita (legislative laws) was made. It is mala in se crimes, such as murder, where the role of religion had taken a strong lead in the determination of an individual’s punishment, and still continues to have a presence today in the form of Canon Law and Islamic Sharia. Religion plays an important role in formulating a consensus understanding of how we should behave and live our lives – in effect influencing our understanding of morality. This has had both a direct and indirect influence on English law and the laws of other countries. Using a cross-cultural perspective of laws and religious influence, we will explore the similarities and differences in jurisprudence (the study and theory of law) towards various types of crime. In particular, we will focus on serious crimes against the human moral code such as murder, rape, assault and genocide.

Since sociological and criminological perspectives of crime and criminality have made an impact on our understanding of how particular behaviours are perceived as criminal, in this chapter we will consider the four main approaches – consensus; conflict and critical criminology; social interactionism, including labelling; and discourse analysis. These perspectives originate out of a social constructionist ideology which are used as a methodological foundation for understanding crime and criminality. Although these approaches are considered primarily as arising from a sociological (and criminological) perspective, there is an extensive overlap with psychology (i.e. labelling and discourse analysis).

Psychology is our final discipline considered in this chapter. The three main areas of psychology addressing crime and criminality are psycho-legal, criminological and forensic psychology. Despite their common interest in criminal behaviour there are subtle differences in the areas of focus which will be addressed in this chapter. The definitions and understanding of crime and criminal behaviour used in psychology is generic across these three areas. Different aspects of the definition, however, might be considered differently depending on whether a psycho-legal, criminological or forensic psychological approach is taken.

Introduction

Psychologists, sociologists and criminologists have provided subtly different definitions of crime and criminal behaviour, but arguably none of these quite captures the ‘essence’ of what constitutes a crime and criminal behaviour. The difficulty of defining crime becomes obvious when asked the question of what is meant by the term crime. Children, for example, develop social constructions of robbers but, according to Dorling, Gordon, Hillyard, Pantazis et al. (2008), crimes and criminals are mere fictions that are constructed in order to exist. They argued that ‘crime has no ontological reality; it is a “myth” of everyday life’ (p.7). Dorling et al. (2008) are using the term ontological in this context to mean that crime does not exist in a literal sense but rather as a figurative concept. This might be one reason why it is difficult to describe the defining elements of criminal conduct but easier to provide examples of different types of crime. When asked to provide examples of different crimes, there appears to be a consensus of the types of crime that are remembered and these tend to be serious and punishable crimes like murder or burglary for instance.

What makes serious and punishable crimes most memorable has been attributed to how information about serious crime is disseminated by the mass media (Chermak 1995). Chermak showed that the media focus on reporting serious crime, such as murder, which then becomes over-represented at the expense of property related crimes – the public then perceive serious crime as more prevalent in society than other crimes. As this public perception is not supported by the data presented in the crime statistics and the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW, formally known as the British Crime Survey (BCS) prior to 2012), a consensus conception of what constitutes crime is created by the media. The BCS figures of 2009/10 formulated using interview data from respondents in 45,000 households, were analysed for serious (i.e. crimes against the person and robbery) and less serious (i.e. theft, burglary and vandalism) crime prevalence rates. Flatley, Kershaw, Smith, Chaplin and Moon (2010) found a 22 per cent prevalence rate for serious crimes versus a 66 per cent prevalence rate for crimes considered to be less serious. What these figures tell us is the nature of crimes that people are more likely to experience rather than the serious crimes communicated by the media. Hence Chermak’s findings suggest that we recall serious crimes when asked for a definition of crime because of a consensus understanding of crime provided by media coverage.

Identifying the factors that constitute a criminal act is not something we regularly think about – which might explain why we find it difficult to define what crime actually is. An example in Box 1.1 highlights the questions we should be asking when deciding whether a crime had taken place or not. Although this is a fictitious example it demonstrates the importance of an individual’s perception of the situation and the factors considered in the determination of whether the incident is reported as a crime or not.

An incident that could be a crime but at which point is it perceived as a crime?

If a man took £50 out of a friend’s wallet, kept in a drawer and failed to inform the owner and pay the sum back, has a crime been committed?

If the friend did not intend to deprive the owner of the money, then does this behaviour constitute a crime?

Assuming that the owner fails to notice the money missing then does this imply that no crime had occurred?

Assuming that the owner notices the money is missing (and realises his friend had taken it) but fails to inform the police then is this a ‘no crime’ situation?

If the owner informs the police but the police are not convinced that the money was stolen, then does this imply a no crime situation?

If the police decide not to prosecute against the friend, because he is on medication that has effects on behaviour, then does this imply that no crime has taken place?

If the friend’s case was discharged on the grounds of police pressure to confess to taking the £50 then does this mean that no crime had taken place?

If the friend is prosecuted and convicted of stealing £50, now has a crime been committed?

The stages and scenarios in Box 1.1 illustrate how the process of defining crime is multifaceted: the individual who commits a crime (i.e. the actor), the crime committed (i.e. the act) and the context (i.e. the physical and social environment, circumstances and provocation) all influence whether or not a crime is considered to have taken place. According to Quinney (1970) this suggests that a ‘crime’ is a socially defined phenomenon that cannot be isolated from the social context in which it occurred. Even the terms used to describe individuals who commit crime (i.e. criminal, offender, perpetrator, felon, culprit or delinquent) are derived from a social process known as labelling (to describe or classify someone in a word or short phrase). Labelling influences how behaviour is perceived by the observer and whether it is considered to be a criminal act. Once the behaviour is labelled as a criminal act, it is then the observer’s decision to inform the police.

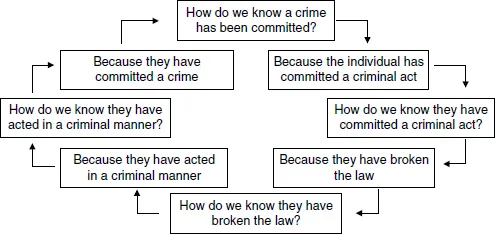

Reporting to the police that a crime has occurred is the first stage towards acknowledging a criminal event and implying that we know when a crime has been committed. Knowing when a criminal act has occurred, however, can be a tautological problem as demonstrated in Figure 1.1.

Hence defining crime is difficult, but Andrews and Bonta (1998) have nevertheless introduced a succinct working definition as ‘[a]ntisocial acts that place the actor at risk of becoming the focus of the attention of the criminal and juvenile professionals’. Of course some might consider this definition to be tautological. Andrews and Bonta (1998) elaborated further by offering four definitions of crime and criminal behaviour using legal, moral, social and psychological perspectives. In the case of a legal perspective, criminal behaviour is prohibited by the law of the land and is punishable using the legal processes of that law. Adler, Mueller and Laufer (2004) defined crime as ‘the violation of some law that causes harm to others’. Crowther (2007) defined crime as consisting of acts that contravene the law and are therefore punishable by the criminal justice system. Crowther (2007), however, also recognised that a legal definition can be limited given that laws are not consistently standardised across different countries. This makes direct comparisons of what constitutes criminal behaviour across different countries less reliable. In the case of a moral perspective, criminal behaviour that violates norms stipulated in religious and moral doctrine is considered to be punishable by a supreme spiritual being such as God. A social perspective views criminal behaviours as a violation of socially defined behaviours. These socially defined behaviours are based on our customs and traditions, which is why it is considered fitting that individuals who contravene these should be punished by the community. A psychological approach considers the actions of an individual as criminal if the rewards received from their criminal actions are at the expense of causing harm or loss to others (Andrews and Bonta 1998).

Figure 1.1 Tautological argument of knowing when a criminal act was committed

Because these four definitions consider different perspectives, Andrews and Bonta in 2006 conceded that there is no single satisfactory definition that captures the essence of a crime. It is difficult to endorse one type of definition to suit all, given that each country has its own cultural context that impact on morals, values and beliefs about crime and criminal behaviour. A socially constructed understanding of crime might be more appropriate than a legal definition, but it is nevertheless important to understand the legal stance on criminality given that the law is there to apprehend and punish offenders. There are three approaches to understanding crime and criminal behaviour that will be considered in the next section: the legal approach, the sociological and criminological approach (i.e. social constructionism) and the psychological approach (psycho-legal; criminological (or criminal) and forensic psychology).

Definitions of crime and criminal behaviour

The legal approach

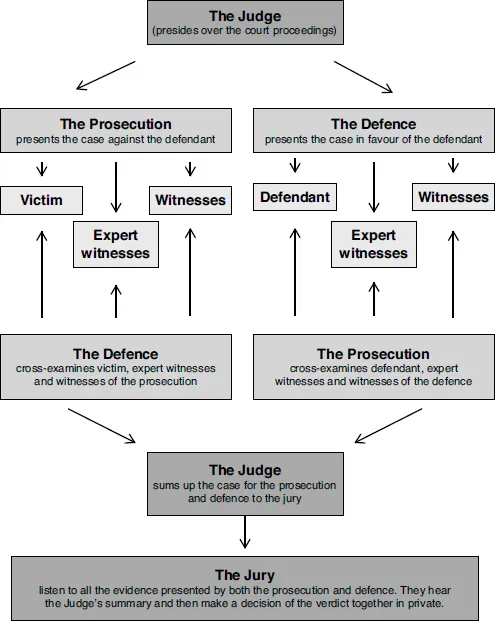

Legal processes prescribed in Acts of Law (legislations that have been passed by Parliament and considered as part of law) are used by the criminal justice system to apprehend, prosecute and sentence individuals who have contravened the law. In the UK police are involved in the investigation of crimes with the objective of solving the case by apprehending and arresting the perpetrator. Once there is enough evidence on which to arrest the individual suspected of committing the crime (i.e. the suspect), a court case is prepared, and the suspect now known as the defendant, attends the courtroom and awaits his or her verdict. If found guilty then the judge decides the type of punishment – hence the defendant is sentenced. If the defendant is sentenced to imprisonment then he or she becomes a prisoner. In the UK the courtroom procedure is highly stylised as shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Outline of a typical courtroom procedure

Taylor 2015. Reproduced with kind permission from Taylor and Francis.

Legal processes, however, differ cross-culturally (Andrews and Bonta 2006) and do so as a consequence of variations in cultural infrastructure (Crowther 2007). Despite these variations, McGuire (2004) has argued that there is international congruency in the definition of serious crime and in the treatment by the criminal justice system of individuals who commit serious crimes such as murder and sex offences. Cross-cultural differences of legal implementation and practice, however, are a recognised problem that the International Criminal Court (ICC) has tried to overcome. The ICC Statute was adopted in Rome in 1998 as a declaration with intent to subject different state sovereignty to an international criminal jurisdiction.

According to Cassese (1999), the ICC Statute or Roman Statute, as it is also known, can be considered in two ways: first, as an international treaty law, and second, in terms of its contribution towards substantive (statutory or written law) and procedural (rules governing how all aspects of a court case are conducted) international criminal law. As an international treaty, the Roman Statute discusses the political and diplomatic variations across different countries and is upfront in highlighting the problems it faces at solving anomalies in the major issues of law. It is in substantive international law that the Roman Statute has made advances (Cassese 1999). One of the main differences between national law and international law relates to the principle of specificity. This principle requires that criminal rules have clarity and transparency which means that core elements of a crime must be detailed and defined. This can be seen in the case of a murder charge, where details of what constitutes murder in the first degree are separate from manslaughter. Likewise the type of sentence and length of sentence are clarified and made transparent to...