![]()

1

If one is interested in how an old building came to assume its present form, it is useful to examine its foundations and original layout. So, too, with regions like East Asia. Geography, race, language, ethnicity, subsistence patterns, social structures, political institutions, and belief systems constitute their “ground plan.” Unlike buildings, of course, regions are not the product of conscious design, and they lack a clearly defined starting point. There is no single or original ground plan for East Asia. Its architecture was quite different in, say, 500 B.C.E., and 500 C.E., and 1500 C.E., to select random dates on an evolutionary continuum stretching back into prehistory. One can partially get around this difficulty by emphasizing features that remain relatively constant and that are particularly relevant to understanding the modern scene. The result will be a composite sketch weighted toward more recent times. It should be borne in mind, however, that the reality was constant and kaleidoscopic change. The once widespread notion of an “unchanging Asia” is a Western myth that tells more about Westerners and their preoccupations than the societies it purports to describe.

Geographical Setting

Geographically, the most striking feature of East Asia is its relative isolation from the rest of the Eurasian land mass. The Himalayas and Indian Ocean divide it from South Asia, and the steppes and deserts of Central Asia separate it from West Asia. These barriers were never, of course, impenetrable. From early times, the famous Silk Road caravan route across Central Asia linked China with West Asia, and maritime trade across the Indian Ocean connected South and Southeast Asia. Cultural exchange accompanied trade. East Asia appropriated Buddhism and Islam from South and West Asia, along with cotton, refined sugar, and Indian numerals and mathematics. In turn, East Asia transmitted Chinese inventions such as gunpowder, paper, printing, the compass, and porcelain. Nevertheless, East Asia’s contacts with other regions were limited before the era of modern transportation and communications. For example, the empires that grew up in China and India had virtually no political or military interaction with one another. In premodern times, West Asia, South Asia, and Europe were more closely linked with each other in a wider range of fields than any of them was with East Asia.

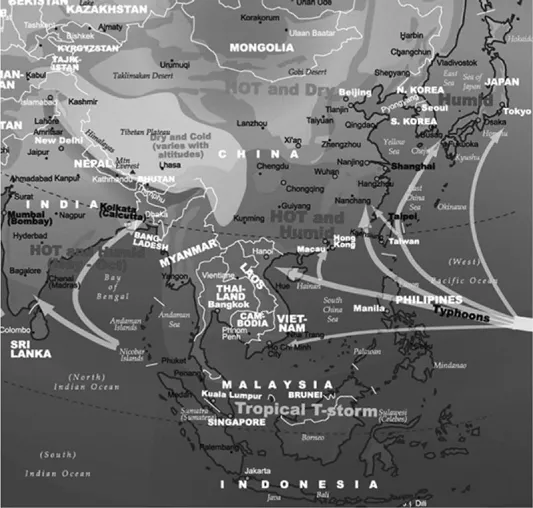

Within East Asia, geography unites as well as divides. One unifying phenomenon is the monsoon, which East Asia shares with South Asia. In summer, moist oceanic air flows inward toward Central Asia, dropping heavy rainfall on Southeast Asia, eastern China, Korea, and Japan. In winter, cool dry winds blow outward from Central Asia. These bring copious amounts of wind-borne dust from the Gobi Desert, which blankets northern China and contributes to the unusual fertility of the soil there. In the age of sail, monsoonal winds largely determined maritime navigation, since ships could move only with the prevailing ones—northeasterly in summer and southwesterly in winter. Monsoonal rainfall patterns also influence agriculture. The coincidence of heavy rains with warm weather permits intensive agriculture and double or even triple cropping. In many parts of island Southeast Asia, however, monsoonal rains leach the naturally poor soils of nutrients. Combined with the heavy forest cover there, this limited agriculture in premodern times, resulting in relatively small and scattered populations.

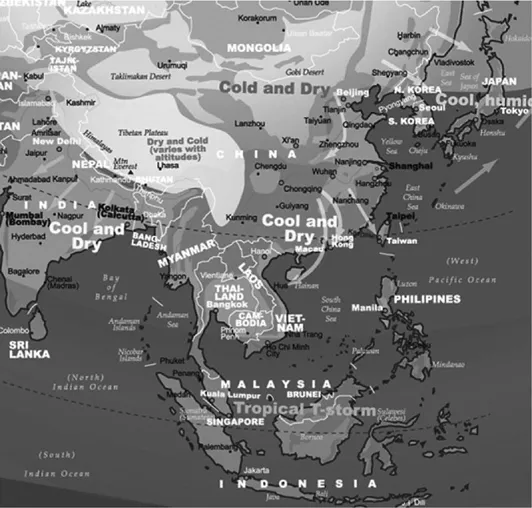

Climatically, East Asia is highly diverse, with a range of ecosystems similar to the eastern seaboard of North America. In the north, coniferous forests extend from the tundra line in northeastern Siberia to the fringes of Manchuria and Mongolia, encompassing the area Russians call their “Far East.” Here winters are harsh and summers short, discouraging agriculture. Inner Asia—the arid steppes, deserts, and plateaus that curve around China from Manchuria through Mongolia and Xinjiang (Chinese Turkestan) to Tibet—is also inhospitable to agriculture and sparsely inhabited. Climatically and to some extent culturally, this area is an eastern extension of Central Asia. Northern and central China, Korea, and Japan comprise East Asia’s temperate zone, characterized by mild winters and hot summers. Warm oceanic currents contribute to the mildness of the climate. China south of the Yangzi (Yangtze) River is subtropical, while most of mainland and island Southeast Asia falls within the tropics and has year-round high temperatures with little seasonal variation.

Continental East Asia is dominated by great river systems that rise in the Tibetan massif and flow eastward and southward, forming the region’s main centers of agriculture and population. The Yellow (Huang) River turns the fertile soil of northern China into an agricultural breadbasket, although its frequent floods earned it the sobriquet “China’s Sorrow.” The Yangzi system performs the same function for central China. Because of its milder climate, which permits more intensive agriculture and a greater variety of crops, the Yangzi basin is China’s economic and demographic center of gravity. The smaller West River serves China’s far south. Together, the Yellow, Yangzi, and West river watersheds comprise the Chinese heartland. Four river systems drain mainland Southeast Asia and set apart its major peoples. The Red (Hong) River valley is the homeland of the Vietnamese. The middle and lower Mekong valley are home to the Laotians and Cambodians (Khmer), respectively. Thailand centers on the Chaophraya valley, while Burma is based on the Irrawaddy basin. The intervening uplands are occupied by many ethnic minorities such as Shans, Karens, and Hmong.

Eastern Asian summer weather patterns.

As noted above, the tropical rain forests and poor soils of the Malay Peninsula and Indonesian and Philippine archipelagos kept their populations small and dispersed until recent times. The area’s many island habitats also contributed to this. Farmers clustered in coastal enclaves, often leaving the heavily forested interior to mobile bands of hunter-gatherers like the Dyaks of Borneo (Kalimantan). Only a few of the larger islands, notably Java, supported agricultural populations comparable to those of Burma, Thailand, and Vietnam. But the islanders were skilled seafarers and traders, and the surrounding seas linked them with mainland Southeast Asia and southern China. In contrast, the Korean Peninsula and Japanese archipelago are well suited to agriculture, and developed large farming populations. Both are also relatively isolated. This is less true of Korea, which is accessible by land from Manchuria. Like Britain, however, Japan is a continental outlier. It was historically a cultural and genetic cul-de-sac, mixing influences from eastern Siberia through Hokkaido, from China and Manchuria mediated by Korea, and from Southeast Asia transmitted through the Ryukyu Islands.

Eastern Asian winter weather patterns.

Race, Language, and Ethnicity

Most East Asians are members of the so-called “Mongoloid race,” one of the principal racial categories that were until recent years widely employed to classify humankind. The others are the “Caucasoid,” “Negroid,” and “Australoid” races. Nowadays this racial scheme is looked upon askance in many quarters, in part because of the superficiality and variability of the physical traits on which it is based. Those of “Mongoloids” include straight black hair, sparse body hair, and narrow, fleshy eyelids featuring what is known as the “epicanthic fold.” It is hypothesized that people with these characteristics evolved in northern Asia during the last ice age, and subsequently spread into Southeast Asia and across the Bering Strait into the Americas. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that some of their physical traits, such as the epicanthic fold, appear to be cold climate adaptations. It is also consistent with the archaeological record, which points to population movements in post-glacial times from Northeast to Southeast Asia, and the assimilation of pre-Mongoloid, mainly “Australoid” peoples. The Ainu of northern Japan and the Semang of the Malay Peninsula are among the modern survivors of these peoples.

Race offers a crude means of differentiating East Asians from their neighbors. The inhabitants of South and Central Asia are chiefly Caucasoid, while those of Australia and New Guinea are—or in the case of Australia, were—Australoid with some Negroid elements. But the Mongoloid peoples of East Asia are physically diverse, and the divisions between them and other racial groups blur at the edges. Northern Chinese are, for example, generally taller and have sharper facial features than southern Chinese, who more closely resemble Southeast Asian “southern Mongoloids.” Some East Asian populations are racially mixed. For example, the peoples at the eastern end of the Indonesian Archipelago exhibit Australoid traits, while those in the Himalayan borderlands and northwestern China display Caucasoid features. Likewise, as one legacy of Spanish colonial rule, the Filipino elite carries a substantial admixture of European genes. Modern population movements further complicate the picture. Until the nineteenth century, the Russian Far East was sparsely inhabited by Mongoloid groups such as the Tungus. Today, however, the area is populated mainly by European Russians.

Language provides another lens through which to examine the peoples of East Asia. Linguists have identified a number of world language families based on structural similarities among seemingly unrelated languages. Given their racial affinities and geographical proximity to one another, one might expect languages spoken by East Asians to belong to the same language family. But this is not the case. There are no less than five families represented in the region: Altaic (including Turkish, Mongolian, Korean, and Japanese); Sino-Tibetan (Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese); Tai (Thai, Lao, Shan); Austroasiatic (Vietnamese, Cambodian, Mon); and Austronesian (Malay with Polynesian and Malagasay outliers). It is not clear what accounts for this linguistic diversity. A now lost ancestral “super language” may have given rise to some of these families. The common origin of Tai, Austroasiatic, and Austronesian speakers in southern China points in this direction. But it is also possible that the families in question are unrelated and evolved over many millennia in different ecological and cultural settings. This seems to be the case with the neighboring but profoundly dissimilar Altaic and Sino-Tibetan language groups.

The heterogeneity of East Asians is even more striking if the focus shifts to ethnicity or group identities built around real or imagined ties of blood, history, language, religion, and customs. Although there is a large number of such self-defined ethnic groups in the region, the most numerous by far are the “Han Chinese,” so named after the Han Empire that politically unified the Chinese heartland some twenty-two hundred years ago. Like most ethnic groups, contemporary Han Chinese assume that they have always existed as a distinct people. In fact, however, the formation of Chinese ethnic identity was a lengthy process that involved the southward expansion of the North Chinese and their assimilation of culturally and physically dissimilar groups in central and southern China. Vestiges of this process include the survival of southern “dialects” like Cantonese and Fukienese, which are closely related to the “Mandarin” tongue of the North Chinese but are separate languages. Similar processes of assimilation and acculturation characterize the evolution of other ethnic groups such as Japanese, Thai, and Javanese.

Although ethnic identities are “constructed” and changeable, they can also be extremely durable. Vietnamese, Mongolians, and Tibetans were at various times incorporated into China, but they never lost their sense of uniqueness or came to see themselves as Chinese. The main exception is the Manchus, who ruled China between the mid-seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, and were absorbed into the Chinese fold through intermarriage and Sinicization. In general, ethnic identities are strongest where geographical barriers, distinctive habitats, cultural differences, or long-standing conflicts keep groups apart. Insularity played a major role in the formation of the Japanese and the many ethnic groups occupying islands in the Philippine and Indonesian archipelagos. River basins unified groups like the Thai, Vietnamese, and Burmese. Differences between uplanders and lowlanders, pastoralists and agriculturalists, and coast and interior dwellers also generated ethnic cleavages. Religion, too, is often a key marker of ethnicity, since it taps deeply held beliefs. Examples include the Islamic faith of the “Moros” of the southern Philippines and the Shinto folk religion of the Japanese.

Like other forms of group identity, ethnicity involves a consciousness of separateness from, and superiority to, outsiders. In premodern East Asia, this “we feeling” was defined in civilizational terms and gave rise to shared traditions and myths. Chinese saw themselves as forming an oasis of civilization in a desert of barbarism, and as the heirs of a timeless and near perfect sociopolitical order. Japanese imagined themselves to be divinely descended and, as such, possessed of peerless virtues and institutions. Koreans prided themselves on their mastery of China’s Confucian civilization, which made them equal to the Chinese and superior to the Japanese. Vietnamese also supposed that they had carried Chinese civilization to a pinnacle of perfection and looked down upon their “barbaric” Buddhist neighbors. Cambodians recalled the lost glories of the Khmer Empire, making the depredations of the Vietnamese and Thai all the more humiliating. Mongols, too, looked back to a golden age under their Great Khans when they had ruled China and much of Eurasia. Both Thai and Burmese regarded themselves as martial peoples destined to rule their weaker and less civilized neighbors.

Social and Economic Patterns

The principal socioeconomic divisions in East Asia before modern times were among the nomadic pastoralists of Inner Asia’s steppes and deserts, the rice farmers of Southeast and Northeast Asia, and the hunter-fishers of the northern forests. This tripartite division reflects the climatic factors discussed above. The low temperatures and heavy forest cover of the Russian Far East make it unsuitable for farming and herding or, indeed, any mode of subsistence except foraging. The small bands of Altaic-speaking hunters who roamed this area kept largely to themselves. In contrast, Inner Asian pastoralists interacted closely with China and often menaced it. The grasslands of Manchuria and Mongolia, deserts of Xinjiang, and high plateaus of Tibet are too arid for farming. But they are ideal for herding horses, sheep, camels, and yaks. Mongols and other pastoralists who specialized in this way of life moved seasonally in search of pasture and had few permanent settlements. Although not numerous, they were skilled horsemen and archers. Before the sixteenth-century Gunpowder Revolution, their mobile war bands could often outmaneuver and destroy slower-moving Chinese peasant armies.

The agrarian societies of Northeast and Southeast Asia were based on farming of the most intensive sort, which was quite unlike anything practiced by Europeans. The general pattern was irrigated or wet-rice agriculture. Rice is one of the most nutritious cereals, but its cultivation is incredibly demanding and labor intensive. It entails the preparation and maintenance of flat, irrigated fields; the laborious hand-transplanting of seedlings; and their careful weeding and fertilizing. All of this requires many hands and close teamwork. The payoff is much higher yields per acre than dry field crops such as wheat, the European staple. Thanks to the favorable climatic conditions noted earlier, moreover, double cropping is carried out in many areas. Rice cultivation is not confined to East Asians, but their specialization in it is unusual. Its main effect was the creation of dense concentrations of farmers on a scale that boggled the European mind. In 1800, for example, China alone contained about 300 million people, or more than ten times the population of France, then Western Europe’s most populous country.

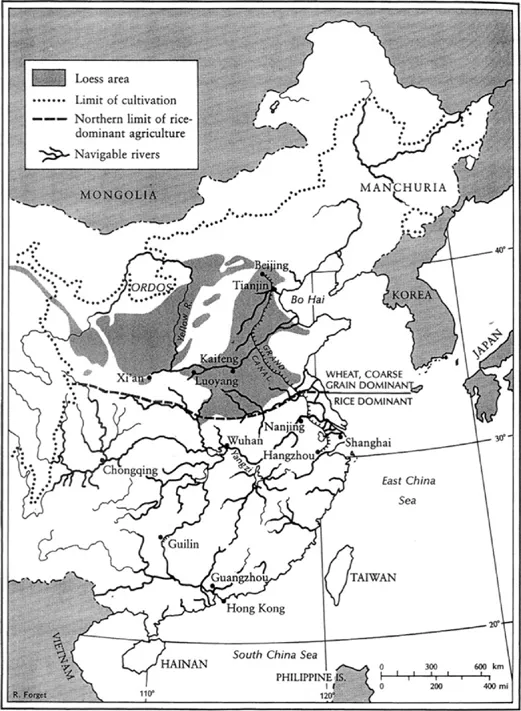

China’s agrarian economy was unique in East Asia not only by virtue of its enormous size, but because it was not exclusively based on irrigated rice. The North China Plain around the Yellow River, which is the original homeland of the Chinese, is too cold and dry for rice. It is, however, well suited to wheat and millet, which became the staple crops of the early Chinese. Their labor-intensive farming methods, combined with the area’s fertile soil and irrigation systems based on the Yellow River, made for both high productivity and a large population. The flowering of Chinese civilization in northern China in the second and third millennia B.C.E. was no accident. Its agricultural surpluses facilitated class differentiation, the rise of cities, the formation of kingdoms, and the development of metallurgy, art, and writing. As the eastern terminus of Central Asian trade routes, moreover, northern China was exposed to cultural influences emanating from other early centers of civilization in West and South Asia. While these influences are difficult to assess, they probably spurred indigenous trends such as the transformation of Chinese writing from simple pictographs to complex ideographs expressing abstract thought.

Northern China was similar to the rice-growing areas of East Asia insofar as its political and social superstructures rested on a mass of “peasants,” or self-sufficient farmers who cultivated small plots of land and spent their lives in village communities consisting of a few dozen to a hundred or more nuclear families. The world of peasants revolved around duties and loyalties to their family and village groups. The individual, as such, was not important and was, in fact, expendable. For most peasants, life was hard and precarious even in the best of times. Flood, drought, famine, and pestilence were ever-present dangers, and there were no safety nets except those provided by family and village. Peasant communities were neither socially undifferentiated nor necessarily harmonious. But survival in an unpredictable environment and the requirements of labor-intensive agriculture dictated the celebration of communitarian values and respect for authority. Periodic festivals and rituals reinforced communal solidarity. Another purpose of these ceremonies was to propitiate the supernatural beings and forces that peasants believed controlled their individual and collective fates.

Agricultural zones of China.

In many parts of agrarian East Asia, peasantrie...