Introduction

The Oxford English Dictionary defines crime as ‘an action or omission which constitutes an offence and is punishable by law’. However, whilst a contravention of legislation might sound simple to define and record, it is far from so in reality. What constitutes a crime will vary from country to country and over time. What was once defined as criminal is repealed or decriminalised due to social and cultural developments. For example, suicide was decriminalised in Northern Ireland in 19662 and in the Republic of Ireland in 1993.3 Similarly, new criminal offences are enacted. These may stem from new technologies, which facilitate new methods of offending, or from general trends and behaviours in society which the legislature seeks to reduce or curtail. Additionally, a crime only becomes a crime ‘when influential human beings have decided what meaning to attribute to it’ (Box, 1981: 162).

This chapter considers police-recorded crime statistics between 1963 and 2013 in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, both independently and in an international context. It considers briefly the impact of reporting rates and attitudes towards the police on the recorded crime figures over recent years. Following this, the results from domestic and international crime victimisation surveys in both jurisdictions are examined. A number of factors which may contribute to increases or decreases in crime, such as the proportion of young males in each jurisdiction, are discussed. The contrasts and similarities between police-recorded and victim-reported crime are outlined, and some possible explanations are offered for the divergent trends evident. Finally, areas in need of additional research are proposed.

Examining trends in crime – data sources and limitations

A myriad of issues must be considered when seeking to analyse crime statistics both within and across different jurisdictions. The most basic of these relates to the fact that there is no way to measure with complete accuracy the number of crimes which are committed in any country. Hypothetically, there is a true crime rate, which consists of all acts that contravene legislation and hence are legally defined as criminal. To be ‘counted’ however, a criminal act must not only constitute a contravention of law but must also be reported and recorded as such.

The decision to report a crime

A person or entity who has been the victim of a crime may not necessarily report their victimisation to the police for a variety of reasons. In terms of crimes against property, a victim may choose not to report because they believe the crime is too minor, or there has been no/limited financial loss. Typically, such crimes include vandalism/criminal damage and attempted burglaries (van Dijk et al., 2007a; CSO, 2010; PSNI, 2014). In terms of crimes against the person, a victim may choose not to report because they do not wish to subject themselves to the intrusion of a criminal investigation, feel ashamed, believe the crime was too trivial or because it happened a substantial period of time ago. Typically, such crimes include victims of sexual, domestic or child abuse (McGee et al., 2002;Watson and Parsons, 2005).

Unreported crime

Nevertheless, certain unreported crimes may come to the attention of the police during the course of their day-to-day duties or as a result of specific enforcement initiatives. Such enforcement initiatives can lead to substantial, if short-term, increases in recorded crimes. There is a correlation therefore between reporting rates, policing priorities and activity and the amount of crime recorded.

There will also be a number of crimes which have occurred that are not reported or disclosed at all, for example, crimes that do not have a direct victim or that have an offender who is already in conflict with the law. However, even if a crime is reported to the police, it must be recorded as such before it will appear in a jurisdiction’s crime statistics.

The decision to record a crime

Just because a crime has been reported or the police are aware a crime has taken place, it does not necessarily mean that the crime will be recorded. Two factors impact at this stage. The first is police discretion and the second relates to the nuances of police recording systems and procedures.

Discretion is a legitimate police power which is used to decide which course of action to take in a given situation. That decision may be to take no action. This may be motivated by a number of factors, including a desire to avoid criminalising people for offences which have come to police attention. Whilst the law can guide many police actions, it cannot provide absolute clarity for every situation a police officer will encounter; police must also use their own judgement. A police officer:

[C]annot decide to arrest, warn, caution … a suspect simply by taking into account the legal facts of the case. Consequently, he has to introduce other criteria: these usually reflect his personal values, beliefs and prejudices, and those of the social group with whom he identifies.

(Box, 1981: 171)

Police officer training, instructions from supervisors and policies of the police service will also influence the level of discretion employed. Whilst discretion is essential to enable the police to function efficiently, it is also a contentious issue. It can be difficult to ensure that discretion is employed in a fair and consistent manner and that the police are accountable for the discretionary decisions they make. Academic authors have noted that police attention and interaction, both with suspects and victims, can be disproportionately focused and ‘[T]ypically comprises individuals and groups who are marginalised in some way (people who are on low incomes, young in age, and of ethnic minority background are typically over-represented)’ (Healy et al., 2013: 16). This is often because these groups spend more time in public places and hence are more likely to come to police attention.

The second issue is that the total amount of crime reported to the police is not the same as the total amount of crime recorded (or counted) by the police. Many jurisdictions have formal recording procedures and crime counting rules. In the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, a crime must be recorded if, on the balance of probability, the police believe a crime occurred and there is no credible evidence to the contrary.4 Crime counting rules also apply in both jurisdictions; a significant example of this is the primary/principal offence rule. This dictates that when multiple criminal acts are committed within one episode, only the most serious offence5 is counted. Both jurisdictions give primacy to offences against the person over offences against property. So, for example, if a home is entered, the householder is raped and their car stolen, the rape will be counted. It is important to note that the police record reported crimes for operational use. Hence, whilst they provide some representation of police workload, they do not, nor are they intended to, represent the total level of crime which actually occurs. During periods where there are no substantial changes in crime counting and recording rules or in victim reporting rates, police crime statistics can also be useful to ascertain general trends in crime.

The police are not the only agencies responsible for law enforcement however; others include Revenue – Irish Tax and Customs, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, as well as An Post/ BBC/TV Licensing. Offences reported to/recorded by other law enforcement agencies may be published, for example, in lists of tax defaulters published by the respective revenue services. Where settlements are reached these acts may not be officially labelled as ‘criminal’.

Measuring crimes not reported to the police

Crime victimisation surveys are used to elicit details of crimes not reported to the police. They do not, however, include the full range of the criminal law, as some offences are deemed too sensitive for inclusion, such as sexual offences or offences against children. There are also surveys conducted by the private and/or commercial sector which attempt to measure crimes against businesses,6 as there may be some reluctance to report such crimes due to commercial sensitivities. Other crimes may be disclosed to certain other agencies or services but not to the police or crime victims’ surveys. An example of such disclosure would be experience of rape if victims attended for medical treatment or to make use of other support services. Some such agencies publish details of the use of their services which may be useful when considering victimisation trends.7

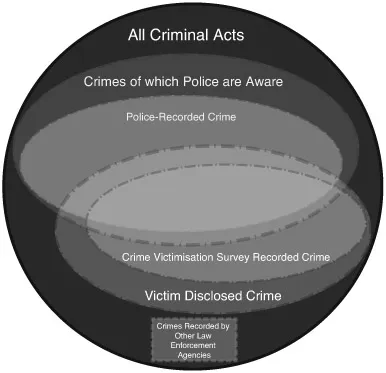

The configuration of crime statistics

The outer circle in Figure 1.1 represents the absolute total amount of crime in any jurisdiction. The various internal shapes show the configuration from different sources of reported and recorded crime. The area of the circle not covered by any internal shape represents all crime which is unrecorded via any source.

The first source of data considered when examining crime trends in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland are police-recorded crime statistics. As outlined, these must be considered in the context of the rules pertaining to recording; the most significant issues are outlined briefly below and sources of additional information are provided.

Figure 1.1 The configuration of crime statistics

Police-recorded crime statistics

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI),8 in common with all constabularies in England and Wales, adheres to the Home Office crime recording standards.9 These state that all notifiable offences (previously, indictable offences) are recorded and published in crime statistics.10 Notifiable offences are all those which could possibly be tried by a jury (i.e. in a Crown Court or higher) and also includes some less serious offences, such as minor thefts. The crime statistics do not include details of non-notifiable offences.11 Figures are published by the PSNI in annual reports and figures dating back to 1968 and are available online.12

The Garda Annual Reports from 1922 to 2005 include full details of the number of recorded indictable offences13 in the Republic of Ireland. Indictable offences have a similar meaning to Northern Ireland, in that they could be tried by a jury (i.e. in the Circuit Court or higher). Whilst not publishing figures on the total number of non-indictable offences recorded, the Garda Síochána did publish figures on the numbers of persons proceeded against for non-indictable offences. The Central Statistics Office (CSO) took responsibility for the publication of crime statistics in 2006 and introduced a new Irish Crime Classification System (ICCS). Under the ICCS, statistics on all crime recorded by the Garda Síochána (both what was previously indictable and non-indictable) were published for the first time. This led to a substantial increase in the overall total crime figures. The CSO has since published crime statistics according to the ICCS dating back to 2003. This chapter uses CSO-supplied indictable recorded crime figures for 2003 to 2013.

In both jurisdictions, over the time period examined, there have been changes to the crime counting rules used by the respective police services.14 Additionally, new computerised crime recording systems have been introduced (ICIS15 and NICHE in Northern Ireland, PULSE16 in the Republic of Ireland). Both of these factors create breaks in the data series. It would be expected also that the improvements in recording brought about by the new systems would lead to increases in recorded crime figures.

Trends in police-recorded crime statistics

Trends between 1963 and 2013

Crime trends over a fifty-year span (from 1963 to 2013, the most recent available) were examined to provide a long-term view within each jurisdiction. This time period also encompasses significant social and cultural changes. At the macro level, there have been differing trends in the population of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. With the exception of some dips in the late eighties and early nineties, the population of the Republic of Ireland has grown incrementally from under 3,000,000 to over 4,500,000. In Northern Ireland, the population remained around 1,500,000 until the early eighties (with some reductions in the seventies) and has since grown slowly to over 1,800,000. There has been significant political and civil conflict in Northern Ireland17 from the late sixties until the late nineties, which also impacted the Republic of Ireland.

Both jurisdictions have become more densely populated and urbanised. Household sizes have reduced dramatically, but the number of rooms per household has increased. From a time when most homes did not have a television, washing machine or landline telephone, there has been a substantial increase in the number of electronic appliances invented and present in the majority of homes – from video cassette recorders to DVD players; games consoles to music players and mobile phones. Car ownership has also greatly increased. In the Republic of Ireland particularly, the ‘Celtic Tiger’ roared, and then the economy fell into a deep and prolonged recession. There have been peaks in unemployment, in both jurisdictions during the eighties and again since 2009, which are now beginning to decline again.18 All of these changes in society and the increased availability of tempting targets have influenced crime trends to some extent.

In 1963 the Gardaí recorded 16,203 crimes in the Republic of Ireland, and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) recorded 10,859 crimes in Northern Ireland. By 2013, there were 113,019 crimes19, officially recorded in the Republic of Ireland and 102,746 in Northern Ireland. Crudely considering the total time period, recorded crime increased by almost seven times in the Republic of Ireland (698 per cent) and over nine times in Northern Ireland (946 per cent). Figures 1.2 and 1.3 present the annual figures for both jurisdictions. What ...