This is a test

- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In order for students to write effective informational texts, they need to read good informational texts! In this practical book, you'll find out how to use high-quality books and articles to make writing instruction more meaningful, authentic, and successful. The author demonstrates how you can help students analyze the qualities of effective informational texts and then help students think of those qualities as tools to improve their own writing. The book is filled with examples and templates you can bring back to the classroom immediately.

Special Features:

-

- Offers clear suggestions for meeting the Common Core informational writing standards

-

- Covers all aspects of informational writing, including introducing and developing a topic; grouping related information together; adding features that aid comprehension; linking ideas; and using precise language and domain-specific vocabulary

-

- Includes a variety of assessment strategies and rubrics

-

- Provides classroom snapshots to show the writing tools in action

-

- Comes with a variety of templates and tools that can be photocopied or downloaded and printed from our website, www.routledge.com/books/details/9781138832060

Bonus! The book includes an annotated bibliography—a comprehensive list of recommended informational texts, with suggestions for how to use them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Informational Writing Toolkit by Sean Ruday in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Informational Writing Strategies Aligned with the Common Core Standards for Grades 3–5

1

Introducing a Topic

What Does “Introducing a Topic” Mean?

A fundamental step of effective informational writing is introducing the topic of a piece in a clear and engaging way. The Common Core Writing Standards highlight the importance of this concept, as Standards W.3.2a, W.4.2a, and W.5.2a emphasize the value of introducing a topic when writing informational text. In this chapter, we’ll discuss the following: what “introducing a topic” means, why this concept is important for effective informational writing, a description of a lesson on this concept, and key recommendations for helping your students effectively introduce topics in their own informational writing.

Let’s begin by examining what it means to introduce a topic. An introduction to a piece of informational writing is an opening section of one or more paragraphs that provides a brief “first look” at subject matter that will be further developed later in the text. For example, the informational book Reptiles by Melissa Stewart (2001) contains an introductory paragraph that shows the reader what the rest of the book will address in more detail: “A snake flicks its long tongue as it slithers along the ground. A turtle sits on a rotting log and basks in the sun. A crocodile grabs a fish with its mighty jaws. These are the images that come to mind when someone says the word ‘reptile’” (p. 5).

Stewart’s introduction provides enough information to illustrate to the reader that this book is about reptiles, but doesn’t yet go into a great amount of detail. The “first look” provided by this introduction conveys the topic of this book, inviting readers to continue reading the text. In the next section of this chapter, we’ll consider why creating an effective introduction is important to well-written informational texts.

Why Introducing a Topic is Important to Effective Informational Writing

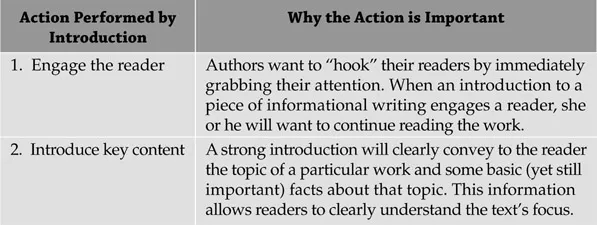

Introducing a topic is important to effective informational writing because a well-crafted introduction should perform two key actions: 1) Engage the reader; and 2) introduce key content. A strong introduction to a piece of informational writing does more than begin a piece—it opens the work in a clear and purposeful way that shows the author’s ability to capture the reader’s attention while also conveying basic information about the book’s topic. Figure 1.1 illustrates the two key actions introductions perform and why each one is important.

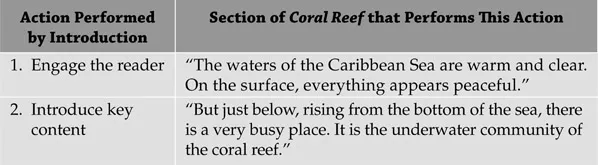

In this section, we’ll discuss why these concepts are related to an effective introduction using some published works to illustrate how professional writers apply these principles to their own introductions. Let’s begin by examining the opening section of Gary W. Davis’ (1997) informational text Coral Reef: “The waters of the Caribbean Sea are warm and clear. On the surface, everything appears peaceful. But just below, rising from the bottom of the sea, there is a very busy place. It is the underwater community of the coral reef” (p. 4). In this introductory passage, Davis both engages the reader and introduces key content. Let’s take a look at how he achieves each of these results.

First, we’ll examine the way Davis grabs the reader’s attention. The first two sentences of this introductory paragraph draw the reader in through descriptive language that allows the reader to visualize the Caribbean Sea. Without these sentences, we readers wouldn’t be engaged with the text in such a clear and effective way. Davis’ description of the “warm and clear” Caribbean Sea waters and his statement that “everything appears peaceful” appeal to the reader’s senses and allow a reader to envision him- or herself in this environment. Once the reader is able to picture him- or herself in this beautiful Caribbean Sea setting, Davis skillfully introduces the book’s content.

Figure 1.1 Key Actions Introductions Perform and Why they are Important

Figure 1.2 How the Introduction to Coral Reef Performs the Key Actions of an Introduction

In the third and fourth sentences of this paragraph, Davis transitions from language meant to engage readers to introductory information about the book’s content. The third sentence, “But just below, rising from the bottom of the sea, there is a very busy place” shifts the reader’s attention away from the water’s surface, while the fourth sentence focuses readers specifically on “the underwater community of the coral reef.” After reading this paragraph, the reader clearly understands that Davis’ book will focus on coral reefs. However, Davis’ introduction does more than simply say, “This text is about coral reefs”; it begins by drawing the reader in with an appealing sensory description of the Caribbean Sea and then transitions from that opening image to a specific mention of coral reefs, the book’s focal topic. Figure 1.2 highlights the features of this introduction, identifying the two key actions performed by introductions and which components of Davis’ text perform each of these actions (a blank, reproducible version of this chart that you can use in your classroom is included in the appendix).

In the next section, we’ll take a look inside a third-grade classroom where I helped students understand the importance of crafting an effective introduction.

A Classroom Snapshot

It’s a Wednesday morning, and the third graders I’m working with are absolutely humming with energy. They spill into the classroom and take their seats, looking up at the question I’ve written on the whiteboard: “How would informational texts be different without their introductions?”

This is my third class working with these students on the importance of introductions to informational writing. In our first meeting, I showed students examples of especially effective introductions in published informational texts. During our second meeting, I talked with the students about the key actions introductions perform, using charts such as those in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 to highlight the purposes of introductions and how published authors achieve those purposes in their works. Today, my students will be enhancing their understandings of the importance of effective introductions by considering how published informational texts would be different without their introductions. The goal of this lesson is to further increase students’ awareness of why well-crafted introductions are important components of strong informational texts.

I ask someone to read the day’s “Big Question” out loud, and a young lady in the front of the room quickly complies. After she reads the question, I explain that it represents the focus for the day’s work. “Today, we’ll work together to answer this question: ‘How would informational texts be different without their introductions?’ To figure this out, we’ll look together at an example of a published informational text. We’ll first look at this example as it was originally written—with its introductory paragraph—and then we’ll examine how it would look without this introductory paragraph. After we do this, we’ll come back to our Big Question of the day and think about how this published informational text would be different if it didn’t have its introduction.”

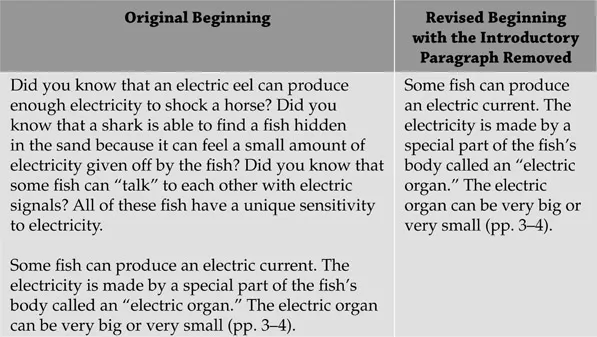

The students nod, and I direct their attention to a section of text from Caroline Arnold’s (1980) informational work, Electric Fish, which I’ve projected to the front of the room. The selection I share with the students, which contains the book’s opening paragraph and the first few sentences of the second paragraph, looks like this:

Did you know that an electric eel can produce enough electricity to shock a horse? Did you know that a shark is able to find a fish hidden in the sand because it can feel a small amount of electricity given off by the fish? Did you know that some fish can “talk” to each other with electric signals? All of these fish have a unique sensitivity to electricity.

Some fish can produce an electric current. The electricity is made by a special part of the fish’s body called an “electric organ.” The electric organ can be very big or very small. (pp. 3–4)

I read the passage out loud, asking the students to follow along. Once I’ve finished reading it, I ask the students what they noticed about the introduction: “What works about this introductory paragraph? Think back to our conversations about the key actions introductions perform.”

“It gets your attention,” responds one student, a young man seated at one of the back tables. “The questions at the beginning get you interested.”

“Yeah!” interjects another student. “Like the part about the eel being able to shock a horse. That got my attention. It would take a lot to shock a horse!”

“Great job, both of you,” I reply. “This introductory paragraph definitely grabs us and gets us to pay attention. Remember that we talked about introductions doing two key things—getting the reader’s attention and introducing key content, like the main information the book will discuss. Do you think this introductory paragraph introduces key content?”

Hand shoot up around the room. I call on a young lady, who explains, “I think it does. It talks about fish and electricity, and that’s what the book is about.”

“Very good point,” I respond. “This book is definitely about fish and electricity, and this opening paragraph clearly shows that. It introduces the key content that some fish have a unique sensitivity to electricity.”

“Now,” I continue, “I’m going to ask you to think about what the opening of this book, Electric Fish, would look like if it didn’t have its introductory paragraph.”

I place the chart in Figure 1.3 on the document camera so that the text projected to the front of the room now contains the original beginning of Electric Fish as well as a revised version of the beginning of the book without the introductory paragraph.

I read both versions out loud and ask the students to follow along silently as I do so. Once I finish, I ask the students to connect back to the day’s “Big Question” by considering the following question: “How is the beginning of Electric Fish different without its introductory paragraph?”

I call on a young lady who has quickly raised her hand. “The introductory paragraph gets you interested and shows what the book’s going to be about,” she explains. “The part on the right, without the [introductory] paragraph, doesn’t do those things. It just dives right in.”

Figure 1.3 Original Beginning of Electric Fish and a Revised Beginning with the Introductory Paragraph Removed

“That’s really well said,” I reply. “Without the introductory paragraph, this book just dives right in. The author doesn’t get a chance to grab our interest and introduce us to the topic like she does in the original version. So, how do you think informational texts would be different without their introductions?”

“Without the introduction,” answers a student, “the text would just start talking about the topic without getting us interested or showing us what the book is about. The introduction’s kind of like the beginning of a movie when they first show you the characters and what’s going on. The movie would be confusing if it didn’t have that beginning.”

I smile, thrilled with the student’s comparison: “Excellent connection—I love that comparison you made! Introductions are really important aspects of informational writing. All of you did a great job today of thinking about this. In our next class, we’ll work on crafting our own introductions to the informational texts that we’ll be writing.”

Recommendations for Teaching Students about Introducing a Topic

In this section, I describe a step-by-step instructional process to use when teaching students about introducing a topic in informational writing. The instructional steps I recommend are: 1) Show students examples of introductions from published informational texts; 2) Talk with students about the key actions introductions perform; 3) Ask students to consider how published informational texts would be different without their introductions; 4) Work with students as they craft their own introductions to informational texts; and 5) Help students reflect on why their introductions are important components of their informational writings. Each of these recommendations is described in detail in this section.

- Show students examples of introductions from published informational texts.

I view this mentor text use as the foundation of effective writing instruction. By showing our students examples of outstanding introductions, we are allowing them to learn about effective writing directly from expert informational authors. The examples featured in this chapter from Reptiles, Coral Reef, and Electric Fish are excellent models of introductions and can certainly be used successfully in many classes. However, I also recommend that you keep your students’ particular interests in mind when selecting mentor texts to share with them. I have found that when students interact with examples that align with their interests, they are especially likely to be receptive to instruction related to those examples. Once you’ve shown your students examples of effectively written introductions from published texts, you can think about the next step of this process: considering the key actions that introductions perform.

- 2. Talk with students about the key actions introductions perform.

This next step is firmly rooted in this book’s toolkit approach. Now that the students have seen examples of strong introductions, we teachers can talk with them about why introductions are important tools for effective writing. In order for students to understand the importance of a strongly written introduction to an exemplary piece of writing, they must understand the key functions of introductions: 1) Engage the reader; and 2) introduce key content. To help students understand these actions that introductions perform, I recommend beginning by showing them the chart depicted in Figure 1.1. This chart describes each of the actions introductions perform and explains why these actions are important.

Once you have discussed this chart with your students and you are comfortable with their understandings, talk with them about how a published text performs these functions. To do this, present your students with an introduction from a published work and ask them to comment on which sentences from the text are used to engage the reader and which are used to introduce key content. I recommend showing your students an example of your analysis of a text before asking them to do the same on their own. I like to show my students the information in Figure 1.2 so that they can see how I’ve divided the introduction of Gary Davis’ Coral Reef into these categories. Once I’ve discuss...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Meet the Author

- Acknowledgments

- List of eResources

- Introduction—“The Tools of Informational Writing”: Helping Students Understand the Relationship between Mentor Texts and Their Own Informational Writing

- Section 1: Informational Writing Strategies Aligned with the Common Core Standards for Grades 3–5

- Section 2: Putting It Together

- Section 3: Resources