![]() Part I

Part I

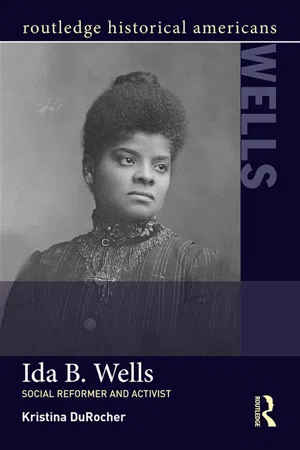

Ida B. Wells![]()

Introduction

“The way to Right Wrongs is to turn the Light of Truth upon Them.” Ida B. Wells 1

In 1883, Ida B. Wells, a twenty-one year-old black woman, boarded a train in Memphis, Tennessee to commute to her rural teaching job. On September 15, as on countless other days, she purchased her thirty-eight cent ticket and boarded the first-class car. A little under five feet tall, Wells wore a full-length dress covered by a linen duster with a hat and gloves. She carried a satchel, a newspaper, and a parasol, all trappings of a middle-class traveler.2 She later recalled in her autobiography that when the train was underway, the conductor, instead of collecting her ticket, “handed it back to me.” She remembered thinking to herself, “If he didn’t want the ticket I wouldn’t bother about it” and resumed reading her newspaper.3 The conductor continued gathering the remaining passengers’ tickets and then returned to her side, informing her that she had to transfer to the other train car. Surprised, Wells reminded the conductor that “the forward car was a smoker.”4

The smoker car, located directly behind the locomotive, was so-named for the debris and fumes that floated in from the coal-powered engine, making it a dirty, noisy space occupied primarily by male passengers of both races who could ride unencumbered by restrictions on smoking, drinking, or using coarse language. In contrast, the first-class car required passengers to observe a code of behavior in order to protect its respectable female passengers, leading to its common name, the “ladies” car. Wells, who had purchased a first-class ticket, refused to leave her seat and relocate to the smoker car, an inappropriate place for any reputable woman. While the exchange started out as a polite request, the encounter quickly escalated after she informed the conductor, “as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay,” prompting him to seize her baggage and proceed to the smoker car in an effort to compel her to follow.5 When she remained seated, he returned and grabbed her arm, endeavoring to drag her out of the car. Wells reacted by biting him on the back of his hand. When he drew back, she locked her feet under the seat in front of her to brace against any further efforts to remove her. As “he had already been badly bitten,” the conductor retreated. He soon returned, accompanied by a baggage worker, and both men seized Wells. At this point, one may wonder about the other train-car inhabitants. What did they think of the employees manhandling a well-dressed teacher? In response to her struggle, the white women and men in the car repositioned themselves in order to gain a better view. “Some of them,” Wells recalled, “even stood on the seats” and applauded the men for their efforts.6

After the employees bodily removed her from the first-class compartment, Wells declared that she would rather “get off the train” than ride in the smoker car. To the two Chesapeake, Ohio, Southwestern Railroad Company attendants, this was an acceptable option. When the train paused, Wells disembarked. Although she had not been physically hurt during the confrontation, the men’s rough handling had torn her clothing.7 On the side of the tracks, still clutching her train ticket in her hand, she determined to fight her treatment. After returning to Memphis, she contacted an African American lawyer who attended her church, Thomas Cassells, and initiated a lawsuit using an 1881 Tennessee state law requiring separate first-class accommodations for each race as the basis for her case.8

Wells’s legal complaint was just the beginning of her lifelong dedication to determinedly and vocally fight for social justice in every place she encountered inequality. Wells’s lawsuit introduced her to the world of newspaper publishing, where she shared her perspective on the myriad issues facing African Americans and women, and as her point of view gained widespread recognition she earned the designation of “Princess of the Press.” An experience with racial violence led her to confront the emerging system of white supremacy in the South, and she single-handedly launched an international campaign that revealed the motives behind the increasingly widespread practice of lynching. Despite threats of deadly violence, she continued to spread her message by publishing her findings and publically lecturing across the nation and in England.

Her reform work gained her allies in Frederick Douglass, Jane Addams, and William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, while she publically opposed Booker T. Washington and temperance leader Frances Willard. She founded and participated in numerous organizations to combat social disparity and organize for political power. She created the Alpha Suffrage Club to advocate for black women’s right to vote and participated in the national women’s suffrage movement. She established the Negro Fellowship League to educate and support urban black men and fight issues of poverty in Chicago, and was among the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She started the first black kindergarten, fought several legal battles for the fair treatment of African Americans within the judicial system, and became the first black female probation officer in Chicago, applying her salary to support these efforts.

Wells returned to her journalistic roots in the early twentieth century, investigating and publishing tracts on race riots in Missouri, Illinois, and Arkansas. Her protests against the government’s treatment of black soldiers during World War I earned her a visit from the Secret Service and the label of a “subversive.”9 Undaunted, Wells enlisted black women to participate in politics during the 1920s, when Prohibition, corruption, and mobsters made such attempts a precarious enterprise. In 1930, she ran for an Illinois State Senate and lost, but this defeat only increased her resolve. Unfortunately, she died from kidney failure the following year. During her life, Wells, as a black middle-class woman, participated in almost every major social reform movement from 1880 to 1930 at the local, regional, or national level.

Wells lived in a rapidly evolving world, and the racial, gendered, sexual, and political mores shifted greatly during her lifetime. Her story is of a woman in the front lines of a society facing the challenges of a modern world, one that contained massive inequalities she fought to correct. Wells recognized, however, that her battles were part of a larger war. She began the last chapter of her unfinished autobiography with the words, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty,” quoting Wendell Phillips’s 1852 speech to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Phillips, an abolitionist, told his audience, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty; power is ever stealing from the many to the few.” To prevent an unequal balance of power, the orator continued, required “continued oversight” and “unintermitted [sic] agitation” lest “liberty be smothered.”10 Using his words, Wells connected her attempts to Phillips, and her efforts for social equality as a fight for liberty. She believed that social change required agitation and that every right gained needed protection, lest those in power usurp it. Wells committed herself to these pursuits, and with these words, reminded her readers of the need to be ever vigilant in ensuring that civil liberties apply equally to all in order to end social injustice.11

Notes

![]()

Chapter 1

Establishing Citizenship, 1862–87

Ida Bell Wells was born into slavery in the midst of the Civil War on July 16, 1862. Her mother, Lizzie (Elizabeth), and father, Jim (James), lived in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Two weeks prior to her birth, the Union and Confederacy fought near the town, which changed hands between the two armies at least fifty-seven times.1 Later that fall, Union General Ulysses S. Grant made Holly Springs his headquarters as he prepared for the Vicksburg Campaign. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, freeing all slaves residing in the rebelling states, and although many African Americans sought liberation by escaping to the Union lines, Lizzie and Jim did not. With a young baby, they were perhaps unable or unwilling to leave Mississippi.2

Holly Springs, the seat of Marshall County, grew rapidly during the antebellum period due to its ideal location for growing cotton.3 In 1840, the census for Holly Springs recorded 9,276 white residents, a number that more than tripled by 1860 to approximately 29,000. The slave population also grew rapidly between 1840 and 1860 from 8,260 to 17,439.4 Correspondingly, vast plantations spread across the countryside and, in 1860, just before the Civil War, Marshall County produced 49,348 bales of cotton, the most of any county in the nation.5 One of the slaves among this increasing populace was Ida’s father Jim, born near Holly Springs, the child of his African American mother, Peggy, and Morgan Wells, the white master of the plantation. Jim, a mulatto, or person of mixed race, inheri...