This is a test

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Narrative Architecture explores the postmodern concept of narrative architecture from four perspectives: thinking, imagining, educating, and designing, to give you an original view on our postmodern era and architectural culture. Authors Sylvain De Bleeckere and Sebastiaan Gerards outline the ideas of thinkers, such as Edmund Husserl, Paul Ricoeur, Emmanuel Levinas, and Peter Sloterdijk, and explore important work of famous architects, such as Daniel Libeskind and Frank Gehry, as well as rather underestimated architects like Günter Behnisch and Sep Ruf. With more than 100 black and white images this book will help you to adopt the design method in your own work.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Narrative Architecture by Sylvain De Bleeckere, Sebastiaan Gerards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THINKING

At first sight, it’s not so difficult to ascertain that the architect thinks. Take a look around the architecture bookshop. On the shelves, you can find books written by architects. Some famous postmodern architects even started their career by writing books on architecture. The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas is one of them. Born in 1944 and co-founder of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in 1975, he found his way into the world of architecture by writing his influential book Delirious New York (1978).

In his book he tells the story of Manhattan, New York, from a new point of view. Koolhaas was known as a thinker before becoming a designer of real buildings (Dutch Dance Theatre in Rotterdam, 1984–1987), and he demonstrates in his book that the metropolitan city of Manhattan originated from a special and unique way of thinking. The city plan, the ensemble of buildings, they all had their roots in a certain philosophy which Koolhaas articulates in his book. In a historic picture of Robert Moses, the most influential city planner of Manhattan, we see how the man is thinking while looking at a scale model of the future Manhattan. In the same way, Koolhaas is a reflecting architect. On the occasion of his doctorate honoris causa, bestowed upon him in 2007 by the rector of the University of Leuven, he presented himself not as an architect, but as a thinker. He repeated that statement when he was interviewed by Margot Vanderstraeten in 2013 for the Dutch newspaper De Morgen.

Writing, expressing myself in language, for me that’s thinking. It’s trying to understand, to formulate what is happening. I need this form of consciousness. I needed it as a young architect. By writing, I created room for myself to become an architect.(Vanderstraeten 2013, 14)

Confronted with the building policy in his own country, Japan, architect Toyo Ito expressed his deep concern about the role of architecture in 2016: ‘To strengthen people, we need to create a new way of thinking, a new era. If we don’t succeed in realizing this, the things we build will never make people happy’ (Ito 2016, 52).

Along with Koolhaas and Ito, we can ask, what is the story of thinking in our postmodern era in relation to the designer’s story? Is there a story to tell? We see a very inspiring story about thinking as an important stepping-stone for the postmodern designer looking, like Ito, towards the future. Our story opens with a visit to three houses.

The Narrative of Architecture

Three Houses

We start our story about thinking and architecture with three houses in three different continents. The first one is located in Belgium. House AST 77 is situated in the small Flemish city of Tienen, in a row-house street, a typology that marks the Flemish architectural landscape (Figure 1.1). We find the second house in Tokyo, Japan. The White U house is a design by Toyo Ito, the architect who won the 2013 Pritzker Price (Figure 1.2). We visit the third house in Brentwood, Los Angeles, California. It’s the Rodes House for which Moore Ruble Yudell was awarded the 1981 Architectural Record House of the Year (Figure 1.3).

When we look at these three houses, we see how much they differ. They all tell us about their distinctive cultures: a Belgian house, especially the Flemish terraced house, distinguishes itself by its openness to the street, while the other row houses rather appose themselves to the street, the Japanese one with its need for finding a peaceful place in a stressful life in the metropolis, and the Californian one with its specific sense for theatre. These three houses have a contrasting appearance: House AST 77 with its glass front, the concrete White U with its striking shape which looks very modern, while the Rodes House is known as a postmodern icon.

FIGURE 1.1 House AST 77 (Tienen, Belgium). Photo: © Steven Massart.

FIGURE 1.2 White U (Tokyo, Japan), Toyo Ito. Photo: © Office Toyo Ito and Associates.

FIGURE 1.3 Rodes House (Brentwood, Los Angeles, CA, USA), Moore Ruble Yudell. Photo: © Sylvain De Bleeckere.

Despite their differences, the houses have one important thing in common. They tell us about the phenomenon of housing. While designing the houses, each architect has thought about the far-reaching meaning of housing in human life generally and in the daily life of the inhabitants in particular. We owe our appreciation of that kind of thinking to the relatively recent movement in Western thinking, called phenomenology. Here, at the beginning of our story on thinking, we meet our main character, the phenomenon. It was created by Edmund Husserl, the founding father of what is now well known as the phenomenological movement.

The School of Athens

Our human species didn’t have to wait until Husserl to discover the importance of thinking. The Italian grandmaster of the High Renaissance, Raphael, knew that. He remembered and honoured the famous philosophers of ancient Greece in one of his admired Vatican frescoes, The School of Athens. Around the two main figures, Plato and Aristotle, Raphael painted an ensemble of different generations of pioneers of Western thought. The Italian master used the Western and modern technique of perspective, analysed and demonstrated for the first time by architect Filippo Brunelleschi. In his one-point perspective mural, Raphael located his ancient thinkers in the utopian scene of a future Athens. This was his prelude to the utopian ideas of modern architecture (Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4 The School of Athens (Vatican, Rome, Italy), Raphael.

The introduction of the phenomenon in the domain of thinking by Husserl in the twentieth century originated in the critical rejection of modern thinking in its most orthodox praxis. In the first half of the twentieth century, Husserl saw how modern thinking was practiced in the process of modernization of the whole of Western culture since the Enlightenment. We find the announcement of that process in Raphael’s mural. In this mural we can see a vision of the coming of the modern movement, which elaborated the ancient Greek marveling over humans’ capacity to think. In his mural the Italian painter demonstrated the new intellectual enthusiasm for the renewed belief in the power of human thinking as the great source for the creation of a new utopian world by and for humanity itself.

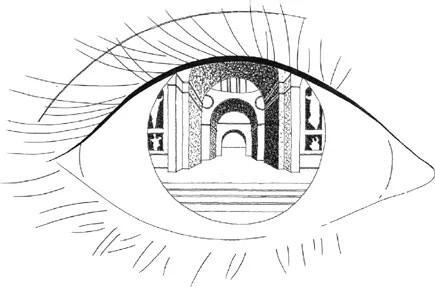

In the one-point perspective, we can see how the power of human thinking became paradigmatic. Our sketch shows the typical logic of the modern practice of thinking (Figure 1.5). The big eye represents the human mind, the cornerstone of modern thinking. In ancient cultures, the mind was already seen as ‘the third eye’. And still in Christian culture God’s mind appears as one eye in a triangle, as can be seen on the American one dollar bill. The Indo-European languages also show how the meanings of the words ‘mind’ and ‘eye’ are closely related. The term ‘world view’ or ‘world vision’ clearly demonstrates this. It means opinion, the way of seeing things, the way of thinking.

FIGURE 1.5 The Third Eye. Sketch: © Femke Clerkx.

The Thinking I

In our sketch, the big eye symbolizes the modern belief in thinking as a substance. The name for that substance is the Latin ratio, the English or French reason or raison. No one defined it better than the French philosopher and one of the founders of the modern school of mathematics in the first half of the sixteenth century, René Descartes, who came up with the modern vision on reason. He worked out the most famous formula of modern thinking: ‘Cogito ergo sum’, in English translated as ‘I think, therefore I am’. The moderns called the substance of thinking the I, the mental instance which can prove its existence by saying I. That means that the substance is self-conscious and knows its own existence. The ‘I says I’ awakens the power of reason, proclaiming its own autonomous existence in the world. From that position it opposes the world. The self-conscious I is clear, straightforward thinking: reason and pure reason only without any interference. The products of that untroubled thinking are clear ideas, logically connected and deeply rooted in the rational power of the I. That modern ratio proclaims the status of absolute assuredness for its self-built-up knowledge. That ratio creates the one-point perspective, as seen in our sketch. From the I, the open and clear eye, starts the rational design of the world that it wants to shape and realize. Its design doesn’t relate to the existing world, but to a utopian world instead. This modern eagerness to create its own utopia was already at work in Raphael’s vision of the new Athens which would rise from Renaissance thinking.

Our sketch shows the subject-object structure which typifies modern thinking. On this side of the perspective, we find rational thinking, the modern I or subject, as the dominating substance. It acts as the stage manager of the scene. It enthrones its own autonomy. It prepends itself as the self-reliant substance and independent subject. On the other side of our image, the self-created new rational world is standing. The modern I wants to create its own utopia as an image of its own rational power.

Hilberseimer’s Radical Praxis of Thinking and Designing

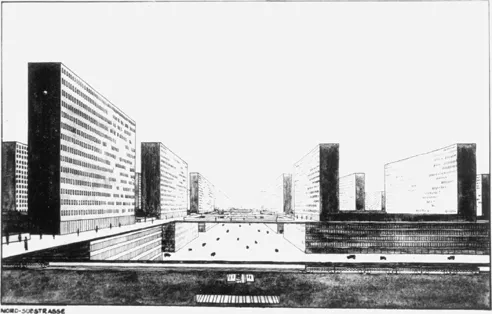

To better understand what this modern strategy of thinking implies and why phenomenology is opposed to it, the seminal design of the utopian metropolis of Ludwig Hilberseimer is very apt. Hilberseimer was a German-born American architect, urban planner and theoretician who taught at the famous Bauhaus until he fled Nazi Germany in 1938 for Chicago. There, he became head of urban planning at IIT College of Architecture and director of Chicago’s city planning office. He was also a member of the thinktank of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne), a movement of radical modern thinking in architecture and urban design during the 1920s and 1930s. He was foremost a thinker and one of the pioneers of the discipline which is nowadays called urban design.

Hilberseimer presented his utopian design in his book Großstadtarchitektur (1927), the full English translation of which only appeared in 2012, under the title Metropolisarchitecture. In his famous sketches in the book, Hilberseimer practices modern thinking with its one-point perspective in the domain of architecture and urban planning (Figure 1.6). With his design he erased the existing world and wanted to create an entirely new urban environment for future mankind living in megacities. Ever since, Hilberseimer’s images have belonged to the narrative of metropolis. Pier Vittorio Aureli, the present-day Italian architect who mainly practices architecture as a thinker, notes that ‘these two images have been used so often to represent the horror of the modern metropolis that they have become clichés, especially because they are often considered only as images and not as illustrations of a precise urban proposal’ (Aureli 2013, 334).

FIGURE 1.6 Metropolisarchitecture. Sketch: Ludwig Hilberseimer. © The Art Institute of Chicago.

We support Aureli’s rediscovery of Hilberseimer as a protagonist in the movement of modern architecture, but we dispute his interpretation of Hilberseimer’s sketches. They are not just images, not even illustrations. They are instead real expressions of the modern will to thoroughly reshape the human habitat. Modern thinking in its purest form here becomes architecture as a thinking praxis. Architectural design becomes a research praxis in the human and social domain. In the words of Hilberseimer himself: ‘The chaos of the contemporary metropolis can only be confronted with experiments in theoretical demonstration’ (Hilberseimer 2013, 112).

Directly in line with Descartes’ rational ego, Hilberseimer explores this new way of thinking in the field of the human urban habitat. Fully in accordance with that modern logic the existing urban reality has no value whatsoever for Hilberseimer. This can be seen in his thinking sketches. We do not see any kind of heritage building or any kind of already existing greenspace integrated in the design. In point of fact Hilberseimer designed his urban utopia from practicing modern thinking in its most radical mold. Hilberseimer writes in his essay The Will to Architecture: ‘Rational thinking, accuracy, precision, and economy – until now characteristics of the engineer – must become the basis of this comprehensive architecture’ (ibid., 284). As his English translator comments, Hilberseimer introduced ‘the primitive, productive architecture’, ‘in its elemental, geometric rigor’ (Anderson 2013, 31, 33). Hilberseimer’s own words confirm that ‘elemental’ thinking: ‘Architectural design must be conscious of the fundamental elements of all design’ (Hilberseimer 2013, 283). Architecture design must act autonomously, it must evade every sparkle of subjectivity. Here it becomes clear how the modern ratio, as the I proclaiming its own existence, really performs....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Setting the Scene

- 1 Thinking

- 2 Imagining

- 3 Educating

- 4 Designing

- Open-Ended Stories

- Index