![]()

Part One

A call for change

We ask:

1 That to aim towards one planet living should become an underlying principle of planning and official policy as de facto the only objectively verifiable sustainable strategy.

2 That the same set of social and environmental criteria should be used to assess all planning applications to create a level playing field.

3 That these criteria, amongst others, should be informed by ecological footprint analysis, which enables all projects to be compared for their environmental impact.

4 That official attitudes to land use should change to help rural areas use one planet living methods to become more productive and more populated, and urban areas more green.

We make this call for the following reasons, which we substantiate below:

The One Planet Life

1 Results in more productive land use, with far fewer environmental impacts.

2 Creates more employment than conventional agriculture.

3 Promotes greater physical and mental health and well-being, reducing the burden on the welfare state and health service.

4 Requires no agricultural subsidies, unlike some conventional farming.

5 Improves the local economy, resilience and food security.

6 Therefore is more sustainable and gives excellent value.

![]()

Just one. Obviously. But the way some people carry on you’d think we had five – in some cases even eight – wonderful blue, vibrant orbs just like planet Earth, rotating round our life-giving sun. Perhaps they imagine these worlds – duplicates of ours except minus human beings – are hiding on the far side of the sun. Sitting there conveniently, so that when we’ve used up all the resources on this planet, we can go and tap into those. How simple the future might be if we could. We’d probably need more than one extra planet. But hey, you never know what might turn up.

As far as I know, astronomers haven’t detected any more earth-like planets in the attainable vicinity.

What a shame.

The problem is, that with a human population projected to rise up to nine billion or so by 2050, we already use up more resources provided by the Earth’s land surface and bodies of water than are being naturally replaced. Coincidentally, I’m writing this on 20 August 2013, dubbed by the Global Footprint Network and the New Economics Foundation as ‘Earth Overshoot Day’1 for this calendar year. This marks the date when humanity as a whole has exhausted nature’s budget for the year, assuming we start each one with a fresh balance sheet. From this point on for the rest of the year, humanity is operating in overdraft, creating an ecological deficit by drawing down local resource stocks, polluting the land and seas, and accumulating carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The ecological footprint

We know this thanks to an amazing tool. Ecological footprint analysis is a resource-accounting tool that helps countries understand their ecological balance sheet and gives them the data necessary to manage their resources and secure their future. The unit used is global hectares (gha) per capita, that is to say the amount of average quality land area required to provide all the things we need as individuals, not to mention to absorb the pollution we create. It’s different for the inhabitants of different countries. It is also different for individuals depending upon their way of life. While it’s true that there are concerns2 about the accuracy of some of the tool’s assumptions (for example, the scoring may need tweaking for different types of land-use) there’s no denying its general message. Moreover, the methodology behind the numbers is being constantly improved.

The most recent data is from 2010.3 In that year, the USA had the highest footprint in the world: 8 gha per capita; but it has a biological carrying capacity of 3.9 gha per individual. This gives it a deficit of 4.1 gha per individual. In other words, Americans are using over twice as much as they can sustainably manage. The United Kingdom has an average ecological footprint of 4.9 hectares, with a biocapacity of 1.3 ha. In other words, British citizens are using more than three and a half times what they can sustainably manage.

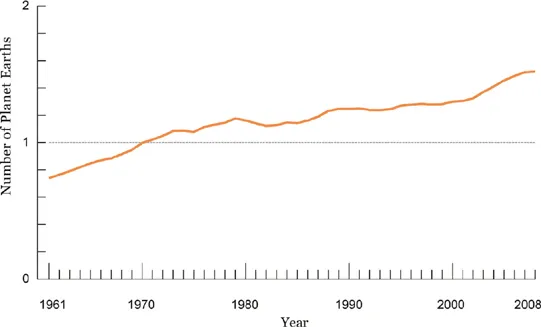

Figure 1.1 The world’s ecological footprint since 1961. This is an average amount for every person on the planet. It increases because the population is increasing. As many people consume few resources, it means that the ecological footprint of the middle class and rich, of whom there are more and more, especially in the fast-growing developing countries, is outweighing the 20 per cent of the world’s population who live in extreme poverty (under $1.25 per day).

Source: Global Footprint Network, 2011.

Another way of getting your head around this is to divide up the useful land area of average quality that we use on the planet by the population level. Doing this gives an average area of land for each individual of 1.8 ha. But we are using collectively, on average, more than twice as much as this. So, again on average, we are behaving as if we had at least one more planet like this one.

The financial crash of 2008 occurred because banks were lending more than they were receiving and people were borrowing more than they could pay back. This is exactly what’s happening now with our global resource use. A potential future ecological crash promises to be much worse than the economic shock of 2008. Because, unless we consume a great deal less and recycle or reuse a lot more raw materials, there’s no way we can pay back what we’ve taken. Just pause for a moment and imagine the consequences of this: refugees, starvation, violence, wars and even more food banks; and the poor will suffer the most.

At least we understand that what we borrow from banks we will have to pay back some day – with interest. We still do not get it, that we borrow – not take – from the natural world. The Global Footprint Network4 – one of the organisations that works out ecologicial footprinting – believes us to be on track to require the resources of two planets well before mid-century. Actually, I think this is a severe underestimate, and Fred Pearce, the environmental correspondent of the New Scientist magazine, agrees.5

So: the future will be sustainable or not at all. This truism implies that humanity as a whole will have to learn to live within its means, otherwise millions – perhaps billions – of us will not be able to survive at all.

This is where the idea of The One Planet Life comes from. We all have to be able to live within the planet’s means while affording a good standard of living for everyone. So if we are to lift out of extreme poverty the 1.2 billion people who currently live on under $1.25 per day, the rich will have to consume less, and the way everyone lives will have to change.

This process of change will work on several levels: individuals can reduce their own ecological impacts, using the ideas in this book; businesses, in particular industries, can move towards ‘closed-loop’ resource use and net zero fossil-fuelled energy use (using a combination of renewable energy, energy efficiency and carbon offsetting); and governments, whether national, regional or local, can use their legislative and planning powers to support healthier and more sustainable ways of life for their citizens: to make it easier for them to live the One Planet Life.

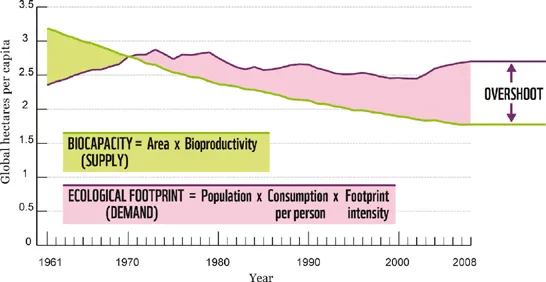

Figure 1.2 The overshoot of the capacity of the world’s biological systems to accommodate the consumption levels of humanity is increasing. The pink area shows the environmental deficit.

Credit: Global Footprint Network, 2011.

The components of the ecological footprint that these governments at every level are able to influence concern things like: the energy performance standards of buildings; the carbon content of energy; the treatment of waste using the Waste Hierarchy (see Chapter 3); managing water catchments better; the provision of subsidised public transport that people want to use; making urban areas walkable and cycle-able and combating car dependency; situating housing near to jobs and shops, schools and hospitals; incorporating nature in cities; preventing pollution; and encouraging the growing of food within and near to the places where it is consumed.

The good news is that things like this are already happening in many places around the world. Some examples are given towards the end of this book. One country has even begun explicitly to use the ecological footprint as a planning tool. That country is Wales, a part of the UK that has jurisdiction only over some of its policy areas and no tax-raising powers. It has chosen the measure of the ecological footprint to help it determine whether some activities are in line with its constitutional aim of securing sustainable development. It has adopted a Sustainable Development Scheme, called ‘One Wales: One Planet’, that includes an objective that: ‘within the lifetime of a generation, Wales should use only its fair share of the earth’s resources, and our ecological footprint be reduced to the global average availability of resources – 1.88 global hectares per person in 2003’.6 In 2006 the ecological footprint for each Welsh citizen was 4.41 global hectares.

The golden thread

‘Sustainable development is a golden thread that winds its way through all that we do’, asserted the civil servant in charge of planning policy in the Welsh Government, in conversation with me in his office in Cathays Park, Cardiff, in September 2013.7 Although these words echo strongly those of the UK government’s National Planning Policy Framework (cited by Communities Secretary Eric Pickles, see below) I do believe he wasn’t being cynical, and that there is a genuine commitment to sustainable development in Wales, even though it is not yet clear what this will mean in practice. This is being embedded in something called a Future Generations (Wales) Bill which, at the time this book went to press, was in the consultation stage. It’s the name the government has given to its bill for advancing sustainable development, because they think that by placing the emphasis upon children a...