![]()

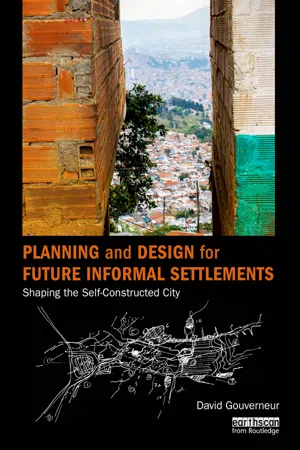

Figure 1.1: 23 de Enero Housing Project surrounded by informal settlements, Caracas, Venezuela

Attempts to deal with the urbanization challenges of the developing world

Shelter is a fundamental human right; it is one of the essential factors of satisfactory living conditions and it is the principal built component of all cities. In most developing countries, the conventional methods for accommodating housing and urban demands of the poor are inadequate. In many cases, urban planning and design paradigms exclude the poor from appropriate sites, denying them the benefits of infrastructure, services, and amenities. Usually, these new urban dwellers cannot take advantage of the financial mechanisms of subsidized social housing programs; simultaneously, the production of public housing simply cannot cope with the demand.

Although urban decision makers and stakeholders are biased against informal development, it has become necessary to consider how political, academic, professional, and institutional efforts have tried to address the challenges of informal urbanization. This reflection reveals that the twenty-first century lacks an effective model to encompass the magnitude and complexity of ongoing urbanization in developing countries.

This chapter is structured in seven sections. The first section presents preconceptions that stakeholders have about informal settlements. It also highlights how important it is to ensure that those who have the vision, resources, managerial skills, and the will to act understand what is at stake. The second section explores what the role of city planning and urban design has been in the context of informal urbanization. It aims to better capture how Informal Armatures can transform city planning and urban design. The third section describes what could be considered the limited impact of social housing programs. The fourth section analyzes the contributions and limitations of the programs referred to as “Sites and Services” as urban frameworks for self-constructed neighborhoods. A review of the different approaches, in Sections 1.5 and 1.6, indicates that all of these models have not been able to encompass the magnitude and complexities of ongoing urbanization in developing countries, especially in light of the scale of informal urbanization and worldwide environmental challenges. Section 1.7, then, suggests that the Informal Armatures approach may offer a new way forward.

Figure 1.2: Improved informal settlement of El Risco de San Nicolás, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands

1.1 Biases against informality

Informal settlements in developing countries are the by-products of the rapid urbanization driven by the economic and political changes associated with industrialization and globalization.1 In economically developing countries, the shift from predominantly rural populations to highly urbanized populations is similar Urbanization in the developing world to the transformation already experienced by today’s more developed nations. Among the differences are the currently unprecedented growth rate, and the global scale of economic and environmental impact. Informal settlements are generally the result of internal and external migratory trends, rapid increases of population within urban centers, and the financial and administrative inability to provide adequate land, infrastructure, services, and housing to the poorest segments of the population.

Informal settlements are often perceived as a threat by the formal urbanites that openly manifest their desire for informal neighborhoods to be eradicated. In many cases, inhabitants of the formal city assume that those who live in informal neighborhoods have different cultural values and behavioral patterns. They associate informal neighborhoods with poverty, violence, drugs, and unhealthy living conditions. However, this perception of informal settlements and their inhabitants is often distorted, as both groups socialize on a daily basis on the formal turf as fellow citizens. While there are certainly morphological and performative conditions that separate these worlds, cultural and mental barriers are even stronger factors. Formal residents rarely have access to the informal areas; therefore, uncertainty helps to stigmatize these settlements. There are clear reasons for this lack of contact, such as the concern for safety, the absence of roads and transportation, and the dearth of amenities and public spaces.

The wealthy and educated classes in developing countries often identify with the urban value systems of former colonial rulers or with foreign models that were adopted throughout the developed world during the twentieth century. These practices are reflected in the institutional, legal, and design frameworks of post-colonial cities and are crystallized in the built results of planning and zoning efforts. However, they are very different from the logic embedded in the construction of informal settlements,

In Colonialism and Underdevelopment in Latin America (2009), Valentin and Raduan argue that although colonialism was an undeniable part of the historical process and formation of some societies, its legacy led to social stratification and extreme social inequality. They point out, “The discrimination and oppression present in those hierarchical societies are the main inheritance of the former colonies and are a persistent tragedy, being part of the unsolved questions of the recent past.”2

Colonial enterprises usually exercise territorial, economic, political, and social control through town and city planning. The colonial urban–rural models Urbanization in the developing world frequently reflect the conditions of the imperial centers, or new urban prototypes are created to facilitate the economic exploitation of acquired territories. Such models derive from the urban and agricultural systems embedded in the colonizer’s culture but evolve to accommodate local conditions, eventually creating hybrid models of occupation. The effects of these colonial formations were noticed in the first half of the twentieth century. For example, in a 2006 study on the Spanish colonial period in Latin America, Urbanismo Europeo en Caracas (1870–1940), Arturo Almandoz pointed out that in 1944 Francis Violich first referred to this effect as “Old World-like” in his 1944 publication of Cities of Latin America. Housing and Planning to the South.3 As colonization advanced, local populations adapted to new territorial and urban patterns, or were forced out or willingly migrated to peripheral areas where they continued to live as they did prior to colonial occupation. Regardless of the degree of hybridization during colonial occupation, the newly imposed models resulted in the erosion or destruction of the indigenous forms of territorial occupation and culture.

In Spanish America for instance, the independence of the colonies brought on a reshuffling of power within the new nations with the introduction of legal, institutional, economic, and social reforms. But urban and architectural patterns after independence remained essentially unaltered. Frequently, the former colonizers were replaced by powerful, wealthy groups of the local population. They still adhered to the urban and cultural patterns of the deposed colonizers, maintaining marginalized groups in the same conditions of economic disadvantage and spatial exclusion.

Marginalized groups in these societies often share some of the values of the more affluent and/or educated people, but are strongly influenced by cultural patterns that stem from pre-colonial customs and recent rural origins or from other cultural contributions that enriched the cultural palette during colonial times. Residents of informal areas frequently voice their complaints against living conditions within their settlements, aspiring to achieve standards closer to those found in the formal sector. However, they rarely say that their ultimate goal is to move out, because they consider that their homes and neighborhoods can be gradually improved. While there may literally be no option for the poor to leave newly established informal settlements, there is often no will to do so, as emotional and social bonds flourish in their self-constructed environments.

This description might appear as an oversimplification of the social and ethnic milieu that is common to many developing countries in which different groups Urbanization in the developing world intermingle and share an ample body of continuously evolving hybridized cultural aspects. In Hybrid Identities (2008), Keri E. Iyall Smith and Patricia Leavy describe the complexity of cultural diversity as a living process in constant transformation influenced not only by ethnic or social diversity, but also by new technologies and evolving ecologies.4 In this regard, hybrid identities allow for the perpetuation of the local in the context of the global, a perspective that could allow the Informal Armatures concept to engage a wider range of communities by providing both specificity in the role of the components and flexibility of physical implementation.Informal Armatures address this hybrid cultural condition in order to facilitate solutions that will connect the formal with the informal logic in a mutually beneficial scenario.

The changing attitude towards informality varies from country to country but tends to travel a similar path. It is preceded by an initial period in which institutions and formal dwellers begin to understand that a new modality of informal occupation is beginning to occur, at which point they may ignore it or attempt to stop it through use of force or through developing formal housing provisions.5 While some nations today deal with informal growth in a proactive and creative way, others believe that they can control it and eradicate it. A recent example of the eradication of informal areas with no intention to relocate them occurred in 2008 in Harare, Zimbabwe, which resulted in the forced displacement of over 800,000 inhabitants who had invested years in improving their self-constructed districts. The National Government felt that these settlements were encroaching on areas that had potential for formal development and that they were an obstacle for marketing this city as a progressive and competitive African capital.6 Most of the displaced fled to other countries, mainly neighboring South Africa, some returned to their places of origin in Zimbabwe, and others initiated new informal settlements in more peripheral locations.

A second phase is one in which it becomes evident that the growth of informal settlements cannot be halted; the initial phase of resistance is followed by a period of acceptance, recognizing that informal settlements will become a permanent component of the city. During this period some actions are taken to prevent further informal growth on sites considered highly sensitive, such as those that may affect middle- and upper-income areas or that have significant potential real-estate value, allowing squatting on areas not targeted by the official plans for urbanization. Also during this phase, some forms of political support and institutional assistance are offered, providing the settlements with water, electricity, paved roads, Urbanization in the developing world and pedestrian paths, as well as basic community, educational, health, recreational, and daycare facilities.

Such acceptance became evident in the case of Caracas, Venezuela. Until the 1990s, the National Government and municipal authorities, mainly during pre-election periods, would carry out only minor interventions in the informal settlements, known as barrios, which were typically located on steep topography. These would be limited to paving pedestrian paths and stairways, channeling rainwater runoff or covering polluted streams, introducing simple forms of street lighting, and applying paint to unfinished brick building facades. In some cases, local health, educational, and sports facilities were also introduced. None of these interventions made significant changes to the quality of life within such poor communities; rather they would continue to be physically and functionally segregated from the formal city.

In most developing countries, the population living in informal settlements may equal or surpass the population living in formal settlements, so that it may becom...