This is a test

- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Architecture and Agriculture: A Rural Design Guide presents architectural guidelines for buildings designed and constructed in rural landscapes by emphasizing their connections with function, culture, climate, and place. Following on from the author's first book Rural Design, the book discusses in detail the buildings that humans construct in support of agriculture. By examining case studies from around the world including Australia, China, Japan, Norway, Poland, Japan, Portugal, North America, Africa and the Southeast Asia it informs readers about the potentials, opportunities, and values of rural architecture, and how they have been developed to create sustainable landscapes and sustainable buildings for rapidly changing rural futures.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Architecture and Agriculture by Dewey Thorbeck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

I like to have a man’s knowledge comprehend more than one class of topics, one row of shelves. I like a man who likes to see a fine barn as well as a good tragedy.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (American essayist and poet, 1803–1882)

Today it is your imagination I am speaking to and in order to provoke your imagination it is imperative that we suspend ourselves from the normal encumbrances that we use to anchor ourselves into our everyday comfort, into relationships, into identity and society. It is your inner self that I seek to engage in this conversation.

Kerry Arabena (Australian Professor of Public Health)

Architecture and agriculture has existed ever since humans first developed skills to grow plants and raise animals for food and fiber. With these skills they became rooted in one place, started to live and work with nature and constructed shelters for themselves and their animals as protection from the elements and for storage. It began a new relationship between humans, animals, and the landscape. No longer having to constantly move around to forage for food, human settlement emerged out of this new way of life and architecture began. It is the architecture of agriculture that is the subject of this book along with its connections to rural design, rural land-uses, and rural landscapes – historically, today, and in the future.

In America a number of historic barns and farmsteads are on the National Register of Historic Places and some are listed as National Landmarks, but when they are it often has more to do with the accomplishments of the farmer than with the architecture. Working buildings in the rural landscape have rarely been discussed by architectural historians other than in vernacular terms referencing historic building types or styles, yet these buildings are an integral aspect of the beautiful agrarian landscapes in America and around the world. Some of the best books on vernacular architecture that go beyond simply showing pictures by describing working buildings and other structures and landscaping constructed by people living in rural ecosystems include: Barn: The Art of a Working Building by E. Endersby, A. Greenwood and D. Larkin (1992); Barns of New York by C. Falk (2012); and the comprehensive Vernacular Architecture: Towards a Sustainable Future by C. Mileto, F. Vegas. L.G. Soriano, and V. Cristini (2014).

What is it about rural landscapes and the farmsteads, farm animals and fields that make them so interesting? Perhaps it is the nostalgic connection to our agrarian past where the making of architecture was directly connected to place, growing food, and the rituals of life – human, animal, and environmental. Rural architecture that has a strong relationship and fit with culture, climate, and place resonates with us because this connection is part of our human heritage. America was settled by immigrants and most were farmers who worked the landscape and melded with other farmers, creating the unique character of small towns and farm buildings in the American rural landscape that we love.

The small rural towns in America that developed along with agriculture were often located along roadways a distance apart (approximately 12–16 miles) so that a farmer could milk his cows in the early morning and travel by horse and buggy to town for supplies and home again for the evening milking. As these towns developed important public buildings like schools and courthouses were designed and constructed to reflect permanence. The most important of these was the county courthouse in the county seat, and they often adopted historical classical architectural styles as the model to portray permanence and the city and county’s intentions to be around for a long time. Many rural towns had a city square as the focal point and center of activities, with important buildings surrounding it or in some cases in it.

As my wife and I travel around the world we visit many rural places and have observed the similarity of how rural people have worked the land to provide the necessities of life. The scale and character might be much different in rural America with 400 years of agricultural experience than rural China with 5,000 years, yet each has developed its own unique culture, language, social organizations, and traditions based on their agricultural and economic systems, climate, and landscape. These agricultural systems around the world developed over time with indigenous techniques and practices based on human ingenuity respecting landscape, climate, and place while providing community food security in a way that conserved natural resources and biodiversity for the future.

The intention of this book, however, is to go beyond a picture-book view of the vernacular to begin a discourse about rural buildings and rural landscapes with the same critical eye that urban buildings in the urban landscape are looked at. My hope is that it stimulates readers to think about their own rural heritage and the importance of shaping sustainable rural futures for everyone including their own wellbeing and quality of life even if they live in a city. The book is also intended to help readers realize that urban and rural issues are interconnected, and that healthy and prosperous urban and rural futures require new understandings of our mutual connections and place on the planet.

In his book The Prodigious Builders (1977), author Bernard Rudofsky writes about architecture without architects as unorthodox architectural history while lamenting the ignoring of vernacular architecture by architectural historians. He goes on to describe American agriculture as being developed by immigrants who abandoned their cultural roots and became pioneers with no love for the land and the things that grew on it. He says this was

because the American frontier was a formidable obstacle to be conquered and that it wasn’t until the beginning of the 20th century that soil conservation was considered good for farming even as practices like contour plowing to prevent soil erosion had been in force in China for 5,000 years.

To Rudofsky, “What touches the heart is the mark left by the man who cultivates the land, and cultivates it wisely; who builds intelligently; who shapes his surrounding with a profound sense of affection rather than in the pursuit of profit.” It is this emotion that is at the soul of architecture and agriculture and the human spirit that I hope is conveyed in this book.

Rudofsky goes on to discuss the 1964 exhibition Architecture without Architects at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Vernacular architecture was not well recognized nor considered respectable at that time and he enlisted the support of a number of prominent architects and educators including Josep Lluís Sert, Gio Ponti, Kenzo Tange, and Richard Neutra, who were supportive. Walter Gropius had to be gently persuaded, but the tide turned when Pietro Belluschi, dean of architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote a letter to the president of the Guggenheim Foundation, where he said: “Somehow for the first time in my long career as an architect I had an exhilarating glimpse of architecture as a manifestation of the human spirit beyond style and fashion and more importantly, beyond the narrows of our Greek–Roman tradition” (Rudofsky 1977).

The Architecture Without Architects exhibition traveled around the world over an eleven-year time frame, ending when Rudofsky published The Prodigious Builders, which was his second book about vernacular architecture. Since that time no one has written as well about indigenous cultures and the human spirit shaping architecture and communities as he has done.

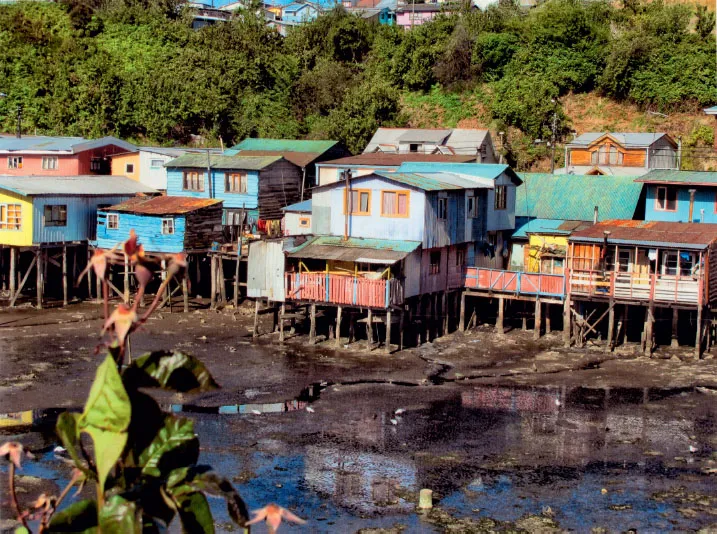

Rural and agricultural cultural heritage is now being recognized around the world by the United Nations as they declared some of these rural cultural areas as Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). They are defined by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN-FAO) as “Remarkable land use systems and landscapes which are rich in globally significant biological diversity evolving from the co-adaptation of a community with its environment and its needs and aspirations for sustainable development” (Koohafkan and Altieri 2011). How these rural cultural heritage sites are going to be authentically preserved is a major rural design issue that needs careful and sensitive analysis. There is much to be learned from the people living on these heritage sites for both new and renovated urban and rural developments in how to live on the land without destroying it. One of the designated GIAHS sites that illustrate this is the Chiloe Islands in Chile that have a unique and interesting culture of raising potatoes that evolved over time with nearly a thousand different varieties before the onset of agricultural modernization. This GIAHS is important for its genetic diversity providing a major social-economic service to the people who live and work in the group of islands (Figure 1.1).

Green design principles and design thinking might help political and governance entities worldwide to cross borders and engage with the diversity of peoples and their cultural, religious, and ethnic differences to make decisions about the land in a way that incorporates citizens into the planning process. If done sustainably it can help shape the urban and rural landscapes for a better future today without diminishing the opportunity for future generations to shape theirs. This means that any planning and design for future sustainable development needs to be accomplished on a bottom-up basis rather than the traditional top-down government approach. That is a rural design challenge that needs to be accomplished for both rural and urban futures.

1.1

The Chiloe Islands in Chile are a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System representing a land use system and landscape that is rich in globally significant biological diversity.

The Chiloe Islands in Chile are a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System representing a land use system and landscape that is rich in globally significant biological diversity.

Author’s background

To better understand my point of view about architecture and its connections to agriculture, and the goal of this book, here is a brief outline of my background. I grew up in the small rural town of Bagley in Clearwater County on the edge of the prairie in northwestern Minnesota and have admired barns and their animals ever since I first visited my immigrant Norwegian grandparents’ farmsteads. My mother’s parents, Olaf and Hilda Hanson, are shown in Figure 1.2 posing in front of their barn in the 1940s. Olaf emigrated from Norway through Canada to northwestern Minnesota in 1893 and settled in the river town of Thief River Falls in 1895. Shortly after he started to utilize his Norwegian boat-building skills, along with his father Olai, to construct steamboats on the Red Lake River, and began a career as a steam boat captain delivering supplies to early settlers along the river and Native Americans on the Red Lake Indian Reservation. He married Hilda Clemenson in 1901 and together they had twelve children including my mother, Emma, born in 1906. When the railroads were constructed the steamboat business declined, and in 1914 they purchased a farm in northern Clearwater County and moved there with six children.

1.2

The author’s maternal grandparents, Olaf and Hilda Hanson, in front of their barn in northern Minnesota in the 1940s. The farm and barn were a fascinating place to visit and discover.

The author’s maternal grandparents, Olaf and Hilda Hanson, in front of their barn in northern Minnesota in the 1940s. The farm and barn were a fascinating place to visit and discover.

My father’s mother, Synevva Eri, emigrated from Norway in 1903 and joined an older brother, Nils Eri, on his homestead farm in North Dakota. Several years later she met and married my immigrant German grandfather, George Thorbecke, who died in the great flu epidemic of 1918. After his death she moved with six children, including my father David who was the oldest, from her farm in North Dakota to be near another older brother, David Eri, who had a homestead farm near Gonvick in Clearwater County in Minnesota.

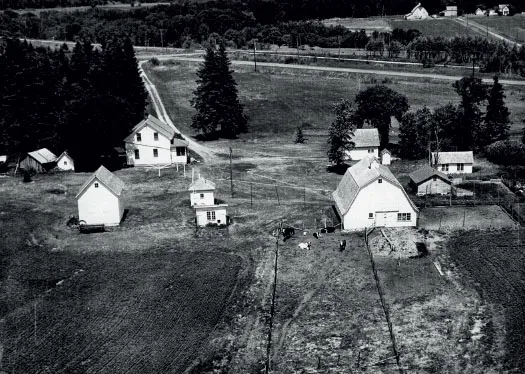

Shortly after arriving in Minnesota she purchased a farm across the highway from her brother and the story goes that she hired a neighboring Norwegian bachelor farmer, Oscar Graftaas, to build her a barn – and he never left because they soon got married! Big Oscar, as we called him, was my step-grandfather who could not read or write, yet the barn he constructed in the 1920s is as straight and true today as it was when he built it. Synevva had two more children with Big Oscar and with her strong and sparkling personality she was an inspiration to all of her seventeen grandchildren. The farmstead with house, barn, and out-buildings is very typical of the cluster of buildings seen in the rural landscape throughout Midwest America (Figure 1.3).

My father drove a gasoline delivery truck to farms in the Gonvick area. One day he made a delivery to the Hanson farm and for the first time saw my mother perched on top of a haystack piling up fresh hay, and the story is that he was immediately smitten and fell in love with her! They married soon after and moved to Bagley, where my father became the owner of a gasoline station and also a grain farm outside of town. From the time I was tall enough to wash windshields I started pumping gasoline and drove a tractor working the grain fields on the farm through high school until I started college.

1.3

Aerial view in 1954 of the farm of the author’s paternal grandmother, Synevva Eri, which was published in the local newspaper.

Aerial view in 1954 of the farm of the author’s paternal grandmother, Synevva Eri, which was published in the local newspaper.

It was on my grandparents’ farmsteads that as a boy I first experienced the uniqueness of a barn and its wooden construction and size, its mystery, the power of light as it streamed into the dimness through small windows and cracks in the siding, and the high arching roof structure of the hay loft. Here I first smelled farm animals, learned what they ate, milked cows and cranked a milk separator, helped harness horses, shoveled manure, climbed to the hayloft and jumped into the hay. On those farmsteads I first handled a team of horses, drove a tractor, helped collect hay in the field and pile it up in haystacks, load hay from wagons into the hay loft of the barn, and tinkered with machinery and woodworking tools. It was a place where people, animals, buildings, machinery, and nature all work together – and it was a marvelous place to experience.

I always liked to draw and thought I would become an aeronautical engineer when I started college; however I soon learned that it was more about fluid dynamics than airplane design as I imagined it. I was taking a course in engineering drafting and expressed frustration to my college professor, Burton Fosse, who invited me to visit an architect’s office with him. When I saw drawings of propo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword by Thomas Fisher

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Rural architectural heritage

- 3 Rural architecture and rural design

- 4 Architecture and agriculture case studies

- 5 Worker and animal safety and health

- 6 Rural sustainability and green design

- 7 In-between landscapes

- 8 Rural futures

- 9 Epilogue

- References

- Illustration credits

- Index